The Municipal Archives holds numerous of collections relating to the city’s role in the American Civil War. Many relate to the fraught topic of service in the military, an issue that simmered at the intersection of immigration and racism, finally boiling over in New York in July 1863. Archives collections document military recruiting efforts, aid for families of volunteer soldiers, and the explosive issue of paying substitutes to be soldiers. The Draft Riot Claims collection has garnered particular interest from scholars. To explain the importance of this collection, some background is in order.

New York and the Civil War

When it comes to the Civil War, New York City presents a Jekyll and Hyde personality to the historian. On one hand, New York (Manhattan, to be precise, because the boroughs weren’t amalgamated until 1898 and Brooklyn’s attitude towards the war differed from Manhattan’s) was the site of Abraham Lincoln’s legendary February 1860 Cooper Union speech, which propelled him to national prominence as a potential presidential candidate. Moreover, Manhattan rapidly assembled an army regiment composed of firefighters in response to President Lincoln’s call for troops to protect Washington DC immediately after the fall of Fort Sumter in April 1861. But New York City was also the “City of Sedition,” in the phrase of historian John Strausbaugh. It voted decisively—twice—in favor of Lincoln’s opponent, and on the day of Lincoln’s inauguration Mayor Fernando Wood declined to allow the American flag to be flown over City Hall. Much worse was to come. In July 1863 Manhattan was the site of what is still the worst spasm of urban domestic violence in American history—the New York City Draft Riots.

