For the Record has featured research and records about Markets in several articles including the Unbuilt 8th Ward Market in Brooklyn, the Fulton Fish Market strike, and the WPA manuscript on the fish market. The Bronx Terminal Market makes an appearance in the artichoke wars, but we have never covered the rich history of New York City’s public markets.

Supplying a diverse and teeming city with fresh food has been a constant problem in New York. Farmers’ Markets, which have undergone a resurgence in recent years, are nothing new. In the early days of New Amsterdam, farmers and Native Americans simply brought their crops to town and set about hawking them, usually along the bank of the East River, known as the Strand. While references exist as early as 1648 to “market days” and an annual harvest “Free Market,” the process was unregulated and inefficient. Peter Stuyvesant, the Director General and the Council recognized this and decreed: “Whereas now and then the people from the country bring various wares, such as meat, bacon, butter, cheese, turnips, roots, straw, and other products of the farm to this City for sale, arrived with which at the strand they must often remain there with their goods for a long time to their great damage... Therefore, the Director General and Council hereby order, that henceforth Saturday shall be held and kept as Market Day in this City on the Strand near the home of Master Hans Kierstede... September 12, 1656.”

In his 20th Century redrafting of the 1660 Castello plan of New Amsterdam, James Wolcott Adams added a line of vendors next to the fort and a small building representing the butcher stalls called the “Broadway Shambles.” The earliest market was held at the corner to the left of the docks at what is now Pearl and Whitehall Streets. I.N. Phelps Stokes, The Iconography of Manhattan Island, 1498-1909.

This first market was located at the corner of what are now Pearl Street and Whitehall Streets, but within two years, it was moved up the street to an open area next to the fort. The first mention in the Records of New Amsterdam of this location is on February 9, 1658, when it is referred to as the Marcktvelt or Marketfield. Some historians locate this at the site of today’s Bowling Green while I.N. Phelps Stokes, probably more correctly, places it east of the fort on Whitehall Street. A small alleyway near there still bears the name Marketfield Street, the path the merchants would take to the Market after coming up Broad Street from the docks.

A year later, in January 1659, the Dutch established “a market for lean and fat cattle, oxen, cows, sheep, goats, pigs, buck and the like...” Lean cattle could only be sold during the month of May, and fat cattle could be sold from October 20th to November 30th. By April 1659, further details of the market emerged, and it was resolved “to erect a meat market and cover it with tiles, to have a block brought therein, and to leave the key with Andries the baker, who shall have temporary charge thereof.” These early 1659 records are missing from the Municipal Archives holdings, but D.T. Valentine, Clerk of the City and perhaps its first Archivist, quotes them in a history of the public markets for his 1862 Manual of the Corporation Council. No mention of the exact location of this market is in the ordinance, but it was likely at the southern end of the Marketfield next to the fort. Staffed by 12 butchers given authority to slaughter animals within city limits, it was the first permanent market building in New Amsterdam. Valentine continues, “It was further resolved, that ‘the market for live cattle shall be beside the churchyard where some stakes shall be fixed.’” Valentine identifies this as the west side of Broadway above Morris Street.

The Maerschalck Plan of New York in 1754 shows the location of markets in the English Colonial Era: The Broad Street or Exchange (7), the Fish (8), the Old Slip (9), the Meal (10), the Fly (11), the Burlins (12), and the Oswego (11). Map courtesy The Library of Congress.

In 1677, the English Governor Edmund Andros established a second market house at “the Water Side neare the Bridge and weighhouse [the Bridge was the pier built by the English to encircle the docks]” to be open every Saturday for three years. The same resolution also established a country fair “att Breucklin [Brooklyn] for Cattel Graine & Produce of the Country” on the first Monday, Tuesday and Wednesday in November. After the three-year term expired on the market house the market day was changed to Wednesday, and in 1683 the English established three market days, Tuesday, Thursday, and Saturday. The Customs House Market, as it became known, lasted until 1684 when it was moved “to the Vacant ground before the Fort,” the site of the Marketfield.

