Since 2015, the Municipal Archives has participated in the annual New York City Photoville festival. Photoville is a citywide two-week pop-up exhibit. The main venue is directly under the Brooklyn Bridge at the corner of Water and New Dock Street in DUMBO, Brooklyn. This year, it runs from June 1-16, 2024. For the core exhibits, each Photoville participant transforms a shipping container into a temporary gallery. Our exhibit this year celebrates 100 years of WNYC.

Municipal Building with WNYC radio antennae, July 18, 1924. Photo by Eugene de Salignac. NYC Municipal Archives.

From 1924 until 1997, WNYC radio was owned and operated by the City of New York for “Instruction, Enlightenment, and Entertainment.” WNYC turns 100 this year, and its history is intimately related to both City government and the NYC Municipal Archives. From the first broadcast on July 8, 1924, preserved in photographs by Eugene de Salignac, to historic broadcasts (both radio and television), the Municipal Archives is the repository of much of WNYC’s historical audio and video programs. The rest of its history has been preserved by the New York Public Radio Archives, founded in 2000. Its archivist, Andy Lanset, has spent more than two decades gathering ephemera, equipment, and lost recordings. He has been awarded several collaborative grants to digitize the recordings housed in the Municipal Archives and New York Public Radio.

WNYC’s first day on the air, July 8, 1924. (Earlier in the day - first broadcast at night) Grover A. Whalen, WNYC’s founder, (in tux) is joined by Public Address Operators Bert L. Davies and Frank Orth (seated) who is operating a wave meter. Photo by Eugene de Salignac. Department of Bridges/Plant and Structures collection. NYC Municipal Archives.

Grover Whalen, Commissioner of the Department of Plant & Structures launched WNYC Radio on July 8, 1924. Through their original programming and recordings made at City Hall events and press conferences, WNYC Radio reporters, engineers and producers captured a wide range of important cultural and political personalities. John Glenn and John F. Kennedy, Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X, Josephine Baker and Bob Dylan, astronauts and politicians, artists, musicians and poets all made appearances on WNYC. The founder of the Municipal Archives, librarian Rebecca Rankin, even had her own radio program on WNYC.

WNYC’s first issued program guide, The Masterwork Hour, December 1935. WNYC collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

Over time, WNYC Radio grew into both AM and FM stations, as well as a television station that enhanced the civic life of New Yorkers. In 1996, the City sold WNYC TV to a commercial entity. WNYC AM and FM continue today as the core of New York Public Radio, a non-profit organization that also includes WQXR, WQXW, New Jersey Public Radio, Gothamist and The Jerome L. Greene Performance Space.

Although the station was a very public presence in New York and often groundbreaking in programming and technology, it was not always beloved. Mayor John Francis Hylan used the station as a tool to attack his opponents, which led to a 1925 lawsuit and a judgement that WNYC could not be used for propaganda. His successor, Mayor James J. Walker, considered shutting it down, but it survived despite public calls for its elimination, including from mayoral candidate Fiorello H. La Guardia. Mayor La Guardia appointed Seymour N. Siegal as Assistant Program Director to “shut the joint down.” Instead, Siegel returned with a report on how the station could be improved. He saw value in the station as a means to make government more transparent and to educate the public on issues of health and safety. Siegel got a stay of execution from La Guardia as the station was put on probation and a broadcasting panel of experts from the networks studied the situation and eventually reported back to La Guardia with recommendations for what was needed to keep the station going.

WPA Federal Art Project poster by Frank Greco circa 1939 (colorized). NYC Municipal Archives.

WNYC Radio Map, ca. 1937. A.G. Lorimer artist. WNYC Archive Collections. https://www.wnyc.org/story/123806-artist-and-architect-a-g-lorimer

