Best wishes for a peaceful and joyous 2024.

For the Record will return in the new year.

Long Meadow, Prospect Park, January 2016.

For the Record will return in the new year.

Long Meadow, Prospect Park, January 2016.

As an intern at the Municipal Archives this fall, it has been my privilege to help process the NYPD Intelligence Records, aka the Handschu collection. Very large—more than 520 cubic feet—and in high demand, this collection is made up of records created by a unit of the New York Police Department Intelligence Division, the Bureau of Special Services, which had the goal of monitoring “subversives.”

Playboy Magazine, January 1967. NYPD Intelligence Records, NYC Municipal Archives.

The material now held by the Archives is the result of decades’ worth of NYPD surveillance and investigation of both groups and individuals. This material spans the 1930s–1990s but is concentrated in the 1950s–1970s, and is divided into several series: for instance, Series 1.1 is for photographic records, while Series 1.4 and 1.5 are dedicated to small and large organizations respectively. Most of my hands-on work involved Series 1.2: Numbered Communications Files, which are thousands of reports created between 1951 and 1972. The reports are eclectic in their subject matter but tend to coalesce around topics like demonstrations, labor disputes, and security for public figures. The amount of material in the folders ranges from a single sheet to multiple brochures and clippings.

While processing these files, I recently came across a manila envelope with the arresting inscription: “Alleged plot by Cuban Nationalist Assoc. to fire bazooka at N.Y. Playboy Club.”

NYPD Intelligence Records, NYC Municipal Archives.

Both pro- and anti-Castro activities are widely represented in the collection, but this particular case merited a closer look. Why the Playboy Club? And why a bazooka? Reading the enclosed Bureau of Special Services report, it became clear that despite their alleged target, the Cuban Nationalists Association’s grievance was actually with Playboy magazine. I also found that there had been previous terrorist incidents involving anti-Castro Cubans and bazookas.

The numbered BSS report is dated November 25, 1966, and has the subject line “Information that anti-Castro Cubans have discussed planting of a live bazooka shell at the Playboy Club, 5 East 59th Street, Manhattan.” Passing on information received by an FBI agent from an unknown source, it discloses: “The Cubans are allegedly angry with the Playboy management because of an article written in the October issue of Playboy magazine titled ‘Tropic of Cuba,’ by Pietro di Donato, in which the author described prostitution and homosexual circuses in Havana in 1939. They consider the article vicious and dirty and apparently are not satisfied with the apology tendered by the magazine.” Because the Cuban Nationalist Association had been tied to previous explosions between 1964 and 1966, the agent felt that this intelligence could not “be discounted.” This opinion may or may not be counterbalanced by the fact that interviews with group members led to statements like “the organization is currently disorganized and has no meeting place,” and also that a subsequent FBI report describes the information as coming from “a source, contact with whom has been insufficient to determine his reliability.”

NYPD Intelligence Records, NYC Municipal Archives.

NYPD Intelligence Records, NYC Municipal Archives.

NYPD Intelligence Records, NYC Municipal Archives.

Along with the bombing of a Cuban ship, the bombing of Karl Marx’s grave, and the detonation of a bazooka in a suitcase at the Cuban Embassy in Canada, the Cuban Nationalist Association had been connected with the firing of a bazooka at the United Nations during an address by Che Guevara on December 11, 1964. The event was covered in the New York Times in articles such as “Bazooka Fired at U.N. as Cuban Speaks; Launched in Queens, Missile Explodes in East River,” “Three Castro Foes Arrested in Firing Of Bazooka at U.N.” and “Bazooka hearing is set for Jan. 6; 3 Cuban Suspects Called ‘Cooperative’ in Court.”

The first article reports: “A single shell from the bazooka, a portable rocket launcher used by the Army, arced across the river from Queens and fell harmlessly about 200 yards from shore. The blast sent up a geyser of water and rattled windows in the headquarters just as Major Guevara, Havana’s Minister of Industry, was denouncing the United States. [...] Later, strolling through the delegates’ lounge in his green fatigue uniform and highly polished black boots, he said, with a languid wave of his cigar, that the explosion ‘has given the whole thing more flavor.’ But the police saw no humor in the incident. Had the rocket shell crashed against the glass-and‐concrete facade of the headquarters building, there would almost certainly have been casualties.” The weapon was identified as U.S. made. The “three Castro foes” of the second headline were members of the Cuban Nationalist Association, although the director of the group claimed to have no knowledge of the events. At their hearing, “Assistant District Attorney Edward N. Herman told the court, ‘Regardless of where one’s sympathies may lie…the United Nations is here in the City of New York, our guests if you will, and they have the right, I think, not to have bazookas fired at them.’”

FBI Report, December 5, 1966. NYPD Intelligence Records, NYC Municipal Archives.

FBI Report, NYPD Intelligence Records, NYC Municipal Archives.

FBI Report, NYPD Intelligence Records, NYC Municipal Archives.

