Walking around New York’s Chinatown today, you might not notice a lot of Chinese architectural characteristics. While Chinatowns like San Francisco and Los Angeles intentionally incorporated elaborate and colorful Chinese-roofed buildings and the signature Chinatown Gate as marketing tools, New York’s Chinatown lacks the same overt Orientalized character.

Though New York’s Chinatown doesn't fit the visual stereotype of a Chinatown, closer inspection reveals subtle architectural links to China. Through the resources of the Municipal Archives, it is possible to look back in time to the early decades of Chinatown to find even stronger architectural connections.

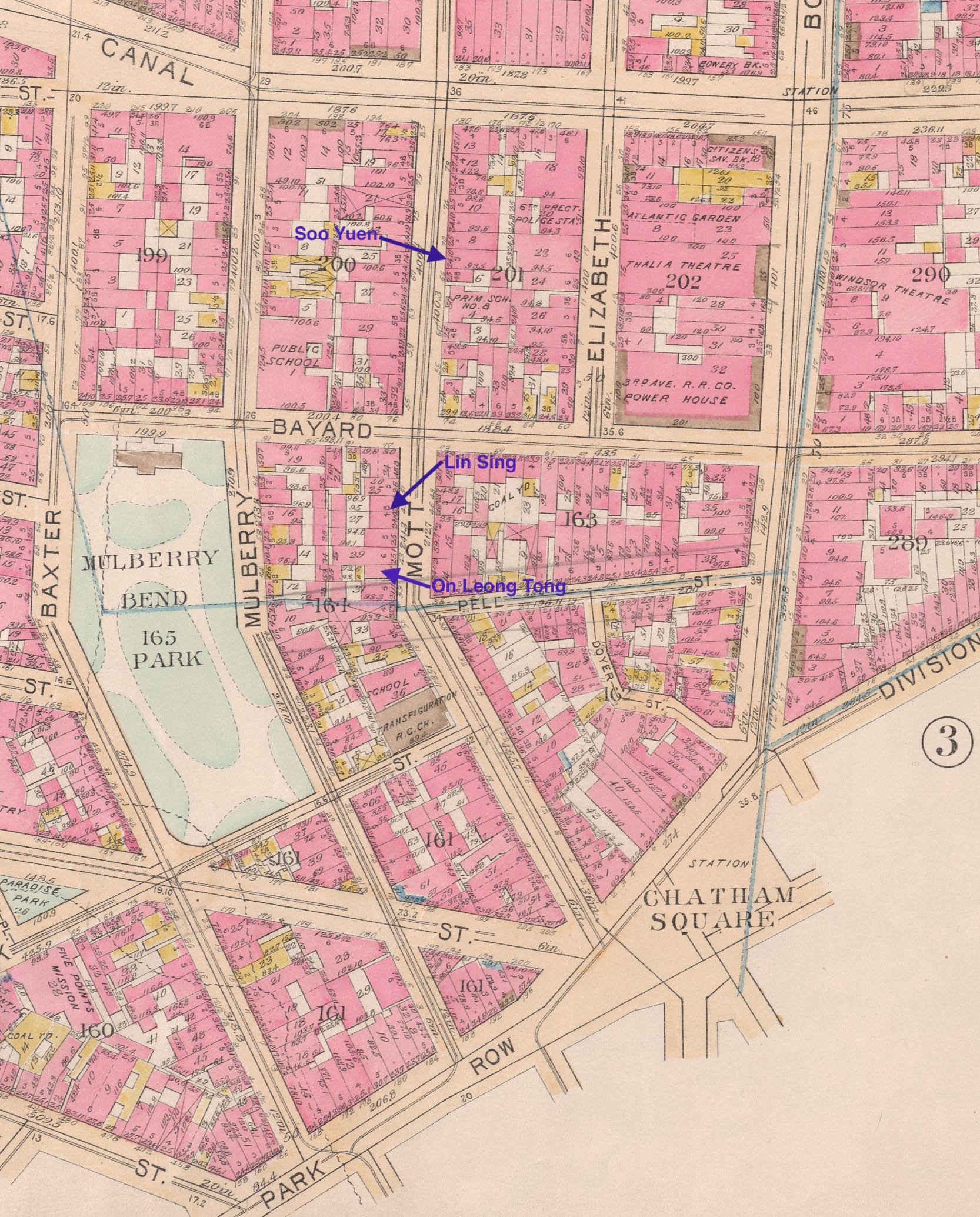

Image 1. Chinatown. Detail from the Bromley Atlas, Plate 5. 1897.