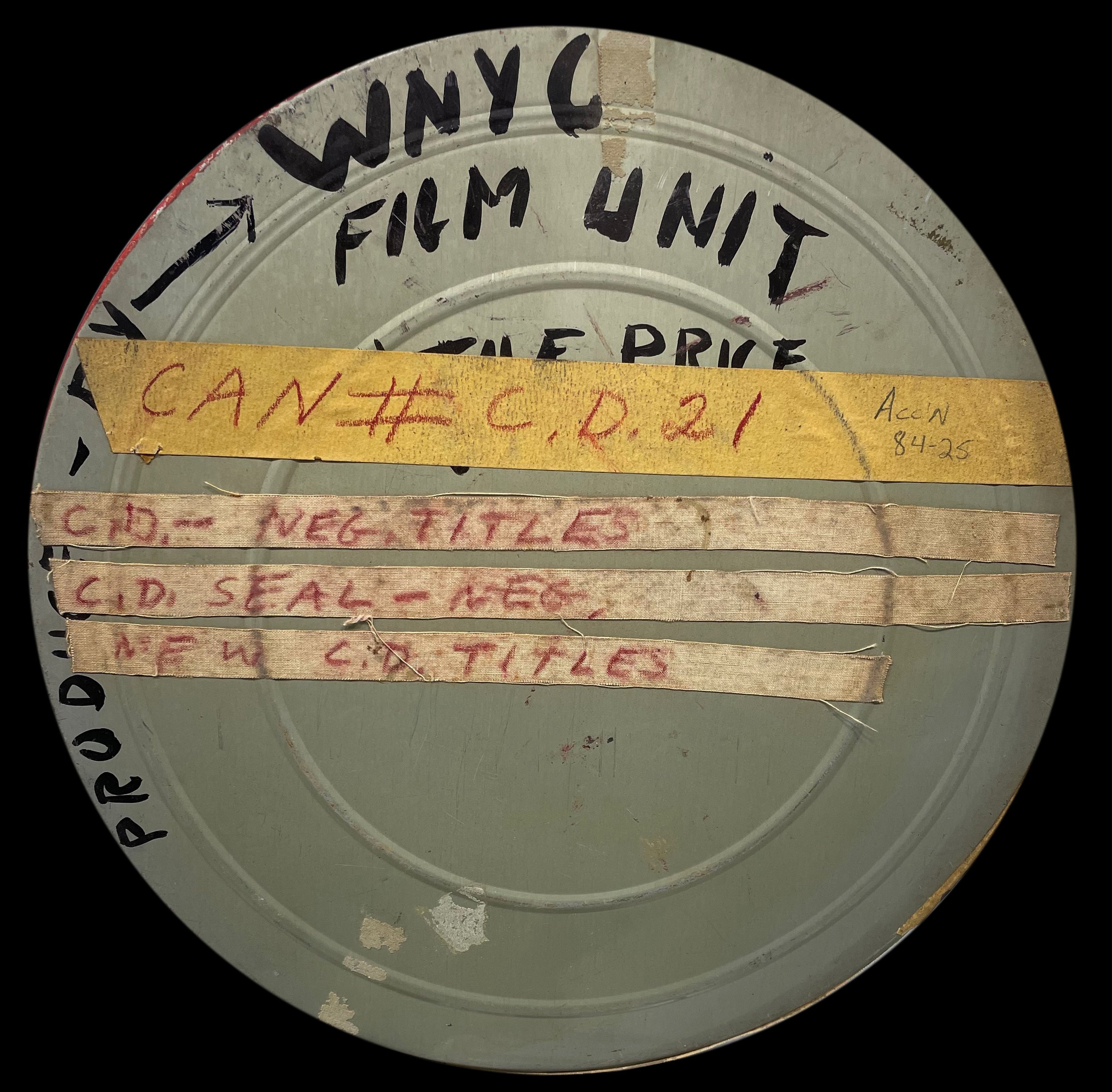

Original can from the WNYC Film Unit. WNYC collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

Meanwhile by the mid-to-late 1930s, the Federal Works Progress Administration (WPA) provided funding which underwrote half of the programming. It also supported construction of new studios for the station in the Municipal Building and a new transmitter in Greenpoint, Brooklyn. WPA artists even contributed murals and artwork for the studios. La Guardia changed his attitude and saw the station as an educational and cultural tool and began to use it as a way to talk directly to the people of the City. He also separated WNYC from the Department of Plant & Structures and created a new mayoral agency, the Municipal Broadcasting System, with Morris S. Novik as its director.

