Over the past year, the Municipal Archives has been busy working on the photograph collection of the Mayor David N. Dinkins administration that will be available on our digital platform, Preservica. As the archivist leading this project, I’ve been processing and digitizing both black-and-white and color 35mm photographic negatives and photographic prints. Shooting and scanning various mediums is standard practice and at this point, almost second nature. However, this particular collection is unique in the sense that I am also processing while simultaneously digitizing.

Mayor David N. Dinkins speaks at ribbon cutting ceremony for new low income HPD [Housing Preservation and Development] Housing Cooperative Apartments, March 3, 1992. Joan Vitale Strong, photographer. Mayor Dinkins Photograph Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

Contrary to typical archival workflows in which records are digitized after a collection has been processed, this project combines multiple roles into one: creating an inventory, rehousing material, shooting and editing images, collecting and remediating metadata, and preparing content for publishing. There are various benefits to this method of archiving that I will describe in more detail below. But first, let’s take a quick look at former Mayor David N. Dinkins.

Headshot of Mayor David N. Dinkins taken at press conference: New Tenant for 7 World Trade Center, March 8, 1990. Joan Vitale Strong, photographer. Mayor Dinkins Photograph Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

David Dinkins was New York City’s first Black mayor, serving in that office from 1990 to 1993. While this in itself is a noteworthy accomplishment, he had a long career in public service and achieved many firsts.

Born on July 10, 1927 in Trenton, New Jersey, Dinkins was one of the first Black members of the United States Marine Corps. He graduated from Howard University and then from Brooklyn Law School. Before his time as mayor, he served in the New York State Assembly and then was appointed as the City Clerk, when, notably, Dinkins transferred the City’s records of New Amsterdam to the Municipal Archives. He then served as the Manhattan Borough President from 1986 to 1989. Dinkins was a founding member of the Black and Puerto Rican Legislative Caucus of New York State, the Council of Black Elected Democrats of New York State, and One Hundred Black Men. He passed away on November 23, 2020.

Press Conference: Mondello Verdict, May 18, 1990. Joan Vitale Strong, photographer. Mayor Dinkins Photograph Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

Mayor David N. Dinkins meets with a group of high school students participating in Operation Understanding, August 2, 1990. Joan Vitale Strong, photographer. Mayor Dinkins Photograph Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

Some of David Dinkins’ most notable policies include changing the composition of the Civilian Complaint Review Board (CCRB) to be fully independent of the NYPD (which contributed to a Police Benevolent Association-backed riot of 4,000 off-duty cops on September 16, 1992), obtaining funding to increase the size of the NYPD and begin the decades-long reduction in crime rates, signing a long-term lease with the United States Tennis Association National Tennis Center to host the U.S. Open (one of the city’s top revenue sources), revitalizing neglected housing in Harlem, South Bronx, and Brooklyn, and creating a housing program for New Yorkers experiencing houselessness. Many identify Dinkins’ controversial response to the 1991 Crown Heights Uprisings as a primary reason for his reelection defeat by former Mayor Rudy Giuliani.

Mayor David N. Dinkins speaks at 17th Annual Foster Grandparents Recognition Program with Mrs. Joyce Dinkins, May 31, 1990. Joan Vitale Strong, photographer. Mayor Dinkins Photograph Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

Mayor David N. Dinkins speaks at Bill Signing Ceremony with Governor Mario M. Cuomo, Battery Park, May 22, 1990. Joan Vitale Strong, photographer. Mayor Dinkins Photograph Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

How does the Municipal Archives capture and preserve this particular mayor and time in New York City’s history?

Mayor David N. Dinkins plays Tennis With Jennifer Capriati, August 21, 1990. Joan Vitale Strong, photographer. Mayor Dinkins Photograph Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

Standard archival practice typically involves multiple but distinct steps carried out by different archivists at different times. After a collection is accepted and added into the archives (a process called accession and appraisal), an archivist will process the collection. This involves conducting an inventory of the records, organizing items based on the creator’s original order, and rehousing anything that may need new folders or boxes. When this activity is complete, an archivist will digitize selected images. From there, a digital archivist will remediate all the textual information (metadata like names, dates, and locations), create digital filenames, and upload everything into a preservation software or collections management system for long-term storage.

