ON THE JOB, archivists come across many interesting items that they wish they could share with the world. In this series, Stumbled Upon, we share some of those items with you.

The Tough Club

Invitation to the annual ball of the Tough Club, 1890. Mayor Hugh J. Grant subject files, NYC Municipal Archives.

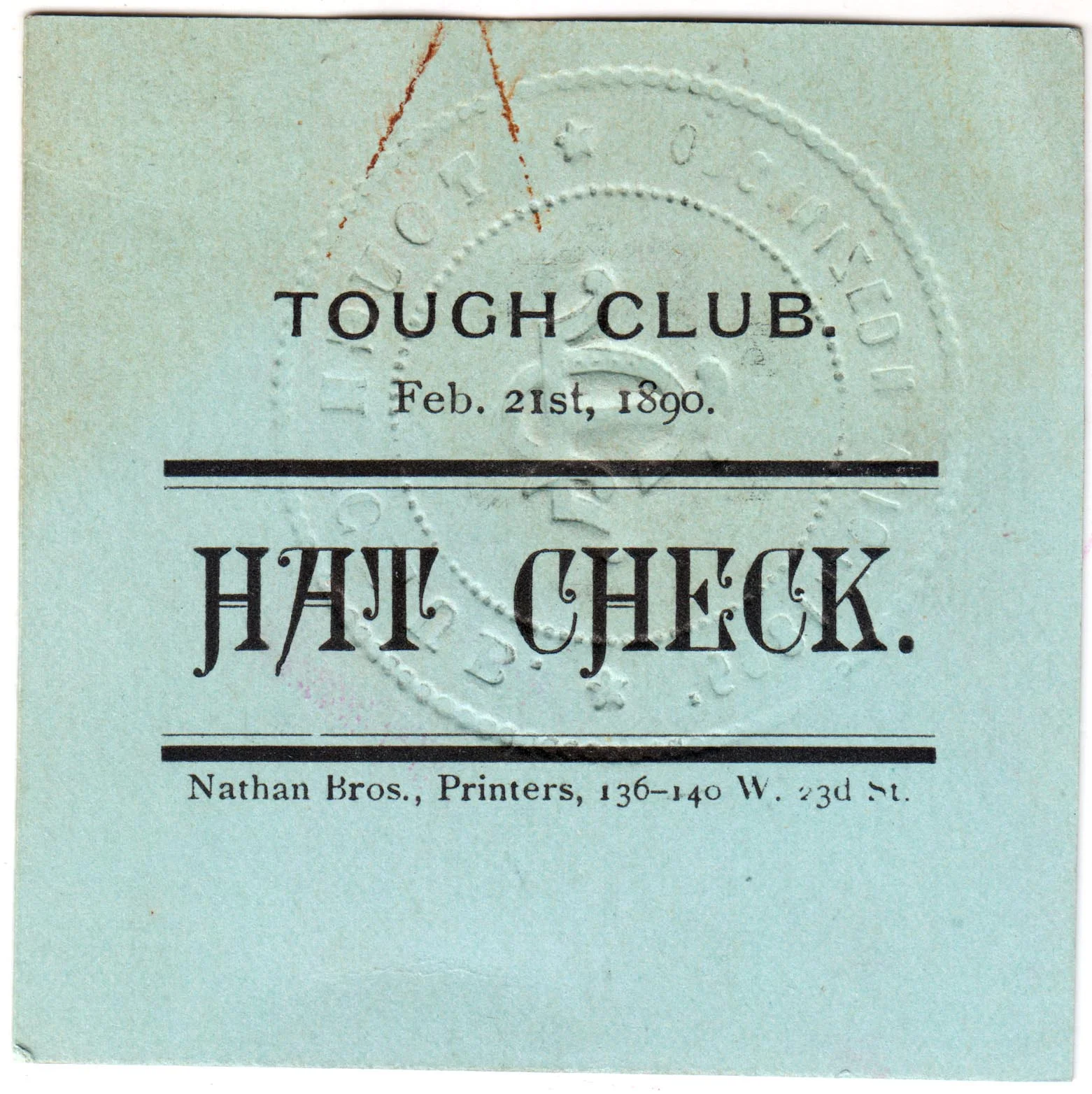

Tough Club hat check tag, 1890. Mayor Hugh J. Grant subject files, NYC Municipal Archives.

During the latter half of the 19th century, social clubs became wildly popular among the gentlemen of New York. The Mayor of New York would have been a sought-after member for any one of these clubs, as they also often served as a political hangout. Mayor Hugh J. Grant received this invitation to a ball held by the Tough Club in 1890. Their name alone sparks curiosity. One would assume members of the Tough Club, which was established in 1865, would have taken after its namesake, however, a New York Times article from January 18, 1893 dashes that notion: “If a gentleman, or one whom you have always regarded as a gentleman, were to remark to you that he was a “Tough,” you would be excused if you looked at him in amazement and silently meditated on the possibility of his insanity. Yet the Tough Club is an organization of gentlemen of the Ninth Ward” – also known as Greenwich Village – “who are tough only in their determination to do right and stand by each other and their friends, and do it manfully.”