Located just a block from the notorious Five Points, lower Mott Street, Pell and Doyers Streets were home to successive waves of Irish, Jewish, and Italian immigrant residents. As a predominantly Chinese residential and business district began to coalesce into Chinatown in the late 1870s and 1880s, Chinese moved into the same old townhouses and tenements that had stood in the neighborhood for decades: Two to five-story buildings no different from the tenements found throughout the Lower East Side. With Chinatown’s population and economy expanding, the Chinese began to adapt these pre-existing buildings for their specific use and taste: Dry goods and grocery stores, import/export businesses, restaurants, boarding houses and family, merchant and district associations.

With no Chinese architects to turn to, Euro-American architects were hired to transform Chinese-owned or leased buildings along lower Mott, Pell and Doyers Street into versions of a building type more useful and familiar to the Chinese: The tong lau (唐樓). Though tong lau translates from Cantonese as “Chinese building”, the building type is a hybrid of many influences, among them Indian verandas brought by English colonizers to Hong Kong, and the southern Chinese shophouse, a mixed-use urban multifamily building. During the nineteenth century, the shophouse typology, of which the tong lau is an example, proliferated in areas of Chinese urban settlement the Pearl River Delta, its port city, Guangzhou, and colonial Hong Kong, the sources of most Chinese immigration to the United States in this period. Shophouse variants are found in Chinese settlements worldwide.

The character-defining features of the exterior of the tong lau are its deep, covered verandas or galleries — essentially covered porches extending across the facade that expanded usable living space in a hot, rainy climate and brought light and air into the often overpopulated building. Architect John A. Hamilton who completed a number of commissions for Chinese clients in New York Chinatown described the gallery as “essentially a chinese [sic] device and desired by them as being more like the stores in CHINA…” (Hamilton to Constable, BBL Folders Block 162, Lot 15). (Image 2.)

Image 2. Architect John A. Hamilton, who completed a number of commissions for Chinese clients, made a case for a gallery as a “chinese device” at 28 Mott Street. It was only approved once he redesigned it entirely of iron. Hamilton to Department of Building Superintendent Constable, August 3, 1895. Manhattan Department of Buildings Block & Lot Folder Collection, Block 162, Lot 15. NYC Municipal Archives.

The Chinese arrived in New York in the mid-nineteenth century, at a time when building codes were changing. After an untold number of deadly building fires, fire escapes for tenements only began to be required in 1860. The utilitarian nature of the fire escape was feared to mar the architectural character of buildings, opening up an opportunity for engineers, fabricators and others to design architecturally pleasing fire escapes. From the 1860s through the 1880s, patented designs often took the form of ornate wrought iron balconies spanning one or two windows connected by ladders or stairs to the street.[1] When designs for wooden galleries were deemed unlawful, Hamilton and his fellow Chinatown architects instead adapted the legally-required fire escape into galleries. (Image 3.)