Mayor David N. Dinkins speaks at groundbreaking ceremony for P.S. [Public School] / I.S. [Intermediate School] 217, The Roosevelt Island School, to be built by The New York City School Construction Authority, April 30, 1990. Joan Vitale Strong, photographer. Mayor Dinkins Photograph Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

Photograph of the Dinkins Collection in the stacks at 31 Chambers Street.

But that is not what we decided to do for this collection. Rather, we chose to combine the aforementioned steps so that one person (yours truly) is performing them all at once, with the guidance and input of colleagues in Digital Programs, Conservation, Collections Management, Reference, and Diversity Equity and Inclusion (DEI). The benefit to this method includes maintaining consistency throughout the entire process so that everything from the camera set-up to the filenames is standardized and ready to go.

Before taking you through my workflow, I’ll shed some light on the scope and content of this soon-to-be-published collection, which contains 139 ½ cubic foot boxes. Each box contains labeled folders filled with photographic negatives, photographic prints, corresponding paperwork, and sometimes (though rarely) ephemera, which all relate to a specific event from the Dinkins administration. Some examples include Dinkins’ swearing-in ceremony, Nelson and Winnie Mandela’s visit to New York City, the Puerto Rican Day Parade, and of course numerous courtesy calls and press conferences.

Mayor David N. Dinkins and Joyce Dinkins at the swearing-in ceremony, January 1, 1990. Joan Vitale Strong, photographer. Mayor Dinkins Photograph Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

Nelson and Winnie Mandela at City Hall, June 20, 1990. Joan Vitale Strong, photographer. Mayor Dinkins Photograph Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

Students and staff at Medgar Evars College greet Nelson and Winnie Mandela, June 20, 1990. Joan Vitale Strong, photographer. Mayor Dinkins Photograph Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

Nelson Mandela takes photograph with boxers Sugar Ray Leonard, Joe Frazier, Mike Tyson; June 22, 1990. Joan Vitale Strong, photographer. Mayor Dinkins Photograph Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

Mayor David N. Dinkins hosts a reception in honor of Asian American business leaders, July 24, 1990. Joan Vitale Strong, photographer. Mayor Dinkins Photograph Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

Mayor David N. Dinkins marches in the Puerto Rican Day Parade, June 10, 1990. Joan Vitale Strong, photographer. Mayor Dinkins Photograph Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

The materials arrived at the archives with some descriptive information attached, which makes processing a whole lot easier than when you have little or no context. We received a spreadsheet inventory filled out by members of Dinkins’ office, identifying events, dates, times, notable persons, locations, and other relevant information about each folder.

What happens between receiving the collection and getting the photographs up and viewable onto our website? Quite a lot actually.

Photograph of an open ½ cubic foot box.

First, I take a quick look at each box (working with five at a time), ensuring the folders are in order by date and time. Some boxes are overstuffed which can damage the materials by bending or warping them. Others are under-stuffed, which can also lead to damage by causing items to fold over themselves. In these instances, I either add or remove folders so that they are snug but not too tight in each box. After this, I update the pre-existing inventory with new folder and box numbers.

Photograph of a negative contact sheet.

Photograph of a negative sleeve.

Photograph of the author shooting a film strip in the darkroom at 31 Chambers Street.

After I have completed processing five boxes, I begin to shoot them using a DT Atom camera, a lightbox, a negative carrier, and Capture One photo-editing software. The negatives come in sleeves with contact sheets attached. Most of the time, someone from the mayor’s office already chose which images to be printed by marking a frame with a red wax pencil. This of course makes my job easier as I simply follow their guidance. However, many times contact sheets are unmarked, so the decision is left to me. This requires a surprising amount of time, as I try to be intentional and thoughtful about which images are important to have online.

To streamline this process, I created a list of criteria. This includes:

Clarity/quality: Is the frame out of focus? Is the negative strip damaged? Are people’s eyes closed? etc.

Content: Frames that show multiple and new people not yet captured.

DEI concerns: Ensuring a wide diversity of individuals captured.

Historical context: Any visible text, signage, architecture, etc.

Format: A combination of candid and portraits/color and black-and-white.