View in New York, 1746 (Lower Market). Valentine’s Manual for 1858. NYC Municipal Library

Starting in 1691, the Common Council established several new sites for markets that were built over the next decades: The Broad Street Market (the recently filled in Dutch canal made for a wide open area), the Fish Market (also known as the Lower Market, or Coenties Market at Coenties Slip), the Old Slip Market (also known by the less endearing name “The Great Flesh Market”), the Fly Market or Upper Market at Pearl Street and Maiden Lane (the name Fly originated from its location on the lower end of Smith Street that ran to the water known as Smith’s Vly or Valley, but over time Vly transformed into Fly), and the Meal Market at Wall and Pearl Streets for the sale of corn, grain, or meal. The creation of new markets would generally occur after neighborhood residents petitioned for a market and contributed funds for the building. Once approved, vendors would pay rent to the city. After a lease term the building would eventually revert to the City which saved the City considerable expense in constructing new markets. The Common Council Papers at the Municipal Archives hold several of these petitions for and against new markets.

Petition for “a market place at the slip at the lower end of Dey Street in the west ward…” March 15, 1763. Common Council Papers, NYC Municipal Archives. Although this petition does not seem to have been granted, the Bear Market was built on the western end of Vesey Street a few year later.

In 1711 the Common Council also designated the Meal Market as the City’s first slave market when they passed a law “that all Negro and Indian slaves that are let out to hire… be hired at the Market house at the Wall Street Slip…” This market was destroyed in 1762, and for a time the Fly Market also functioned as a slave market.