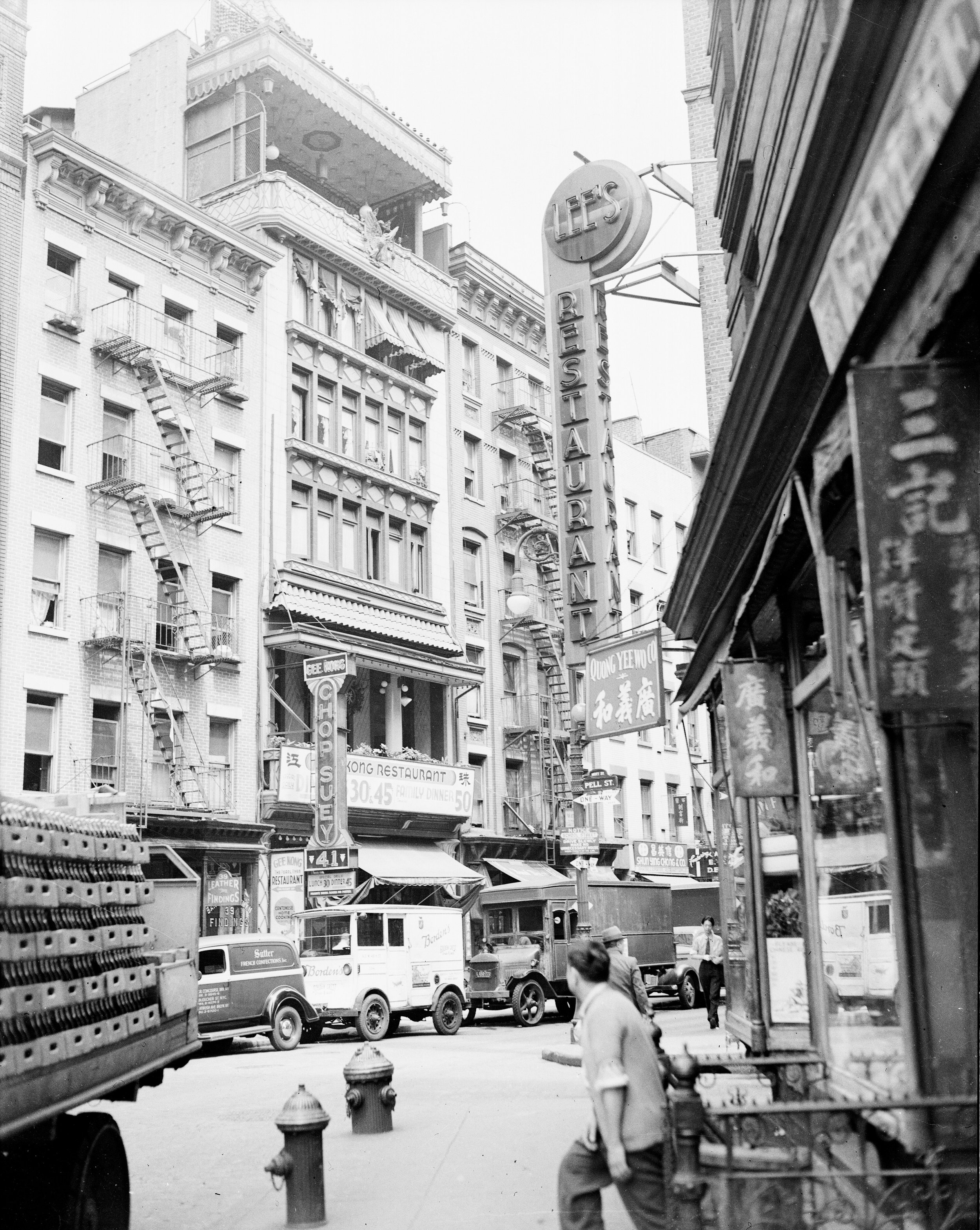

Image 3. Fire escapes adapted into tong lau-style galleries were once a common feature of Chinatown. Friends of China parade along lower Mott Street in 1937. No.s16-20 Mott Street were among the earliest buildings to be retrofitted with galleries. WPA Federal Writers’ Project Photograph Collection. NYC Municipal Archives.

The buildings most commonly transformed into the tong lau type were those occupied by family, regional, fraternal and merchant or business associations. These organizations emerged in the last quarter of the nineteenth century to provide mutual aid to Chinese in the US through economic, social and cultural support. Each association was organized according to affiliation, either surname (family); place of origin (district or regional), political or cultural (fraternal); or business ties (merchant). In the wake of the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, after which most Chinese, except for the merchant class, were categorically denied the right to immigrate or become naturalized American citizens, these associations played an important role in defending the rights and dignity of the Chinese in the United States.

The typical organization of a New York tenement included a store on the first floor with apartments above. Reflecting the economic and social organization of Chinatown, a tenement owned by an association might include a store on the first floor, restaurant or association meeting space on the second with a full-width, roofed gallery; housing on floors three and four; and an association meeting space on the fifth or top floor, also with gallery. A two or three-story building might have galleries on all upper floors (Image 3). The Municipal Archives collection of Department of Buildings architectural drawings and plans for Lower Manhattan, circa 1866-1978, contains drawings of merchant, district and family associations buildings that illustrate how elements of the tong lau manifested in both new construction and retrofitted buildings.

Since its founding in the 1890s, the On Leong Tong, later known as the Chinese Merchants Association, was one of the most powerful associations in Chinatown. By 1919, its members from chapters all across the United States had raised $70,000 to build their new clubhouse at 41 Mott Street. Architect Richard Rahmann of the firm William H. Rahmann & Sons designed a richly-detailed six-story building, with inset galleries at the second and sixth floor (Image 4). It included a restaurant for the public at the ground floor, dining facilities for club members at the second and third floor, sleeping accommodations for members on floors four and five, and a meeting room and library at the top floor. It was the first entirely new construction for a Chinatown association to incorporate both elements of the tong lau and a Chinese-inspired roof. Less than a decade later, architects Cohen & Siegel reworked the pagoda-like polygonal roof at the sixth floor into a highly-ornamented squared off “marquise” that would expand the usable space for the association’s top-floor meeting spaces (Images 5 and 6).