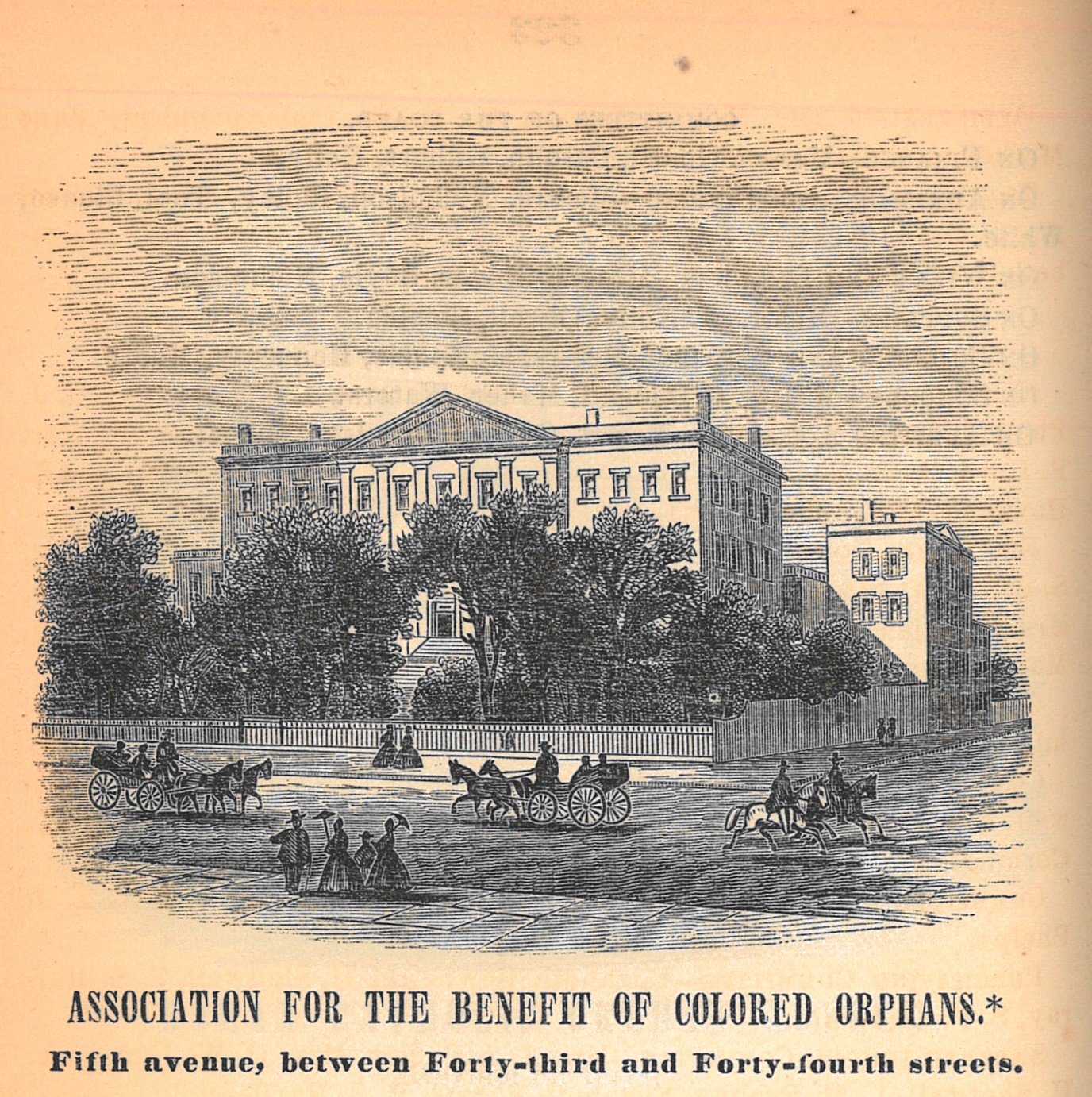

The Colored Orphan Asylum, Fifth Avenue between 43rd and 44th Streets, Valentine’s Manual, 1864. NYC Municipal Library.

1863: the Critical Year

The Union Army was in trouble in mid-1863. After two years of battlefield failure, the two-year tour of duty for large numbers of volunteers was coming to an end. Confederate commander Robert E. Lee, knowing the industrial superiority of the Union was something his generals and their troops could not overcome in the long term, made the decision to invade the North. Lee hoped to win a decisive military victory and convince the Union to enter peace negotiations. The Confederate army entered Pennsylvania in June and drew not just Federal troops but the militias from several nearby states, including nearly 16,000 from New York (1).

In March 1863, Congress passed the first national conscription law in American history to replenish the army. Mandatory military service was not popular anywhere, but in New York City there was an especially powerful reaction to the prospect of a draft. When Lincoln made his momentous decision to release the Emancipation Proclamation in early 1863, it confirmed that the goal of the conflict was eliminating the institution of slavery, not merely preserving the Union as Lincoln had previously insisted. Irish immigrants in New York City feared that emancipation would result in Black workers migrating to the North and competing with them for jobs. Their concern was not unfounded. In the months immediately prior to the implementation of the new draft law, Black workers had been hired to replace Irish longshoremen who had struck for higher wages (2).

In the early 1860s, Irish New Yorkers, who represented around a quarter of the city’s population (3), were overwhelmingly working class. The Tammany Hall political machine courted the Irish vote, and the city elected a Democrat mayor despite New York State overall voting Republican in the 1860 presidential election. This created a highly combustible mix, with many local politicians openly hostile to the war, which had become a dreadful source of carnage. The new draft law had an enormous loophole allowing those with $300 to buy their way out of service—an amount out of reach for the working class—and when posters went up in July announcing the conscription process, the city exploded.

Claim made by Ann Garvey for the death of her husband during the riots. Draft Riot Collection. NYC Municipal Archives.