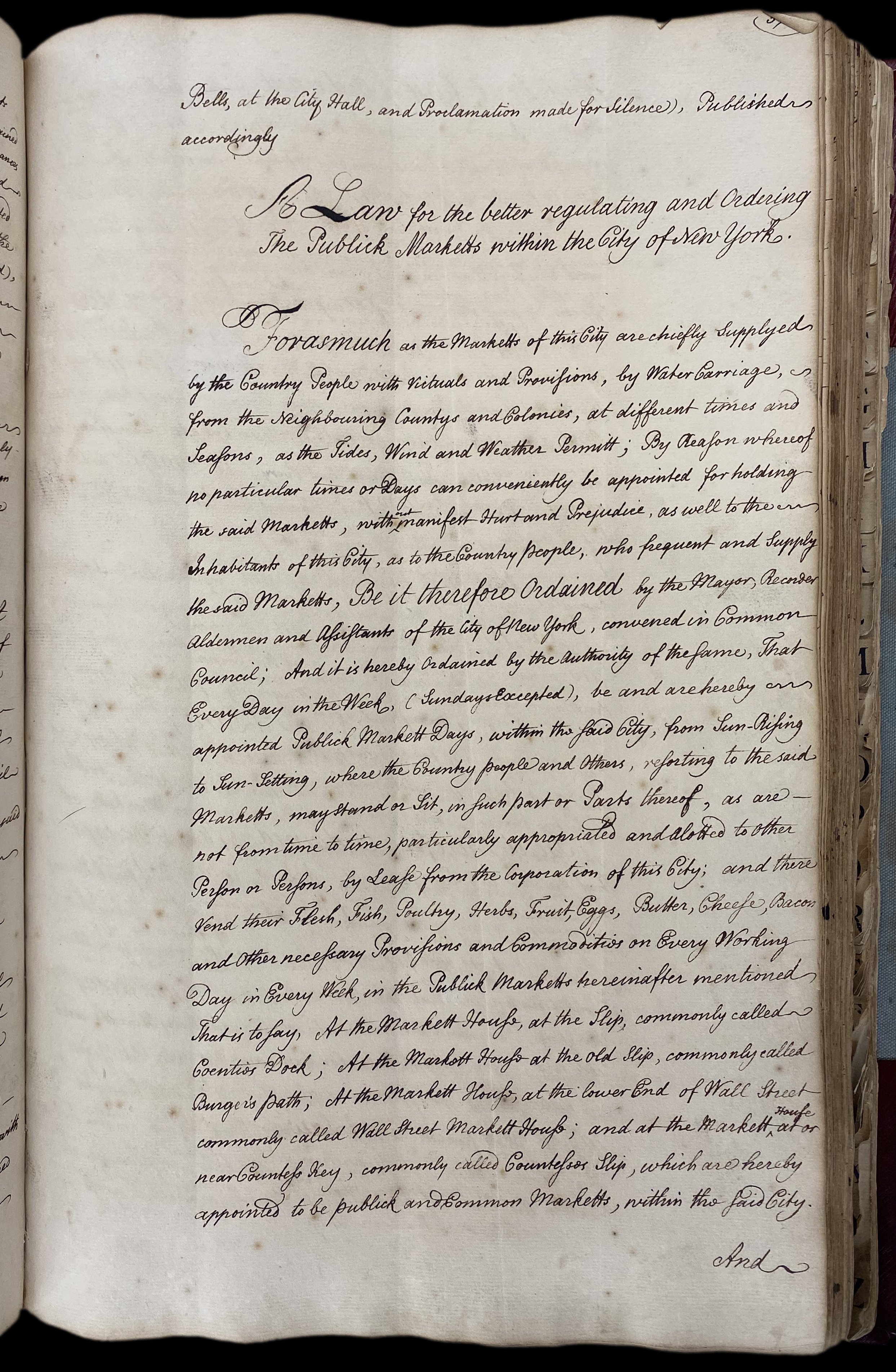

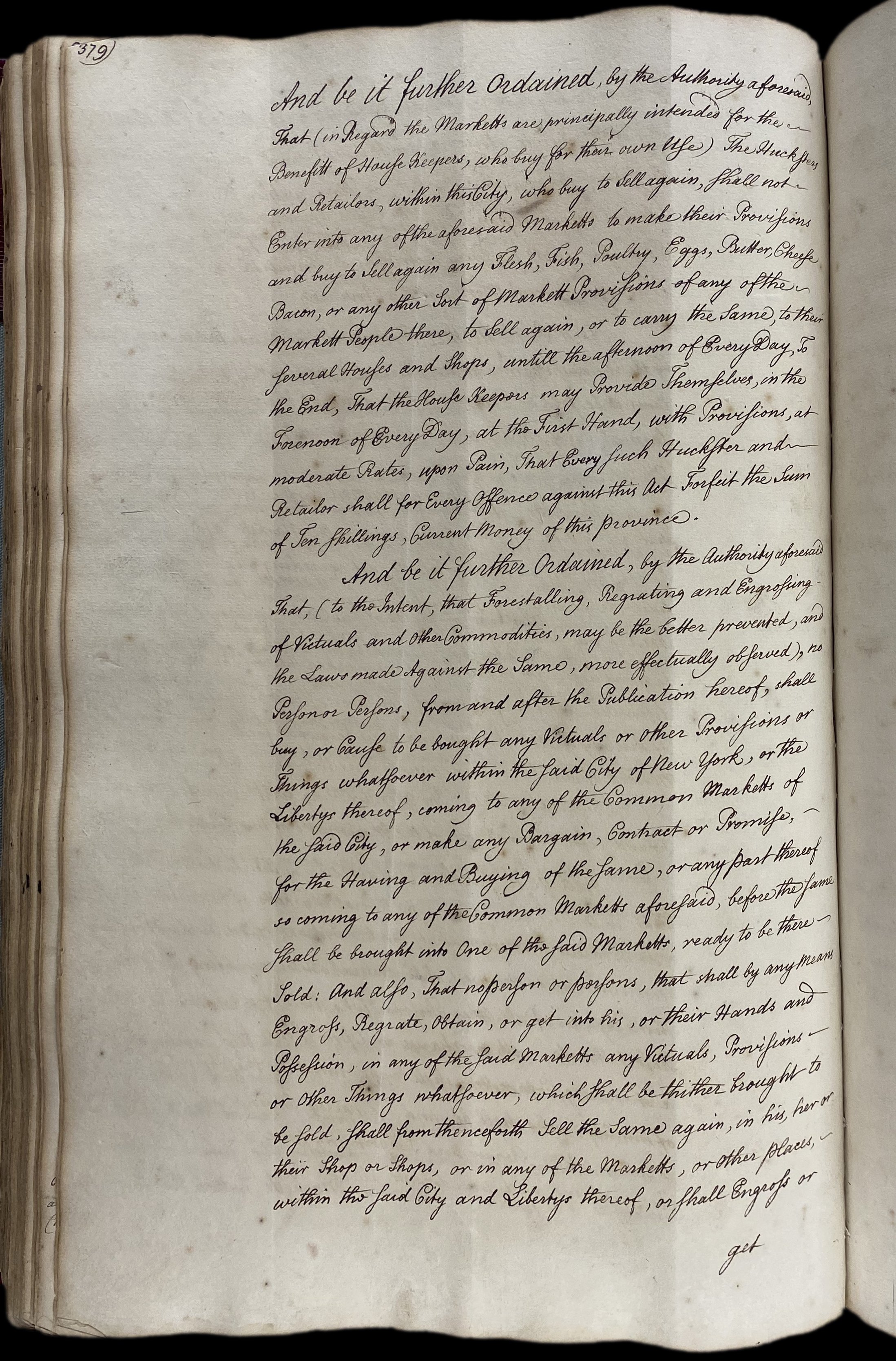

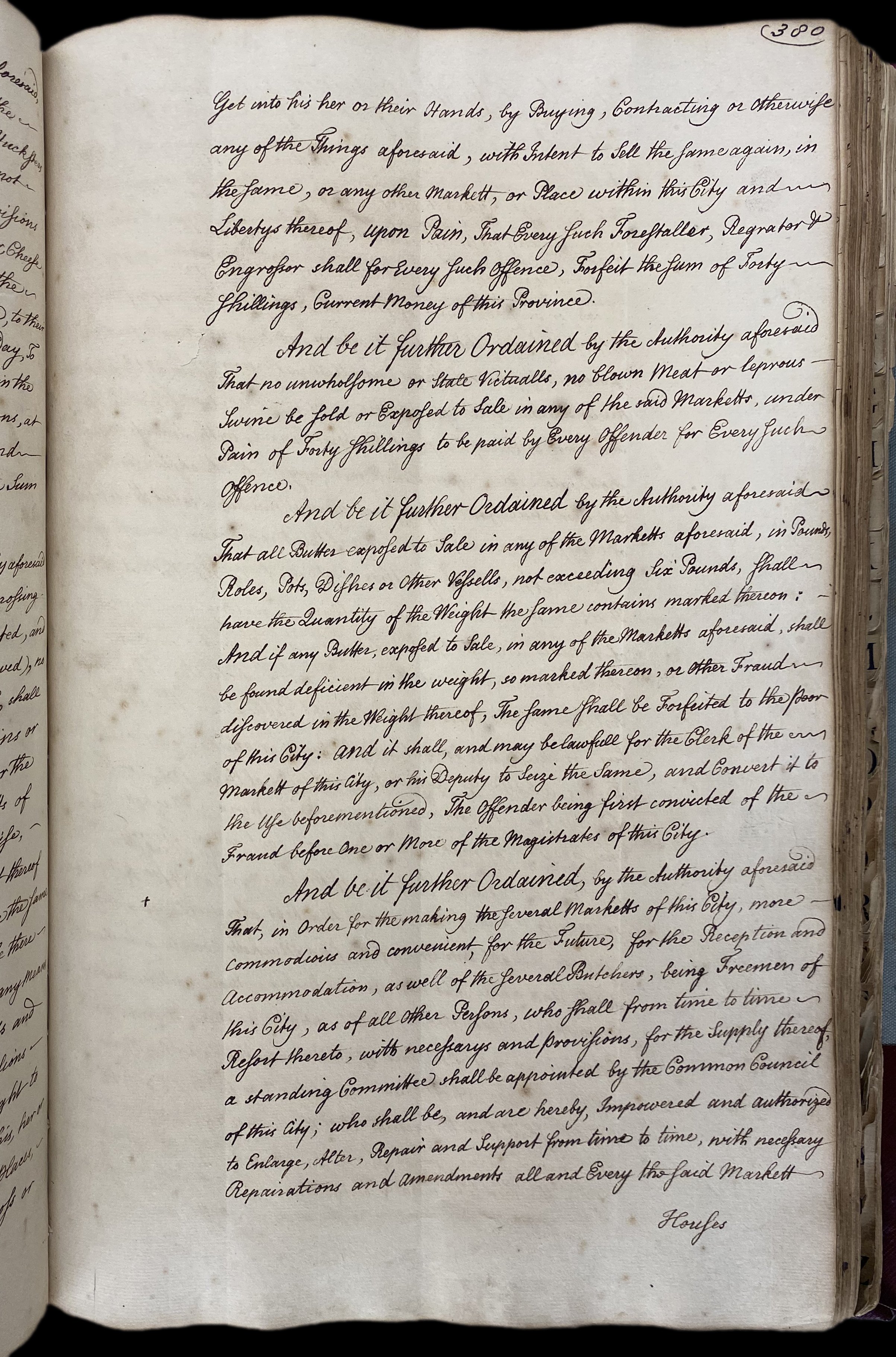

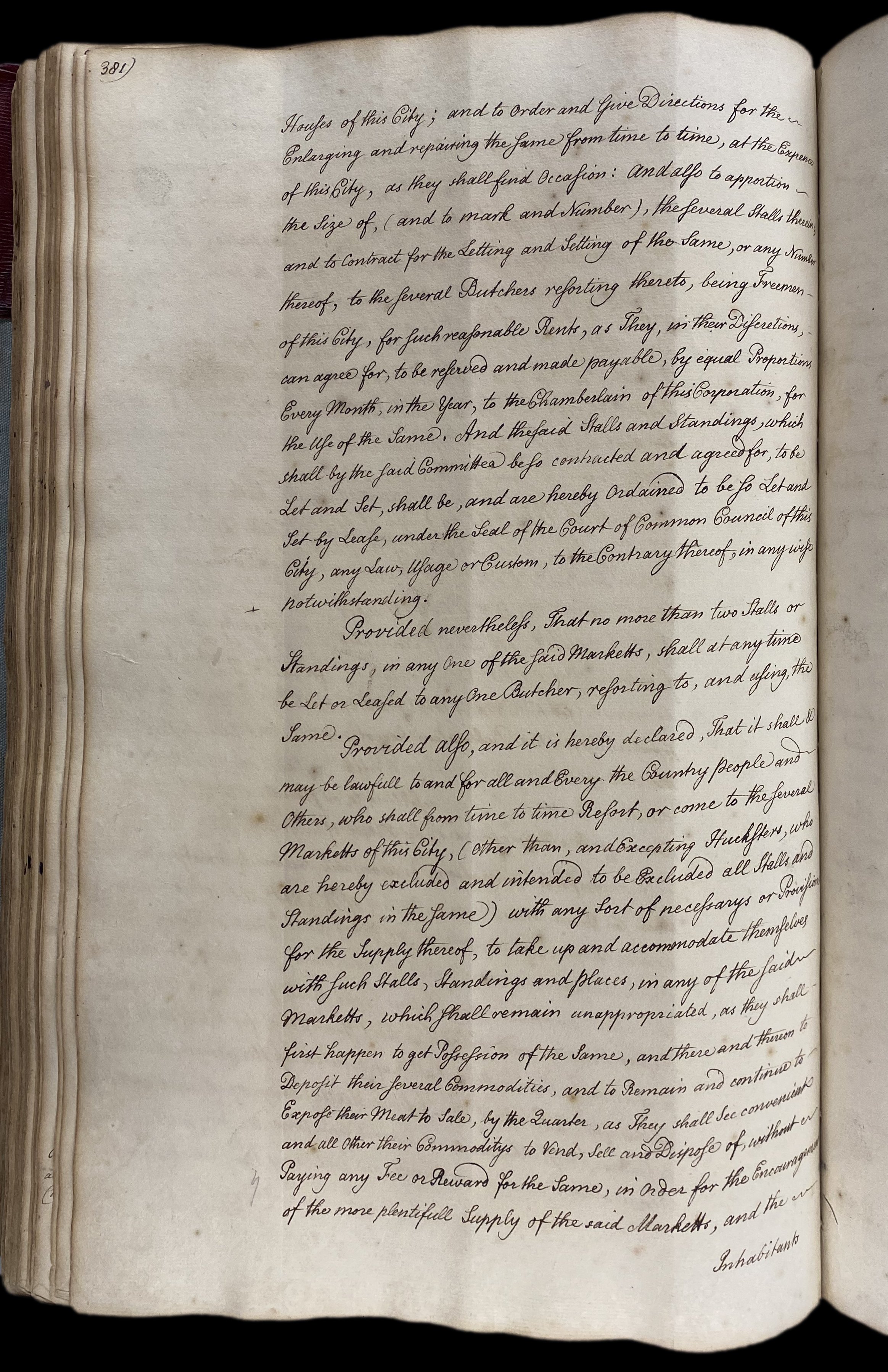

In 1735 the Council issued the first comprehensive system for governing public markets and established a Standing Committee of the Common Council to oversee markets. The Council also recognized the complications caused by so many country people, subject to the vagaries of weather and tides, attempting to reach the city on market days and declared that every day of the week except Sunday would be market days.