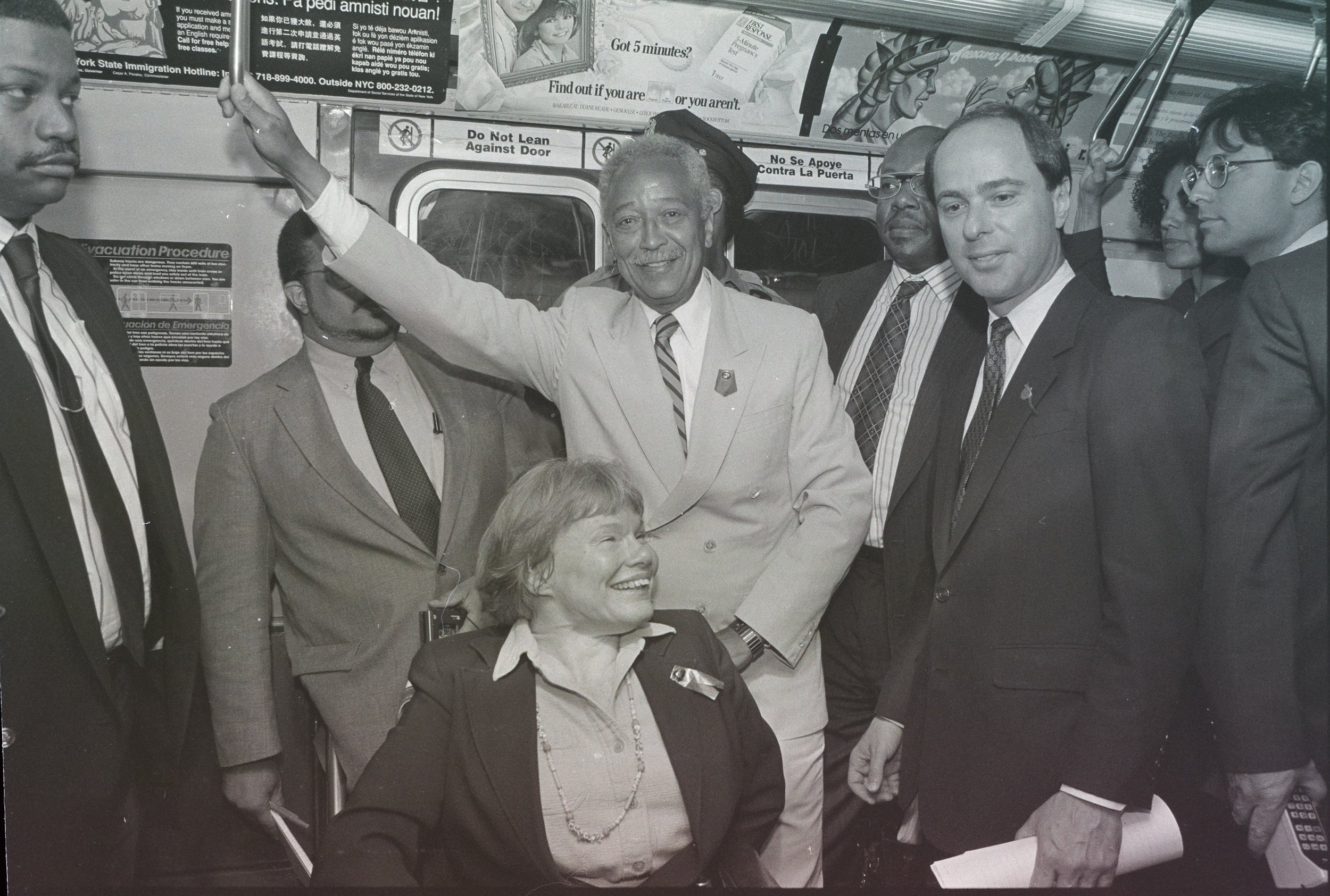

Mayor David N. Dinkins demonstrates the accessibility of the city’s subways for people with disabilities, June 29, 1990. Joan Vitale Strong, photographer. Mayor Dinkins Photograph Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

Aerial view of Manhattan skyline, April 9, 1990. Joan Vitale Strong, photographer. Mayor Dinkins Photograph Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

After shooting each sleeve, I change the image names to the official filenames that will appear on our storage server and in Preservica (a seemingly miniscule yet critical task that ensures the longevity, consistency, and user accessibility of our digital materials). The filenames include information about the collection number, series number, box number, and item number. For example, the filename REC0037_13_001_001_01_01 tells us that the collection is REC0037, that the series is 13 (which identifies that it’s photographs), that the box number is 1, that the negative sheet is 1 (there are usually more than one per folder), and that the frame is 1.

