Dog owners in New York City will be familiar with the process of registering and licensing their pets. The Department of Health requires owners to pay a fee and fill out a form that includes the dog’s name, breed, gender, color, and vaccination and spaying/neutering status. This has been standard procedure for well over a century: the first dog licensing law in New York State was passed in 1894. The Municipal Archives collections are notably diverse and comprehensive so it should come as no surprise that dog licensing records can be found in its holdings.

Old Town Records Collection* NYC Municipal Archives.

The place to look is the Old Town records collection. With a grant from the National Historical Publications and Records Commission (NHPRC), the Municipal Archives has been processing the collection during this past year. It is comprised of records created in the villages and towns that were eventually consolidated into the Greater City of New York in 1898. They date back to the 1600s and consist of deeds, minutes from town boards and meetings, court records, tax records, license books, enumerations of enslaved people, school district records, city charters, information on the building of sewers and streets and other infrastructure.

The collection provides documents that are crucial to understanding when the towns and villages were purchased—or sometimes wrested—from the indigenous inhabitants, how the land was divided and sold, who governed the communities, and essentially, a fascinating record of daily life in the communities that made up what became the five boroughs of New York City after 1898.

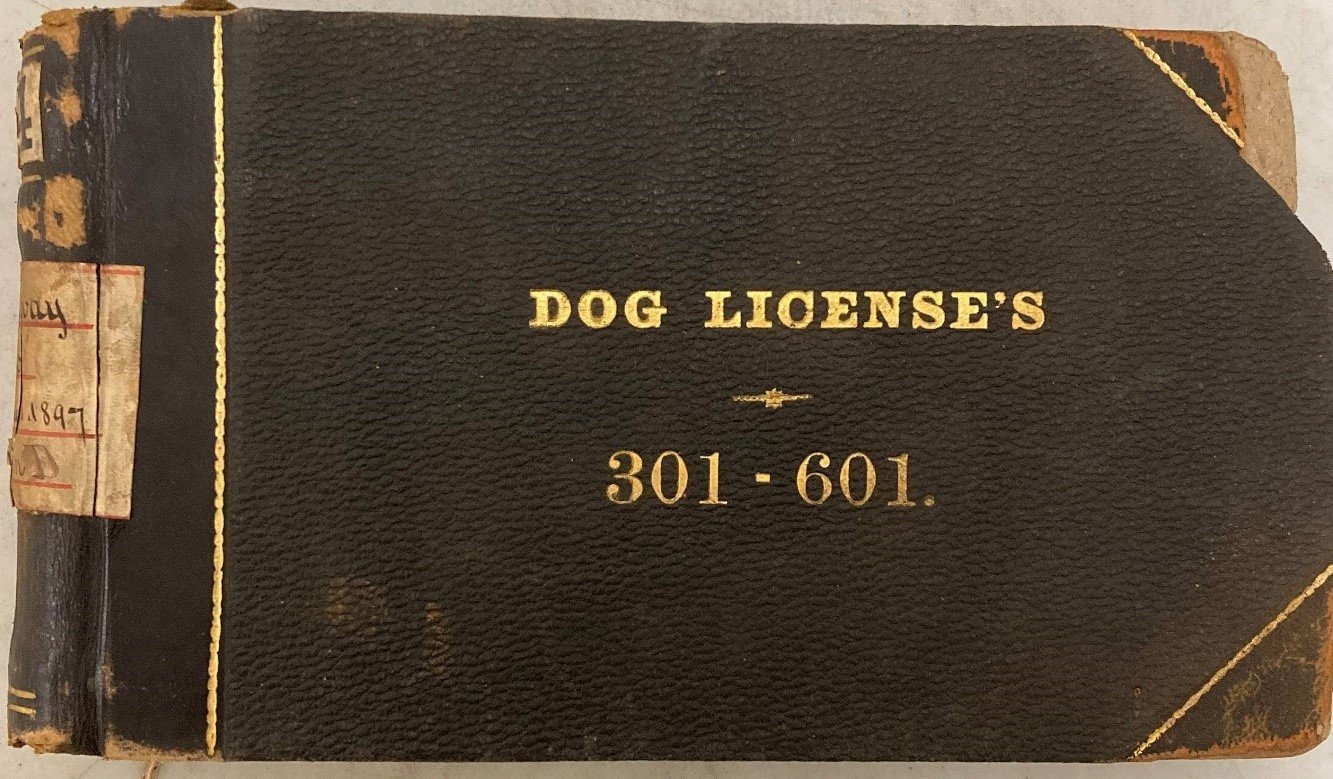

For the Record recently highlighted the collection and the processing project. It described records from the Board of Health, pertaining to slavery in the villages, records about taxes and school districts and town meetings and basic infrastructure and court proceedings. The Old Town collection also contains eleven ledgers related to dog licensing, all from towns and villages in Queens County.

Old Town Records Collection* NYC Municipal Archives.

Old Town Records Collection* NYC Municipal Archives.

While these ledgers provide documentation of an important function of the Board of Health and the history of this practice, it is also simply fun to look through the license books and see what kinds of dogs past inhabitants of the city owned—and what they named them.

Old Town Records Collection* NYC Municipal Archives.

The dog license ledger from the Village of Far Rockaway, dated 1896 to 1897, only a couple of years after the state law was passed, shows how the information required to register a dog with the government remains largely unchanged. Just as it does today, the registration asks for the owner’s name and the dog’s breed, description, and name. The price for registering seems to range between $1 and $2 per year (compared to $8.50 today).

Old Town Records Collection* NYC Municipal Archives.

Old Town Records Collection* NYC Municipal Archives.

One can see that popular dog breeds were spaniels, poodles, and pugs, among others. Owners seemed to favor royalty-inspired names such as Prince and Duke.

New York City today is a dog-loving city, and it is clear from these records that this has been the case for a very long time. Look for future blogs that describe the rich and fascinating content of the Old Town collection.

*All photos are from: Old Town Records Collection, MS 0004, Subgroup 4, Series 6, Subseries 3, Vol. 28: License Book, Dogs, 301-601, 1896 July 1-1897 July 8

We’ll assume Mr. and Mrs. Clinton B. Nichols, of Queens County, obtained a license for their dog, ca. 1890. Borough President Queens photograph collection. NYC Municipal Archives.

Archival processing and digitization of the Colonial Old Town Records is made possible by the National Historical Publications and Records Commission.