The Draft Riots and Draft Riot Claims

The first week of July 1863 was a turning point for the military prospects of the Union. The titanic battle at Gettysburg resulted in a decisive victory for the North, driven more by battlefield heroics than inspired generalship. After Gettysburg, Lee never again threatened the North. Immediately after Gettysburg’s conclusion, Grant’s siege of Vicksburg succeeded on July 4, ensuring Union control of the Mississippi and launching Grant’s rise to eventual command of all Union armies. Although the victories at Gettysburg and Vicksburg were front-page stories in New York newspapers, they neither portended a near-term end to the war nor eliminated plans for the draft. Although an initial drawing of names took place without incident on July 11, the resumption of the draft on July 13 was disrupted by an outburst of violence. The ensuing three days saw arson, looting, and widespread violence. Thousands of rioters roved through the streets from Lower Manhattan to Harlem, concentrating their fury on Blacks, on police who attempted to quell the violence, and on anyone they associated with abolition or pro-Union sentiments. Armories, factories, shops, newspaper offices, churches, and police stations were attacked, as were private dwellings.

In one of the riot’s most notorious acts the Colored Orphan Asylum on Fifth Avenue was destroyed by arsonists, although more than 200 children escaped. With the police outnumbered and the majority of the city’s militia sent to Gettysburg, the city was, in the words of one historian, in a state of “utter anarchy.” (4) Toward the end of the third day of riots, army and militia units arrived in Manhattan. When 4,000 troops marched through the city on July 16, the riots quickly ended. The death toll from the riots has been debated for 160 years—119 has often been cited, but numbers ten times larger have been proposed. The violence against Black New Yorkers was especially horrific, although studies have concluded that most riot deaths were rioters, killed by police or the army.

Claim of Frederick Johnson. Draft Riot Collection, 1863. NYC Municipal Archives

Inventory list in claim of Frederick Johnson, 1863. Draft Riot Collection. NYC Municipal Archives.

The City’s Response and the Draft Riot Claims Collection

In the aftermath of the violence, city officials and some merchants and wealthy citizens responded to the riots in unexpectedly impressive ways. Rioters were identified, arrested, tried, and sentenced to prison--although many additional Grand Jury indictments were never pursued. A few police officers were brought before the Board of Police Commissioners on charges of dereliction of duty during the riots. These included one Sergeant Jones, whose trial—and newspaper coverage of it—produced an early use of the concept and phrase “equal protection under the law,” to be codified in 1868 in the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution. (5) A committee of merchants raised $40,000 and distributed it to Black families, an effort in private philanthropy that was independent of official efforts. The City Council and Board of Supervisors authorized up to $2 million to cover the $300 commutation fee for “firemen, policemen, member of the militia, or indigent New Yorker who could prove that his induction into the army would cause hardship to his family,” a remarkable provision that historian Adrian Cook noted could have prevented the draft riots in the first place. (6) Finally, the city and state authorized $2 million in bonds to reimburse claimants for losses incurred during the riots. Claims began to flood into City Comptroller Matthew T. Brennan’s office just ten days after the riots. They were reviewed by insurance examiners, then scrutinized painstakingly by a Special Committee on Draft Riot Claims appointed by the Board of Supervisors.

The Special Committee performed its work by meeting claimants in person, questioning them directly about their experiences. The documentation of the Special Committee’s work constitutes the Draft Riot files held at the Municipal Archives. Most of the Draft Riot Claim files were thought to be lost before hundreds were discovered in 2019 in a Brooklyn warehouse. The recommendations of the Special Committee—subject to a vote of the Board of Supervisors—resulted in payments of more than $970,000, (7) equivalent to $24 million today. (8)

Although the great bulk of claim reimbursement dollars were distributed to White property owners and businesses, the Special Committee publicly committed itself to prioritizing the review of Black claimants given the degree of suffering and need that resulted from their losses in the riots. This was in fact done, assisted by support from the Police Department-actions that legal scholar Andrew Lanham characterized as “a remarkable degree of race-conscious remedies for the time.” (9) Still, because Black New Yorkers were overwhelmingly poor, the sum of their claims amounted to less than $20,000, barely 1% of the claims by Whites. (10) Overall, Black riot claim compensation was “negligible,” in the opinion of historian Barnet Schechter.(11)

Claim made by Maria Barnes, teacher at the Colored Orphan Asylum. Draft Riot Collection. NYC Municipal Archives.