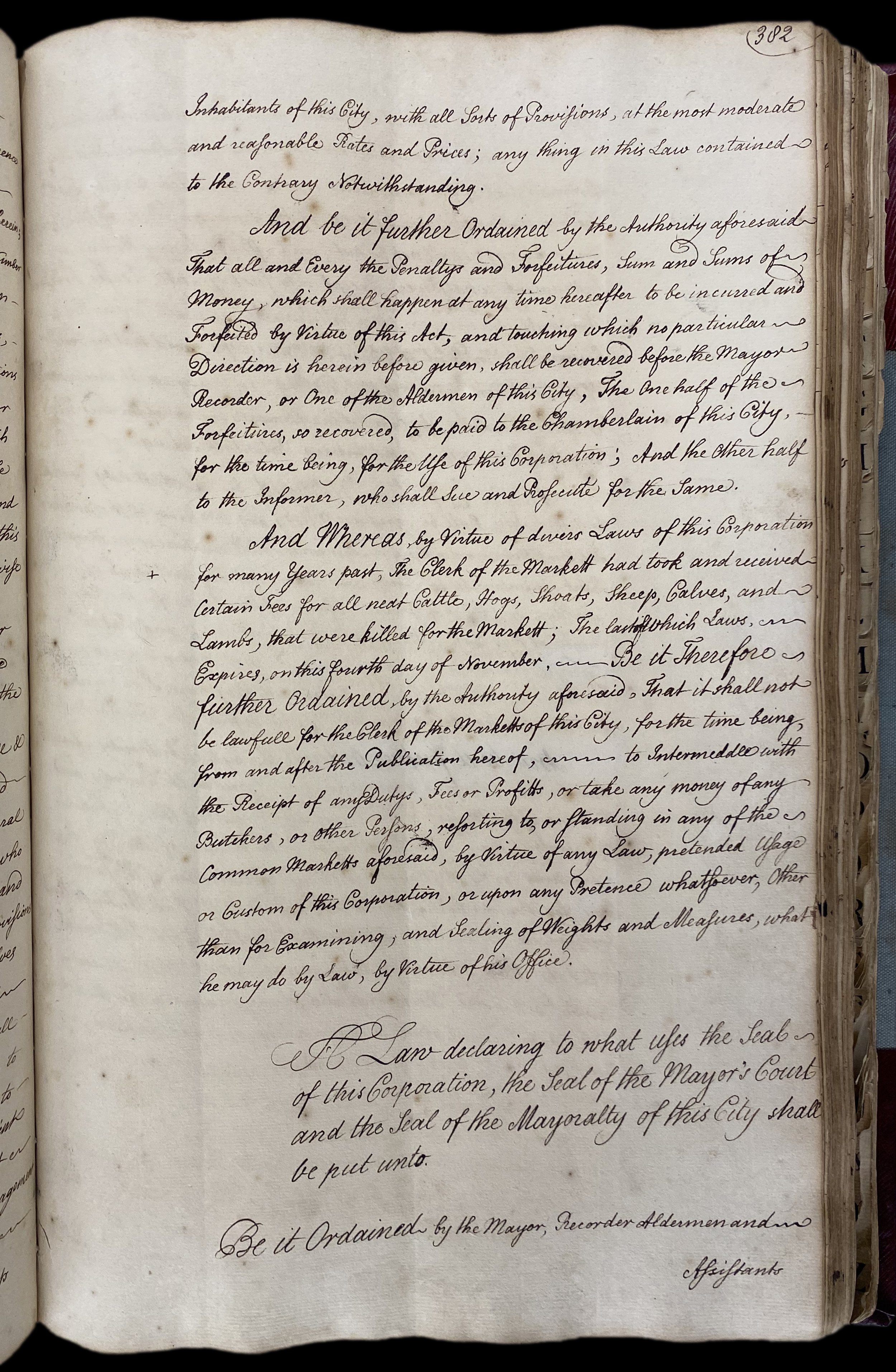

“A law for the better regulating and ordering the Publick Marketts within the City of New York,” March 1735. Common Council records, NYC Municipal Archives. This 1735 law was the first comprehensive list of rules for the public markets.