Also included in the manila envelope were two pieces from the newspaper El Tiempo. The first was a Spanish-language article condemning Playboy, dated October 25, 1966 and entitled “Una Infamia de ‘Playboy’: ‘El Trópico de Cuba’” (English: “A Disgrace from ‘Playboy’: ‘Tropic of Cuba.’”

El Tiempo, October 25, 1966. NYPD Intelligence Records, NYC Municipal Archives.

El Tiempo, 1966. NYPD Intelligence Records, NYC Municipal Archives.

The second was a photocopy of an undated English-language article entitled “The Playboy Incident.” “No one sympathizes more with the anti-Castro Cubans than EL TIEMPO,” it begins. “In fact, many now in the picket lines against Castro, were in 1959 picketing the editor of EL TIEMPO at his home and his office, because he said Fidel Castro was a Communist and deserved no support from this country.” Having established the publication’s bona fides, it continues, “But we cannot understand the fanatics who get out of hand, who make use of an article in EL TIEMPO to commit crimes and wreak violence.” The article makes the points––not in this order––that the Playboy Club is a separate entity from the magazine, that the author of the offending article and the editor of Playboy had already both issued a public apology, and that “on careful reading, not one of the women with whom [the author] claims to have been intimate were Cuban. They were all foreigners living in Cuba.” Finally, the author exposes and repudiates the (alleged) plan to attack the club: “What the public did not know––and what we are revealing here for the first time is a result of the insidious rumours to the effect that EL TIEMPO, ‘sold out’ to the Playboy magazine: some hot-headed Cubans were planning to set off a bomb at the Playboy Club––which could have cost many innocent lives, including anti-Castro Cuban employees of the club itself.”

Playboy memo, December 6, 1966. NYPD Intelligence Records, NYC Municipal Archives.

NYPD Intelligence Records, NYC Municipal Archives.

Anticipating more controversy ahead of the publication of an interview with Fidel Castro in the January 1967 issue, Playboy Club co-owner Arnold Morton sent out a memo on December 6 in which he reminded his staff of the journalistic context behind this and other controversial interviews (“If you read Playboy regularly, I am sure you are aware of the wide range of personalities and subjects it deals with in each issue”) and rallies them to a defense of the brand’s core values (“This Castro interview may meet with strong reaction too, but Playboy Magazine has always believed in the right of groups or individuals to disagree. It is for this reason that the magazine often serves as a forum for persons and viewpoints that would otherwise never be published in a mass magazine”). With respect to the original “Tropic of Cuba” controversy, he quotes an apology from the article’s writer Pietro Di Donato: “At no point was it my intention to insult or defame the wonderful people of Cuba. As a man of 100% Latin origin, I have long been sympathetic with the plight of the Cuban people.” It should be noted however that this pan-Latin camaraderie was not shared by the author of the critical El Tiempo article, Miguel Angel Martin, who refers to Di Donato throughout as an “‘escritor’ ítalo-americano” (“Italian-American ‘writer’”).

In addition to the above typewritten reports and periodicals, the folder created by the Bureau of Special Services held a piece of paper covered in handwritten notes relating to the investigation. The sheet includes phrases like “Lee Lockwood, author of article, works with Cuban Mission,” the names of the Puerto Rican independence activist Juan Brás and El Tiempo editor Stanley Ross connected by arrows to the word “fight,” and my favorite, if I am reading it correctly: “4 plans to dynamite––none came off.”