Next, comes editing and exporting the images. The Municipal Archives adheres to the Federal Agencies Digital Guidelines Initiative (FADGI), so editing is fairly basic, as too much can interfere with these standards. Most importantly, I straighten and crop each shot so that there is only one image per frame. Some negatives are damaged by environmental factors like time and improper handling. In these cases, I may adjust levels or exposure to ensure clarity. This is particularly true for color images.

Screenshot of Capture One photo-editing software

After editing, I export the files into TIFF images. TIFFS are the highest resolution files (unlike JPGS or PNGS which are lower resolution) and therefore used for preservation-quality master copies. This only takes several minutes, but moving the files onto our storage server can take up to an hour due to their size and volume.

When the photographs are ready, I begin to enter the metadata from the original inventory as well as additional information I’ve collected into a Dublin Core spreadsheet. Dublin Core is the archival standard that we use for all collections (aside from audiovisual and moving image collections which require unique standards). Dublin Core is used to ensure the format of each information field, like title, date, and location, is consistent and ready for our digital preservation archivists to ingest into Preservica.

Mayor David N. Dinkins accompanies the tenant patrol of the New York Housing Authority’s Brevoort House on its evening rounds, September 24, 1990. Joan Vitale Strong, photographer. Mayor Dinkins Photograph Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

Mayor David N. Dinkins hosts a lawn party in honor of the children of New York City, June 8, 1990. Joan Vitale Strong, photographer. Mayor Dinkins Photograph Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

Announcing the ASCAP [American Society of Composers, Authors, and Publishers] Foundation's Louis Armstrong Fund with Cab Calloway, August 18, 1990. Joan Vitale Strong, photographer. Mayor Dinkins Photograph Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

Although most of the metadata has already been collected by members of the Dinkins Photo staff at the time of creation, some information may need editing. This includes adding the first names of women (who are often described as Mrs. [insert husband’s name]), problematic and archaic terminology (the archives intentionally keeps original language and we contextualize and update wording within [brackets]), spelling out acronyms, and editing grammatical and spelling errors.

There are a lot of people captured in these images whose names are not in the documentation and who we can’t easily identify. To tackle this issue, we have created a pilot project to crowd-source information from members of former Mayor Dinkins administration. Who better to name and describe the individuals featured than the individuals themselves! We will report on this part of the project in a future blog.

Mayor David N. Dinkins testifies before House Subcommittee on bills to expand Medicaid coverage for HIV III [Human Immunodeficiency Virus] and to provide residential drug treatment for pregnant women, September 10, 1990. Joan Vitale Strong, photographer. Mayor Dinkins Photograph Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

There is a lot of behind-the-scenes work required in an archival digitization project. With the overwhelming amount of online media to which many of us are now accustomed, this might be surprising. But, but hopefully this blog can shed light on why “digitizing everything” is simply unrealistic. After all, these projects involve a high cost of labor, time, and funding. All that being said, while this work can be meticulous, repetitive, and invisible, there is definitely fun to be had. Below I’ve included some of my favorite images. We’re still in the beginning part of this project, having digitized 25 boxes with about 120 boxes remaining.

Winnie Mandela and Dinkins at a private luncheon at United States Coast Guard Building, June 20, 1990. Joan Vitale Strong, photographer. Mayor Dinkins Photograph Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

Audience watches Nelson Mandela receive a key to the City Of New York, June 20, 1990. Joan Vitale Strong, photographer. Mayor Dinkins Photograph Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

Mayor David N. Dinkins speaks at a rally of 400 junior and senior high school students, June 18, 1990. Joan Vitale Strong, photographer. Mayor Dinkins Photograph Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

Lawn party in honor of the children of New York City, June 8, 1990. Joan Vitale Strong, photographer. Mayor Dinkins Photograph Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

ASCAP [American Society of Composers, Authors, and Publishers] Foundation's Louis Armstrong Fund with Cab Calloway, August 18, 1990. Joan Vitale Strong, photographer. Mayor Dinkins Photograph Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

Joyce Dinkins hosts a party for children enrolled in New York City's Early Childhood Program with Mickey Mouse, Minnie Mouse and Goofy, July 6, 1990. Joan Vitale Strong, photographer. Mayor Dinkins Photograph Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

Mayor David N. Dinkins greets school children at Bill Signing Ceremony, Battery Park, May 22, 1990. Joan Vitale Strong, photographer. Mayor Dinkins Photograph Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

David and Joyce Dinkins at the private swearing in, January 1, 1990. Joan Vitale Strong, photographer. Mayor Dinkins Photograph Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.