Since the Dutch times there had been committees or clerks to oversee markets, to ensure fair measures and weights, and to administer licenses. Forestallers, those who would buy goods before they came to the market stall, often would attempt to corner a market and drive up prices. Regulation of the markets was an ongoing and ever-evolving problem, but the rules were often unfair or outright racist. Answering the petition of one Saul Browne in 1685, the Council’s opinion, “was, that noe Jew ought to sell by retail within the city; but may by wholesale, if the Governour think fit to permit the same.” And in 1686 the council renewed a prohibition to trade with Native Americans. In 1740, an ordinance forbade trading between Native Americans and enslaved persons at the Oswego Market “for promoting disease.” In 1781, Samuel Birch, British Commandant of New York during the revolution, laid out ten market regulations. Amongst the usual rules regarding times and places, he forbade “no negro, or other slave living in town, shall be permitted to buy or sell victuals, or provisions of any kind, for the use of his or her master or employer, without a ticket in writing for that purpose…. Nor… sell produce of their plantations in the said markets, without such a license or authority.…” Ephraim Smith, clerk of the market, was charged with examining “the weights and measures made use of in said markets….”

Market account for February 1788 to January 1789. Common Council Papers, NYC Municipal Archives.

In 1738, the inhabitants of the West Ward complained of being far from the markets and in need of a market accessible to the Hudson River for the country people from New Jersey and upstate. The result was a market house 42 feet in length and 25 feet wide in the middle of Broadway at Crown Street (renamed Liberty after the Revolution). The Exchange Market on Broad Street was also added at this time and the Peck Slip market was added in 1763.

This 1767 map also made special note of the markets: The Exchange Market (25), the Fish Market (27), the Fly Market (28), the Old Slip Market (29), the Peck Slip Market (30), and the Oswego or Crown Market (31). The Meal Market on Wall Street, which became a slave market in 1711, was destroyed in 1762 before the time of this map as was the Burlins Market. Market Plan of the City of New York, Surveyed in 1767. George Hayward for Valentine’s Manual of 1854. NYC Municipal Library.

The Crown Market or Oswego Market on Broadway was expanded in 1746 by another 21 feet and started to become an impediment to travel. In 1771, it was declared a nuisance, and it was resolved to build a new market on the west side and a smaller Oswego Market on Maiden Lane east of Broadway. The Fish Market, the Old Slip Market, and the Crown were all gone during or soon after the American Revolution, but the late 18th Century also saw the establishment of additional markets, including the Bear or Hudson Market on Vesey Street, the Catherine, and the Spring Street Markets.

Fly Market from the corner of Front Street and Maiden Lane, N.Y. 1816. George Hayward for Valentine’s Manual for 1857. NYC Municipal Library. Licensed butchers and vendors had stalls in the market building, country peddlers or “hucksters” set up unlicensed tables in the area.

The markets were becoming centers of public life and civic pride and these later 18th Century markets were often built with bell or watch towers as centerpieces. The bells were rung to open and close the market days and sales after the closing bell were strictly forbidden. In 1783 the outgoing (loyalist) clerk of the markets, Ephraim Smith, “determined that the DAMNED REBELS… should not enjoy so small a convenience… cut down and carried to his house the bell of the Fly Market…” He was ordered to restore the bell to its former place. The council also complained in 1784 of the “Ruinous Condition” of the markets “on the Evacuation of this City by the British Troops.”

By 1789, the Oswego Market was moved off Broadway, the Bear (or Hudson) Market was added at Vesey and Greenwich Streets, and the Catherine Slip Market was under construction. Plan of the City of New York. From the Original Copy Published 1789. George Hayward for Valentine’s Manual of 1857.

The Catharine Market was the first market built after the revolution and the last market built in the 18th Century. It was established in 1786 after a petition by prominent residents including Henry Rutgers to use the recently filled-in Catharine Slip (named after his mother). A humble market at first for butchers and country farmers, a fish market was added in 1797. It would soon become one of the grandest markets in the city.

But we must leave you here and we will pick up the story of the 19th Century markets of New York in Part II.

Sources:

The Records of New Amsterdam, NYC Municipal Archives

The Minutes of the Common Council of the City of New York, 1675-1776

The Minutes of the Common Council of the City of New York, 1684-1831

Thomas F. De Voe, The Market Book, Vol. 1, 1862.

I.N. Phelps Stokes, The Iconography of Manhattan Island, 1498-1909

D.T. Valentine, Manual of the Corporation Council of New York, esp. years 1862 and 1863.