The Municipal Archives collection of Draft Riot Claims offers historians a variety of insights into this important historical event and into the lives of mid-19th century New Yorkers. Ann Garvey requested compensation for the death of her husband Patrick, “caused by a gun-shot wound inflicted upon his body…while the said Patrick was peacably [sic] attending to his usual business avocations” (the claim was denied). At one end of the economic spectrum, attorney Abram Wakeman, New York’s postmaster and a friend of Abraham Lincoln, listed hundreds of books from a lost library that he estimated at more than 2,000 volumes. His claim’s list of possessions ran to more than 700 lines on 32 pages. In contrast, Black claimants such as Frederick Johnson listed their lost possessions on just a couple of dozen lines. Despite their modest size, the requests made by Black claimants were treated with casual contempt by examiner Frederick R. Lee, who wrote of Anna Addison’s claim, “the jewellery [sic] of Negroes is invariably nothing but gilt.”

Such insights may emerge when an archival collection is examined closely: what may have been created for one purpose will reward the historian for other reasons. In the case of the Draft Riot Claims collection, the documents provide not only the poignant descriptions of lives and possessions lost through violence but also evidence of social and political themes: how “ordinary black women were profoundly committed to respectability during and following the Civil War;” (12) an insistence by claimants on assertions of the emotional as well as financial value of lost objects that “drew on the material history of their possessions;” (13) and “a remarkable degree of race-conscious remedies [that] offers an intriguing prehistory on the strategic use of administrative agencies to advance civil rights claims in the twentieth century.” (14)

The Draft Riot Claims Collection has been recently inventoried. Visit CollectionGuides

for further information.

Mr. Robert Garber is an intern in the Municipal Archives.