Title card from “Baby Knows Best,” a WNYC-TV production, ca. 1950s. WNYC collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

WNYC-TV cameraman in City Hall, ca. 1962. Photographer unknown. WNYC collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

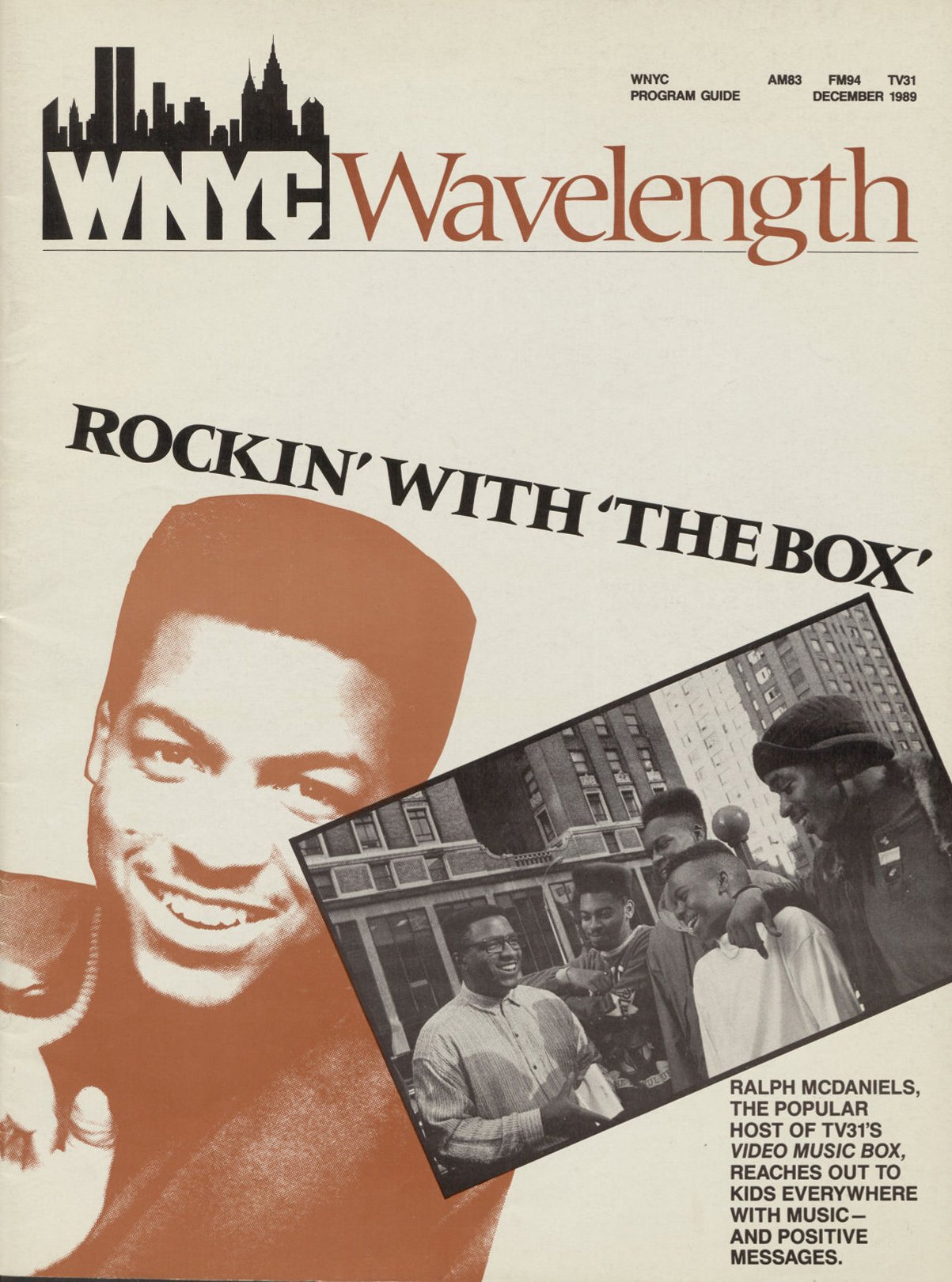

Ralph McDaniels, creator of Video Music Box, on the cover of Wavelength, 1989. WNYC Archive Collections.

After World War II, Siegel, fresh from five years in the Navy, became the second director. Siegel continued to develop new educational programming for the station, and in 1949 he created the WNYC film unit to develop short educational films for the new medium of television. By 1962, WNYC-TV had its own television channel, the first municipal TV station in the nation. Facing massive budget cuts, Siegel turned in his resignation in 1971. The 1970s were not kind to WNYC, and in 1975 it held its first on-air membership drive to raise money. In 1979 the WNYC Foundation was formed with the idea of eventual independence from the City. In the 1980s, WNYC-TV broke new ground, with the first LGBT TV news series, Our Time, which premiered in 1983, and Video Music Box, which was launched by a young employee, Ralph McDaniels, in 1984. It was the first TV program to regularly air rap videos.

