PRETTY GIRL CHARGED WITH CLEVER SWINDLE:

WOMEN AND CRIME IN EARLY 20TH-CENTURY NEW YORK CITY

Badgers and sneak thieves, dishonest servants and disorderly houses, Fagins, shoplifters, con artists and grifters. Who were these pretty girls and hard women?

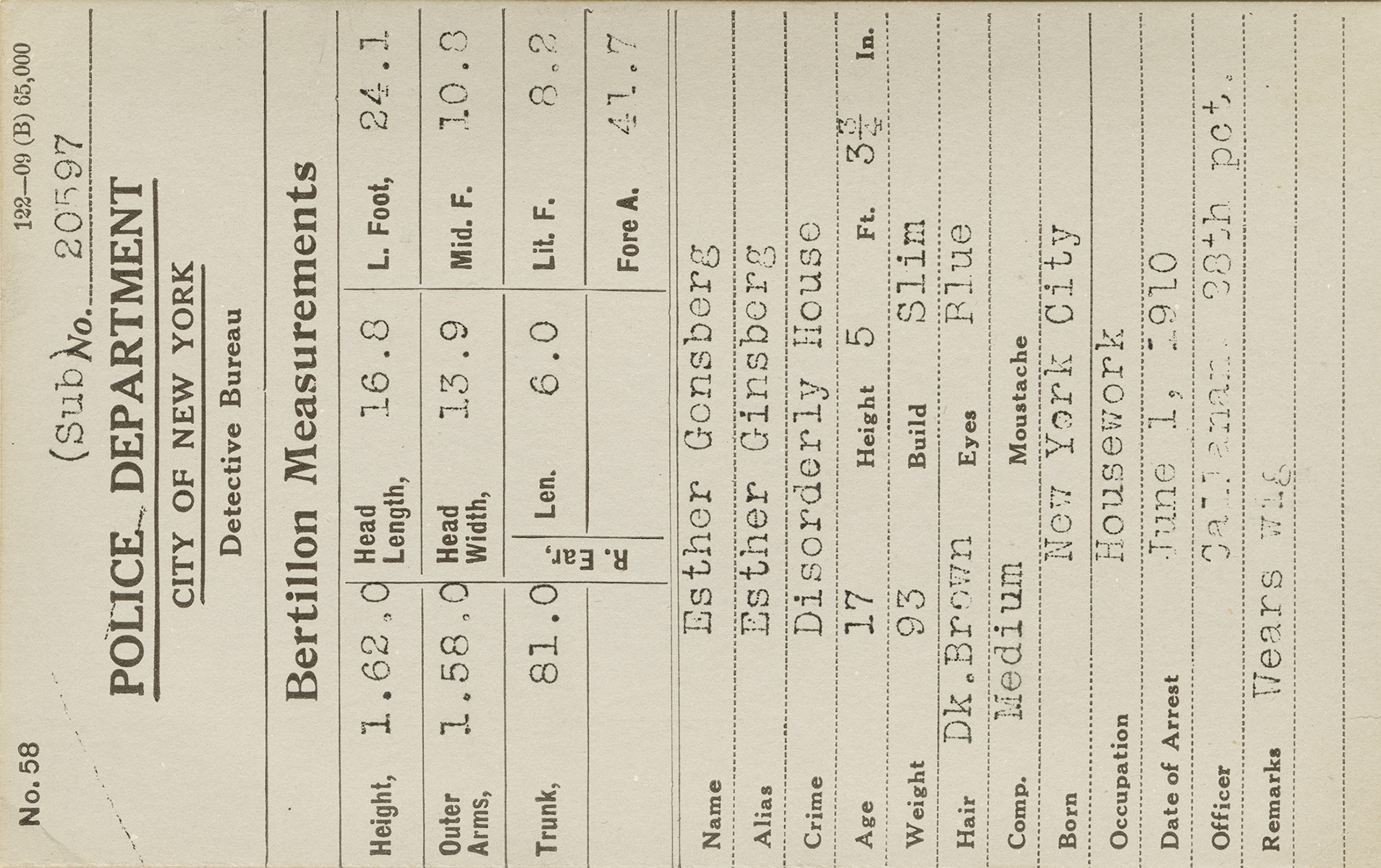

Sadie Schoen, the “Pretty Girl” from Austria caught conning a shopkeeper, made headlines with her “clever swindle.” Maggie Moore, with her sad, weathered face, standing only 5 feet, and weighing 107 pounds, was a 35 year-old Irish woman arrested for malicious mischief in 1910. Lena Keller, a tough, plain-looking woman from Germany, faced a homicide charge. But look at her occupation—midwife—did she provide an illegal abortion as many midwives did? Slim, blue-eyed, wig-wearing Esther Gensberg, 17, was arrested for keeping a disorderly house. This was not a violation of cleanliness, but the formal name of the offense for running a brothel. Tattooed Lillie Bates, 23, was arrested in 1909 as a badger, part of an old con to lure men into a compromising position and then blackmail them.

Life was never easy for women in New York and the way they were treated by the law and the press varied according to their social class. Was it poverty or hysteria? Was she an “idle housewife” or a “hard-working stenographer”? Was it “kleptomania” or “grand larceny”?

BERTILLON CARDs

The New York City Police Department opened their first “Rogues Gallery” in 1858, with photographs of recidivist criminals taken by a portrait studio. However, the story of police photography really begins with Alphonse Bertillon in Paris, France around 1880. Bertillon did not invent police photography, but he gave it rules and scientific methodology. From a family of scientists (his father was a famous statistician), Bertillon had a job as a police clerk that required him to describe prisoners and file photographs. He quickly realized the assignment was pointless as there was no consistency to the descriptions or how the photographs were produced. His invention was to use scientific calipers to take 10 precise measurements of various bones in the human body (and record other features such as eye color, scars, etc.) reasoning that no two people would have the same set of dimensions.

For the photographs Bertillon specified the front portrait and profile pictures that became the standard “mug shot.” He wrote specific instructions on how these photographs should be made, including poses, lighting, and distance from the prisoner. In 1897, the NYPD built a studio, trained police officers as photographers, and adopted the Bertillon method. With development of fingerprinting for criminal identification in 1920, the “Bertillon” measurements were phased out. But the dual photographs and descriptive information remained.

Brooklyn Stand-Ups

The 3,000 Bertillon cards in the NYC Municipal Archives were once part of a vast Rogues Gallery, which by 1920 contained over 50,000 criminals. In 2011, the Archives accessioned the NYPD Photo Unit’s records dating from 1897 to 1975. The collection contained some of the original Bertillon glass-plate negatives from 1897, crime-scene photographs from 1915 to 1975, and the Brooklyn Stand-Up series.

The stand-up mug shot was implemented by the NYPD in 1918. The stand-up was directed for recidivist criminals or those accused of a major crime. When known collaborators were arrested they were photographed in a group stand-up.

This exhibit was curated by Quinn Berkman and Michael Lorenzini of the NYC Municipal Archives for Photoville 2016 in Brooklyn Bridge Park.