Today there isn’t much of a trace of the Tough Club, whose headquarters at 243 West 14th Street allegedly served as a speakeasy during Prohibition. The building has been occupied by food and beverage businesses since the early 2000s.

The original Steinway Hall

Diagram of the layout of Steinway Hall, undated. Mayor Hugh J. Grant subject files, NYC Municipal Archives.

Steinway Hall was the first concert hall built by piano-makers Steinway and Sons, located at 71-73 East 14th Street, behind their elegant showrooms. The hall’s cornerstone was laid by William Steinway on May 22, 1866. The image above depicts the layout of the 2,500 seat concert hall, situated on the first floor with balcony seating. The building was four stories high, and included space for a 100 piano showroom and practice rooms. Over 700 gaslights illuminated the instantly-popular Steinway Hall, which was the home of the New York Philharmonic Orchestra for 25 years (from 1866 to 1891) and hosted readings by Charles Dickens. The concert hall remained at this location until the building was sold in 1923 and Steinway Hall was moved uptown.

Ticket for concert at Steinway Hall, 1890. Mayor Hugh J. Grant subject files, NYC Municipal Archives.

Letter from William Steinway to Mayor Grant, 1890. Mayor Hugh J. Grant subject files, NYC Municipal Archives.

Grave Marker of the Matinecoc Native Americans

Boulder split in half with carving "Matinecoc" and plaque reading "Here Rest the Last of the Matinecoc Indians Erected by the Major Thomas Wickes Chapter Daughters of the American Revolution-1948." Photo taken at Zion Church Yard, Douglaston, Queens, 1955. Borough President Queens collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

It’s hard to imagine a New York City that isn’t overwhelmed with people and infrastructure, but in the centuries before Europeans began settling on the land in the 1600s, Native Americans made up the entire population. Unfortunately, today there is little evidence to serve as a reminder of their presence, and what we do have is often overlooked or forgotten.

Zion Cemetery on Northern Boulevard in Douglaston, Queens, 1926. View west from cemetery at church entrance. Borough President Queens collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

An unsettling example of this resides at the Zion Episcopal Church in the northern Queens neighborhood of Douglaston, a section of New York that is actually known for its peaceful quaintness. The Munsee-speaking Matinecoc, loosely-related to the Lenape, were one of the Native American groups that settled the land; the original “Long Islanders,” if you will. Their territory stretched across a series of inlets on the northwest side of the island, including a section of Little Neck Bay, where Douglaston is located. By the 1640s, English and Dutch colonial towns had begun to be established in northeastern Queens, growing westward. In 1656, a Dutchman, Thomas Hicks, was given a peninsula named “Little Madnan’s Neck”; the peninsula included most of Douglaston within its boundaries. Hicks evicted the Matinecoc from their remaining property on Little Neck Bay in 1656, during what came to be known as the “Battle of Madnan’s Neck,” on today’s intersection of Northern Boulevard and Marathon Parkway. It is the only documented seizure of property in Flushing town records and drove the last remaining Matinecoc from Douglaston and Little Neck.

The Matinecoc were virtually erased from Long Island history until the 1930s, when, to add insult to injury, a Matinecoc burial ground between 251st and 252nd Streets was literally crashed into when construction crews were widening Northern Boulevard. This burial ground was known and appeared on Queens topographical maps of that time, but the need to widen the road trumped the placement of the burial ground, despite protests led by James Waters, Chief Wild Pigeon of the Long Island Native American community. In October 1931, the graves, totaling of about 30, were reinterred in the cemetery of Zion Episcopal Church. The mass grave is marked by a boulder split in two by an Oak tree that reads, “Here Rest the Last of the Matinecoc.” [Note: There are still Matinecoc descendants in the area.] A second memorial was erected in front of the boulder in 1948 by the Major Thomas Wickes Chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution.

Further Reading

Claudia Gryvatz Copquin, The Neighborhoods of Queens. Yale University Press, 2009.

Kelly Crow, “Neighborhood Report: Chelsea; Tough Club, a Dashing Man, And His Invisible Footprints,” The New York Times, August 25, 2002. http://www.nytimes.com/2002/08/25/nyregion/neighborhood-report-chelsea-tough-club-dashing-man-his-invisible-footprints.html

“Curiosities in Clubs,” The New York Times, January 15, 1893. http://query.nytimes.com/mem/archive-free/pdf?res=9507E3DE1731E033A25756C1A9679C94629ED7CF

“Douglaston Hill Historic District Designation Report,” New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission, December 14, 2004. http://www.nyc.gov/html/lpc/downloads/pdf/reports/dhill.pdf

Kenneth T. Jackson, ed., The Encyclopedia of New York City. Yale University Press, 1995.

“DLNHS Newsletter,” Douglaston and Little Neck Historical Society, Spring 2009. http://www.dlnhs.org/newsletter/Newsletter_0905.pdf

T.M. Rives, Secret New York – An Unusual Guide: Local Guides by Local People. Jonglez Publishing, 2012.