Staff on the roof of the Municipal Building for the 53rd Anniversary of WNYC, July 1977. Photograph by Sal de Rosa. WNYC Archive Collections.

Nelson Mandela receiving the key to the city from Mayor Dinkins, June 20, 1990. NYC Municipal Archives. https://www.wnyc.org/story/mandela-in-new-york/

FM Transmitter on top of World Trade Center, 1986. Photograph by Lisa Clifford. NYC Municipal Archives.

After a tumultuous review, Mayor Guiliani announced the sale of WNYC AM & FM licenses to the WNYC Foundation in 1995. WNYC-TV was to be sold at auction to commercial bidders. June 30, 1996, was the last broadcast of WNYC-TV, and on January 27, 1997, WNYC AM & FM were officially on their own. Of course, it took a little while to move out of the ‘attic.’ It was not until June 2008 that WNYC transferred the studios from the tower of the Municipal Building to the current Varick Street location.

More challenges awaited WNYC. In September 2001, WNYC lost its FM transmitter in the collapse of the north tower of the World Trade Center. The AM station continued to broadcast using a telephone land-line patch. In August 2003, the northeast blackout plunged the city into darkness, but the station stayed on the air with candlelight and emergency generators. In 2012, the WNYC-AM transmitter site in the new Jersey Meadowlands was damaged by Hurricane Sandy, taking it off the air. And in March 2020, WNYC had to set up home studios for its hosts as the COVID-19 pandemic shut down offices. Independence for WNYC also meant the launching of new magazine programing, podcasting, and a bevy of Peabody and other awards for programming including work by the producers of Radiolab, Studio 360, On the Media, Soundcheck and others.

Recovery efforts at Ground Zero, September 2001. Photographer unknown, Mayor Rudolph Giuliani collection. NYC Municipal Archives.

The Masterwork Bulletin, May-June 1971. WNYC Archive Collections.

Fitting 100 years of this history into a 20-foot-long shipping container presented a challenge. An easy solution would have been to just illustrate some part of the station’s history, but that did not seem to be fitting for this momentous birthday. The early years of WNYC were well photographed by Eugene de Salignac, agency photographer, but the Municipal Archives had few photos from the 1970s and 1980s. Luckily WNYC engineer Alfred Tropea had taken some beautiful color slides of the Greenpoint transmitter site and WNYC operations. And the WNYC program guides started to include more colorful covers with photographs of some hosts. Although Photoville centers on photography, we knew to tell the story we would need to use archival photographs, ephemera, and audio clips to celebrate WNYC’s history and importance to the City of New York. Even then, the story is too broad to tell fully. The exhibit had to be an immersive experience, with audio and visual components, so we settled on using four panels, each with a collage of images. A timeline underneath each panel marks highlights in the station’s history. An audio montage accompanies the visual panels:

Brian Lehrer broadcasting from his home, March 2020. Wayne Schulmister/WNYC Engineering.

Not everything made the cut, and the reasons are rather random. The great blues musician Huddie ‘Leadbelly’ Ledbetter was a hugely important presence for WNYC in the 1940s, but the audio was hard to fit in. Pete Seeger and Woody Guthrie were also cut, but Bob Dylan’s first radio broadcast went in. Rebecca Rankin, despite her importance to the Municipal Archives, was cut from the exhibit, but stayed in the audio. For Photoville we wanted to include a panel discussion on modern photography with Edward Steichen, Margaret Bourke-White, Walker Evans, Irving Penn, and Ben Shahn from 1950 but it was hard to find a good short clip. Instead, we went with a rare interview with Diane Arbus, recorded shortly before her death in 1971. A 1961 Malcom X interview was left out and Martin Luther King, Jr. was included simply because the Malcolm X interview was not an official WNYC broadcast and the 1964 King event was an important City celebration. We had wanted to include something on gay rights in the wake of the 1969 Stonewall Riots, but we found a better clip of an ACT UP demonstration for more funding for the AIDS crisis, which happened to be recorded by a young reporter named Andy Lanset.

WNYC Transmitter building, Greenpoint, ca. 1980s. Photograph by Alfred Tropea, WNYC Archive Collections.

WNYC audio and WNYC-TV/Film collections are available from the NYC Municipal Archives and from the New York Public Radio Archive.

To learn more about WNYC’s history, follow Andy Lanset’s New York Public Radio History Notes Newsletter. Here are some highlights in addition to the links in this article.