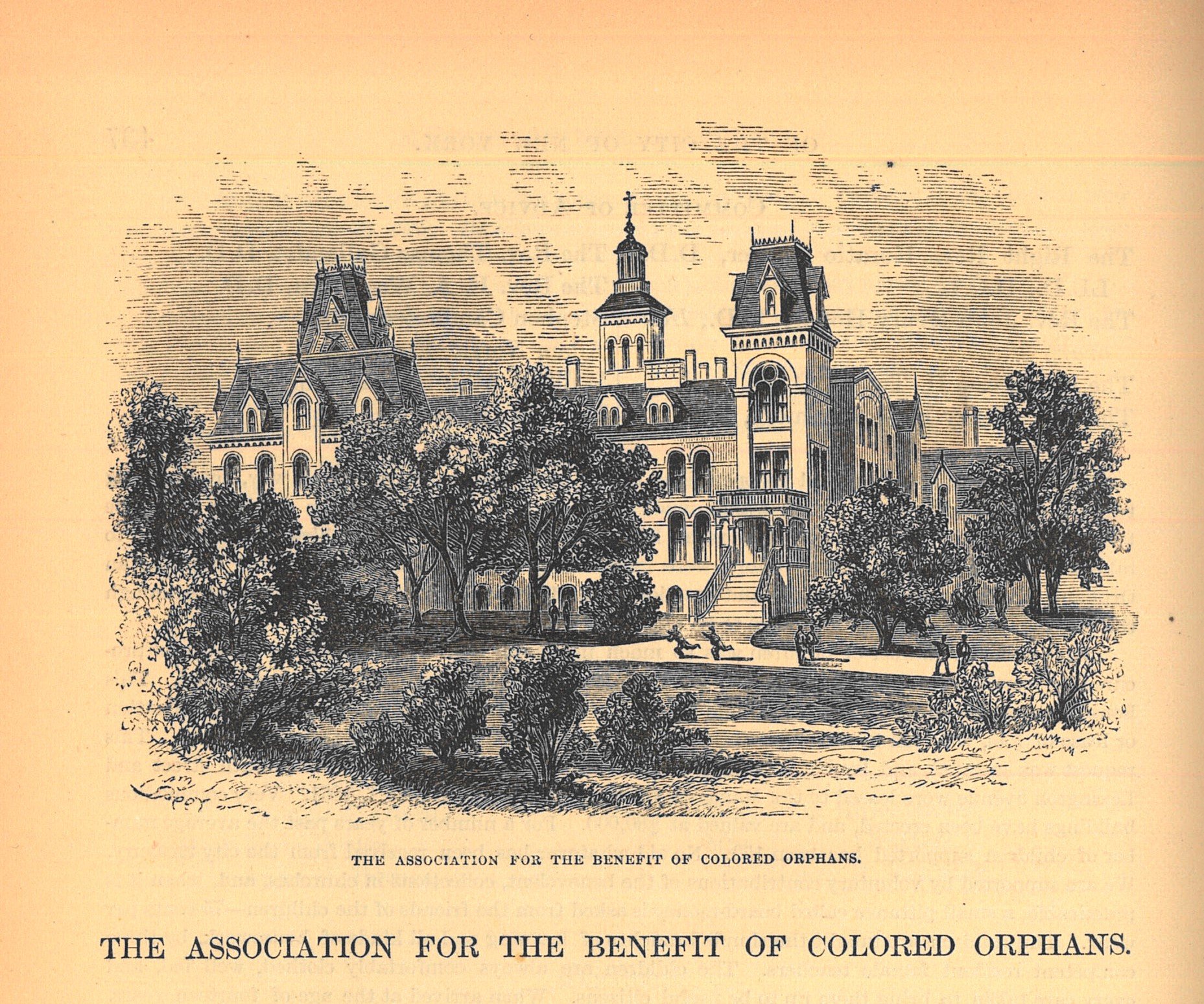

The New Colored Orphan Asylum, Tenth Avenue and 143rd Street, Manhattan. Valentine’s Manual, 1870. NYC Municipal Library.

Sources

1. Strausbaugh, John. 2016. City of Sedition: The History of New York City During the Civil War. Hachette, page 267.

2. Albon P. Man Jr. 1950. The Irish in New York in the Early Eighteen-Sixties. Irish Historical Studies 7(26): 88-89; “The Right to Work”, Daily News 14 April 1863 page 4.

3. nyirishhistory.us/wp-content/uploads/NYIHR_V19_01-The-New-York-Irish-In-The-1850sLocked-In-By-Poverty.pdf

4. Strausbaugh, page 272.

5. Lanham, Andrew J. 2023. “Protection for Every Class of Citizens”: The New York City Draft Riots of 1863, the Equal Protection Clause, and the Government’s Duty to Protect Civil Rights. UC Irvine Law Review 13(4): 1067-1118

6. Cook, Adrian. 1974. The Armies of the Streets: The New York City Draft Riots of 1863. The University Press of Kentucky, page 174.

7. [Brennan, Matthew T.] Communication from the Comptroller, Relative to Expenditures and Receipts of the County of New York, on Account of the Damage by Riots of 1863. Document No. 13, Board of Supervisors. Volumes I-IV. [Note: all four volumes are in the library of the NewYork Historical Society; volume II is also online at https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/45fd8ea0-cb9c-0130-ab53-58d385a7bbd0/book]. $970,000 represents totals from vol I page 66 and vol II page 61.

8. https://www.in2013dollars.com/us/inflation/1863?amount=970000

9. Lanham, page 1103.

10. Schechter, Barnet. 2005. The Devil’s Own Work: The Civil War Draft Riots and the Fight to Reconstruct America. Walker & Co, page 250.

11. Schechter, op. cit.

12. Dabel, Jane E. and Marissa Jenrich. 2017. Co-Opting Respectability: African American Women and Economic Redress in New York City, 1860-1910. J. Urban History 43(2): 312-331.

13. Cohen, Joanna. 2022. Reckoning with the Riots: Property, Belongings, and the Challenge to Value in Civil War America. J. American History 109(1): 68-89.

14. Lanham, page 1103.