Now home to the Lee Family Association, 41 Mott Street was totally remodeled in the 1970s, and all exterior traces of Chinatown’s first “Chinese building” have been lost.

Image 4. Plans for the new On Leong Chinese Merchant’s Association, with galleries on the second and sixth floor, were filed by William H. Rahmann & Sons architects in 1919, but the building was not completed until October 1921. Manhattan Department of Buildings Plan Collection, Block 201, Lot 7. NYC Municipal Archives.

Image 5. Architects Cohen & Siegel reworked the Chinese Merchants Association’s sixth-floor gallery to create more space for association functions. The new design was richly detailed in copper. Manhattan Department of Buildings Plan Collection, Block 201, Lot 7. NYC Municipal Archives.

Image 6. When it opened in 1921, the Chinese Merchants Association was the most elaborate new building in Chinatown, with tong lau-style galleries at the second and sixth floor. The sixth floor was reworked in 1929, as shown in this WPA photo from the mid to late 1930s. WPA Federal Writers’ Project Photograph Collection. NYC Municipal Archives.

Founded in 1900, the Lin Sing is a district or regional association composed of 18 smaller organizations with a mission of advocating for the rights of its members. In 1926, the Lin Sing Association turned to architect Charles S. Clark to design their new six-story building at 47-49 Mott Street (New Building Application no. 400 of 1926; Image 7). This was the second brand new building in Chinatown based on the tong lau. Unlike the adapted tenements with their applied wrought iron fire escape galleries, this large new golden brick building, which occupies two lots, incorporated a recessed gallery spanning the second floor, where the association’s meeting space was (and still is) located. In an approximation of a Chinese roof, Clark designed a modestly curved green tiled rooflet over the gallery and another at the cornice (since removed). Prominent flagpoles featured on many Chinese-owned or leased buildings, and often flying the flags of the Republic of China (now Taiwan) and the United States. In Clark’s architectural drawing, the flagpole flies an American flag.

Image 7. The Lin Sing Associations’ new building golden brick building at 47-49 Mott (New Building application no. 400 of 1926) was the second purpose-built association in Chinatown to incorporate ta tong lau-style gallery into the second floor. Though specified in this drawing as copper, the modest Chinese-inspired roofs were clad in green tiles. Manhattan Department of Buildings Plan Collection, Block 201, Lot 7. NYC Municipal Archives.

The only drawing in the Department of Buildings collection that illustrates the adapted fire escape is surprisingly not from the turn of the twentieth century, but from 1946. (Image 8.) The Soo Yuen Association, representing families with the surname Lei, Fang and Kwang/Kuang, hired architect Irving Fiertag and his associate Foo F. Louis to create a metal-roofed gallery across at the top floor of their tenement building at 68 Mott. Still in place today, the metal brackets decoratively supporting the roof are based on traditional Chinese timber brackets called dougong.

Image 8. The Soo Yuen family association’s new fifth-floor gallery from 1946 took the form of the old-style fire escape adaptations popular at the turn of the century. Manhattan Department of Buildings Plan Collection, Block 201, Lot 3. NYC Municipal Archives.

Whether for observing Chinese New Year festivities, parades, or daily life in Chinatown, “chinese devices” like galleries offered both functional and familiar space in a cramped urban environment. Though most of Chinatown’s tong lau-style galleries are gone or altered, evidence from the Municipal Archives helps piece together a story of an immigrant community maintaining strong ties to China and among fellow Chinese.

Kerri Culhane is an architectural historian and planner. In 2019, she co-curated The Lung Block exhibition at the Municipal Archives. She is a PhD candidate in Architecture & Urban History at the Bartlett, University College London, where her research explores architectural change in New York's Chinatown from the 1870s to 1965.

[1] Originally under the purview of the Board of Health, and later the fire department, by 1892, all new fire escapes came under the review of the Superintendent of Buildings. Mary Elizabeth André, “Fire Escapes in Urban America: History and Preservation.” MA Thesis, University of Vermont, 2006, 27; 88-100.