The night WNYC became real: www.wnyc.org/story/wnycs-first-official-broadcast

WNYC and the Federal WPA: www.wnyc.org/story/wnycs-wpa-murals

The Plan and Promise of WNYC: www.wnyc.org/story/new-york-citys-silver-jubilee-plan-and-promise-wnyc

Morris Novik and a Model of Public Radio: www.wnyc.org/story/218821-morris-s-novik-public-radio-pioneer

WNYC’s ID – Hope for the World: www.wnyc.org/story/where-7-million-people-live-peace-and-enjoy-benefits-democracy

Lead Belly on WNYC Throughout the 1940s: www.wnyc.org/story/king-twelve-string-guitar-wnyc-regular-through-1940s

Christie Bonsack and Early WNYC: www.wnyc.org/story/christie-bohnsack-wnycs-first-director

WNYC – The Station that Dodged Bullets: www.wnyc.org/story/wnyc-station-dodged-bullets

WNYC’s Journey to Independence: www.wnyc.org/story/going-public-story-wnycs-journey-independence

WNYC – Visions of a Flagship Station for a Cultural Network: www.wnyc.org/story/1937-vision-wnyc-flagship-station-non-commercial-cultural-network

100 Years of WNYC, Audio montage, list of clips

Re-enactment of first 1924 WNYC broadcast, 1948

Sweet Georgia Brown, Ben Bernie and His Hotel Roosevelt Orchestra, 1925

Col. Lindbergh Tickertape Parade Reception, June 13, 1927

Emergency Relief Committee Orchestra, 1931

Station sign-off, December 1931

Rebecca Rankin, Municipal Librarian, 1938

News broadcast, 1938

World’s Fair station ID, 1939

Pearl Harbor attack broadcast, December 7, 1941

Mayor La Guardia war-time Talk to the People, January 2, 1944

Mayor LaGuardia reads the comics during newspaper strike, July 8, 1945

Audio from City of Magic, WNYC-TV/Film, 1949

AM and FM Station ID, January 11, 1950

Bert the Turtle, Duck and Cover, ca. 1952

Audio from This is the Municipal Broadcasting System, WNYC-TV/Film, 1953

Eleanor Roosevelt DJs Elvis Presley’s song Ready Teddy, February 6, 1957

Last run of the 3rd Avenue El, May 12, 1955

Footloose in Greenwich Village, May 6, 1960

Bob Dylan’s first radio appearance, October 29, 1961

John Glenn, first American to orbit the earth, February 20, 1962

President Lyndon B. Johnson, Gulf of Tonkin announcement, August 4, 1964

Martin Luther King, Jr. welcome at City Hall, December 17, 1964

Station ID, 1963

Diane Arbus, interviewed for Viewpoints of Women by Richard Pyatt, September 2, 1971

Shirley Chisholm announces run for presidency, January 25, 1972

WNYC Golden Anniversary, Mayor Abraham D. Beame reading proclamation, July 8, 1974

Mayor Ed Koch town hall in Jackson Heights, June 1, 1979

Transit Strike, April 3, 1980

“Voices of Disarmament” rally, June 14, 1982

Vito Russo’s Our Time: Episode 1 - Lesbian & Gay History, February 16, 1983

Philip Glass interviewed on New Sounds by John Schaefer, January 6, 1985

ACT UP demonstration at City Hall, Andy Lanset reporting, March 28, 1989

Ladysmith Black Mambazo, August 30, 1987

Mayor David N. Dinkins and Nelson Mandela in New York, June 20, 1990

Snap!, The Power, Video Music Box with Ralph McDaniels, WNYC-TV, September 14, 1990

Audio from Heart of the City with John F. Kennedy, Jr., March 2, 1994

WNYC Independence Celebration, January 27, 1997

Kurt Vonnegut, Reporter for the Afterlife, 1998

World Trade Center montage, September 11, 2001

Brooke Gladstone, On the Media, December 20, 2002

Blackout announcement, August 14, 2003

David Garland, NYPR takeover of WQXR, October 8, 2009

RadioLab intro, February 20, 2010

John Schaefer, Soundcheck live from The Greene Space, December 15, 2011

Hurricane Sandy aircheck, October 29, 2012

Brian Lehrer Show, first broadcast from his apartment due to COVID-19, March 16, 2020

Protests, September 4, 2020

All of It, Allison Stewart, October 21, 2021

New Yorker Radio Hour, May 11, 2024

Notes From America with Kai Wright, May 19, 2024

Morning Edition, Michael Hill with Andy Lanset on the Anniversary of WNYC, July 8, 2023