WNYC Greenpoint Radio Transmitter, ca. 1937. A.G. Lorimer artist. WNYC Archive Collections.

July 8, 2024, marked the 100th anniversary of municipal broadcasting for the City of New York. On September 9th, from 7-9pm, WNYC will celebrate with a live radio broadcast from SummerStage in Central Park. Hosted by Brian Lehrer, the event will include beloved voices from WNYC and a lineup of live music, storytelling, comedy, trivia and more.

Scheduled to appear are WNYC’s All Things Considered host Sean Carlson, Brooke Gladstone and Micah Loewinger from On the Media, Alison Stewart from All of It, Ira Glass from This American Life, John Schaefer of New Sounds, and The Moth storyteller Gabrielle Shea. Plus, performances by Nada Surf, Freestyle Love Supreme, Laurie Anderson with Sexmob, and mxmtoon; and a DJ set by Donwill.

This event is free to attend, no RSVP required, and will be broadcast live on WNYC at 93.9 FM, AM 820, wnyc.org or on the WNYC app.

https://www.wnyc.org/events/wnyc-events/2024/sep/09/central-park-summerstage/

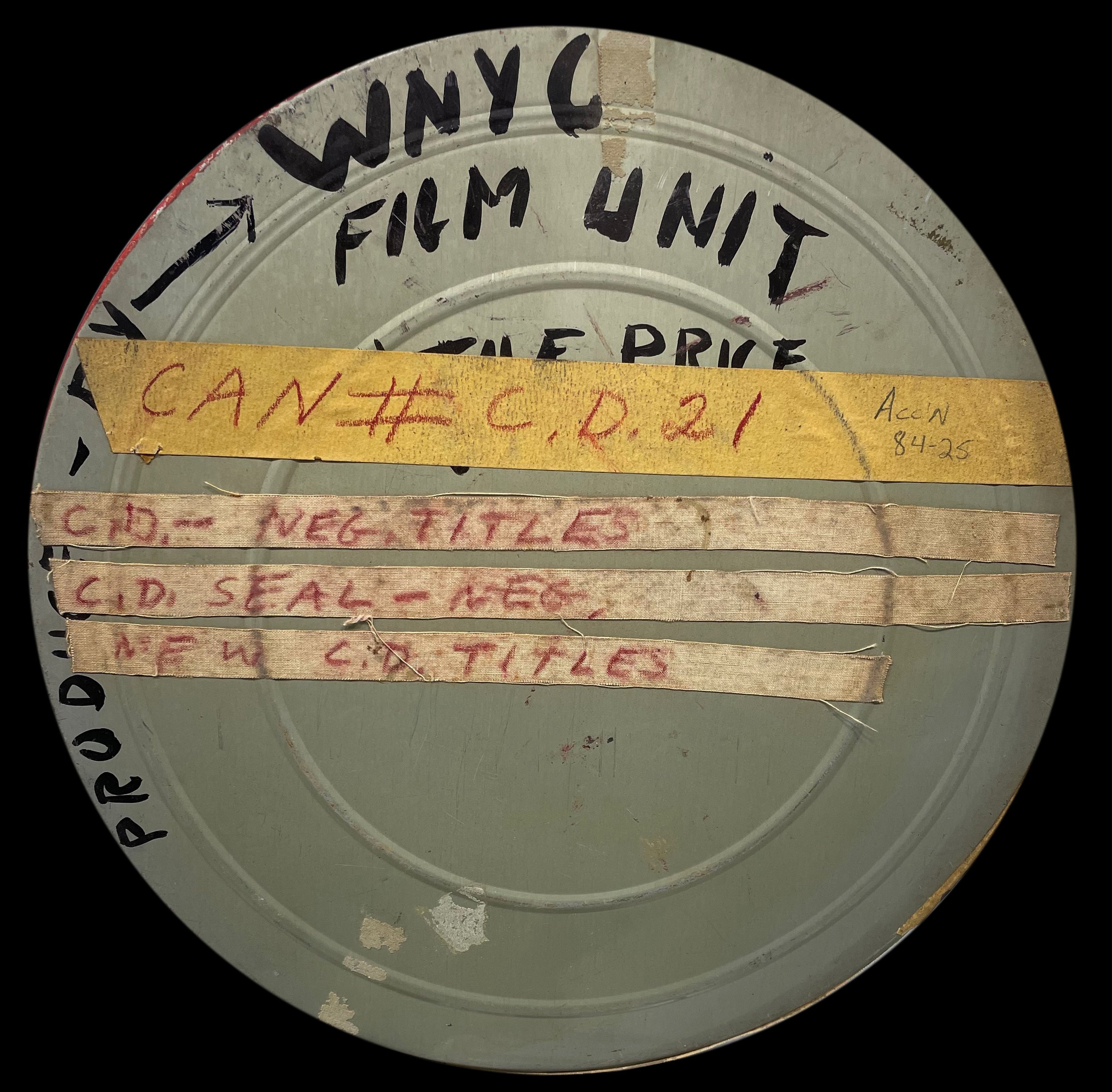

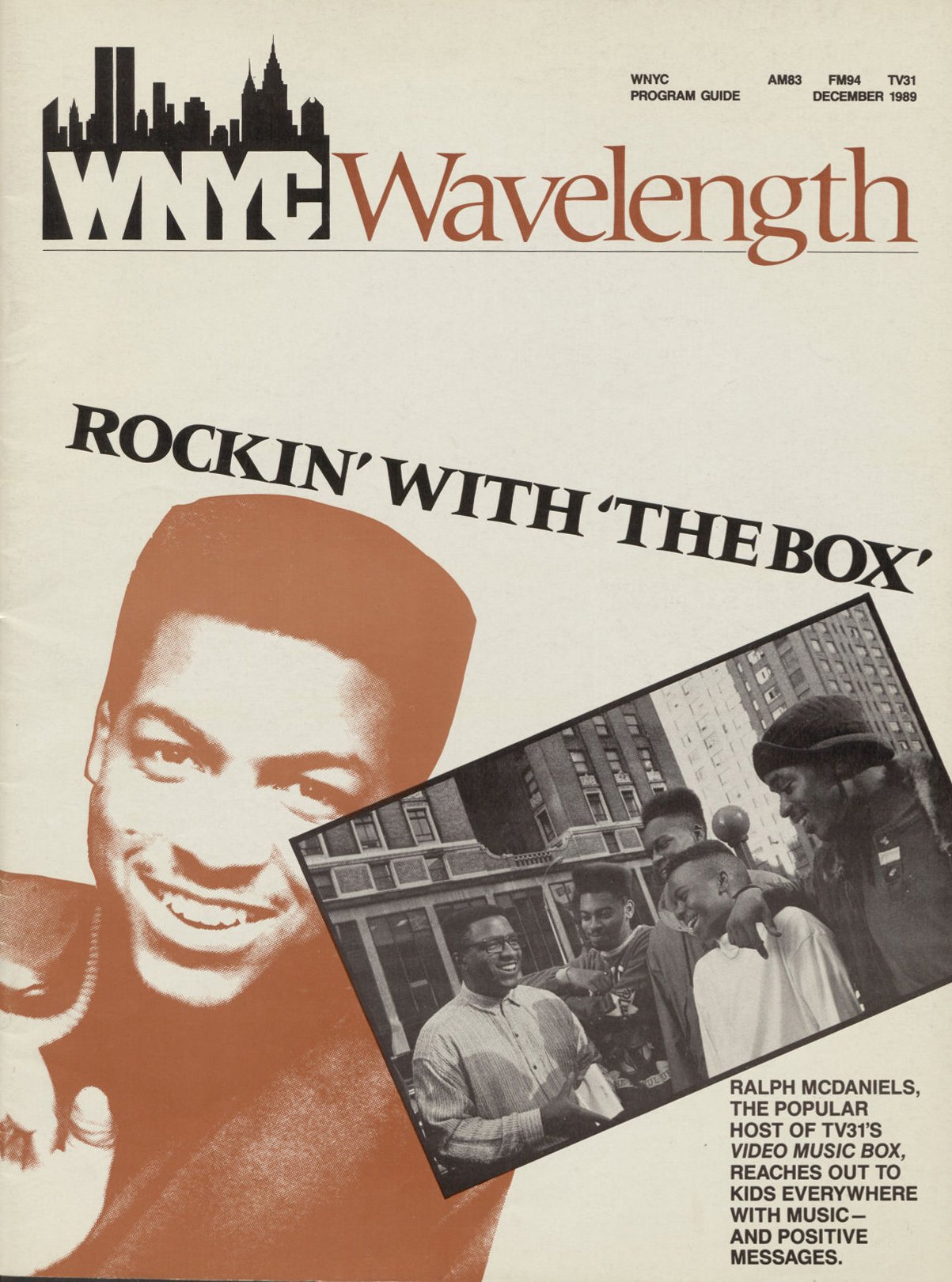

What began with WNYC, now the largest independent public radio station in the U.S., continues today with the city’s official broadcast network, NYC Media. They recently released a short documentary on the history of WNYC and NYC Media, which uses audio and video clips from collections now stored at the Municipal Archives.

The NYC Media documentary was inspired by the recent Municipal Archives exhibit 100 Years of WNYC, produced for Photoville 2024, which will soon be on display at the Municipal Archives headquarters at 31 Chambers Street.

Exhibit panel from 100 Years of WNYC.