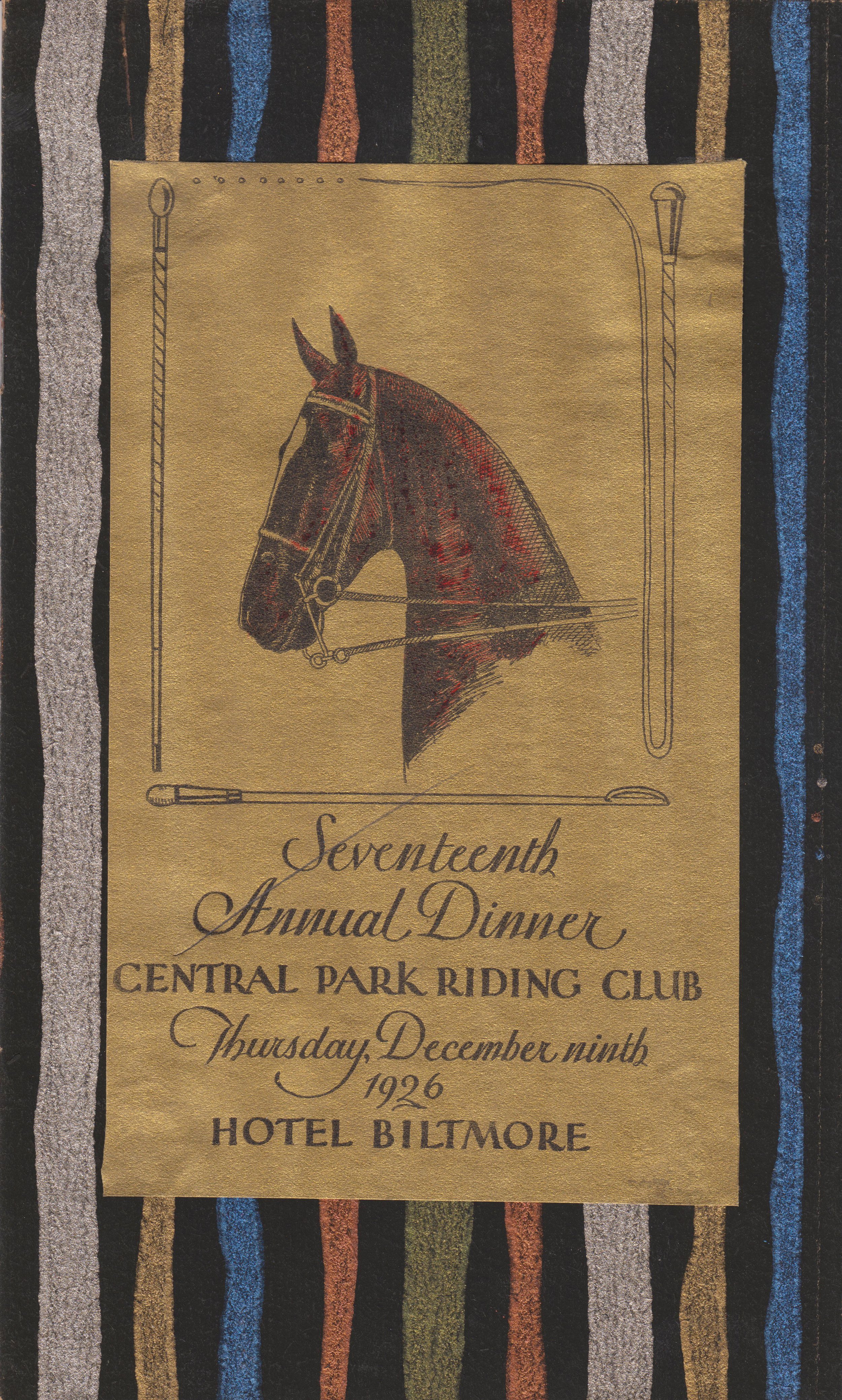

Central Park Riding Club dinner invitation, 1926. Office of the Mayor, Jimmy Walker, NYC Municipal Archives.

For more than one hundred fifty years visitors to New York’s Central Park have enjoyed picturesque vistas, rolling meadows, peaceful lakes, and a variety of charming architectural features.

Until recently, these pastoral scenes would have also included horseback riders cantering along the bridle paths. But after closure of the Claremont Riding Stables, located on Manhattan’s Upper West Side, in 2007, the horseback riders have largely vanished. Today—except for the southernmost area of the park where horse-drawn carriages still ply the roadway—horses are almost completely absent from the landscape.

A recent For the Record blog, Horsepower: The City and the Horse introduced the topic of the horse and its profound influence on virtually all aspects of city life. This week’s article looks at how the horse informed many of the design elements of Central Park.

Central Park, shelter for carriages and horses, preliminary study, front elevation, 1871. Jacob Wrey Mould, Architect. Department of Parks Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

Drives, Rides, and Walks

One of the most innovative features of Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux’ design for the park was their traffic circulation system that separated walkers, horseback riders, and horse-drawn carriages, creating intimate landscapes for each type of traveler.

The Drives were wide and sweeping, avoiding sharp turns to allow passengers in horse-drawn carriages to focus on the landscape. Park gardener Ignatz Pilat described the careful planning that went into their landscaping:

Central Park, Bridle Road Looking South, ca. 1913. Albert W. Schaad, photographer. NYC Municipal Archives collection. Schaad was a Central Park Zookeeper who created a scrapbook of his photos.

“The effect already produced and to be perfected in the course of time, throughout the length of the ‘Ride,’ is that of a pleasant country-road shaded by over-arching trees, mingled with shrubs and vines, spaces being left for more or less expanding views of open lawns, sheets of water, and other objects of interest which give the idea of extent and diversity; but wherever these open spaces would destroy the harmony of the landscape, a few scattered trees or low shrubs are so arranged as not to obstruct the view.”

The Rides, or bridle trails, generally hugged the perimeter of the park. For pedestrians, the Walks meandered through valleys, providing glimpses of the elegant carriage traffic nearby. All routes were surfaced and drained for safe passage in all types of weather. Where arteries met, the over- and underpasses of bridges were used as much as possible to separate carriage and horse traffic from pedestrians.

Central Park, Entrances and Gates, Entrance at 90th Street and Fifth Avenue, plan of entrance and section of adjoining wall, 1865. William H. Grant, engineer. Department of Parks Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

Another prescient feature of Olmsted and Vaux’ design for the park, also conceived to accommodate the horse, specifically horse-drawn vehicles, were the transverse roads. The original design competition specified that each submission must include at least “four or more crossing from east to west be made between Fifty-ninth and One Hundred and Sixth Street.” Olmsted and Vaux’ ingenious scheme was to sink the roads below grade. This made it possible to keep park visitors safely above the crosstown traffic, colorfully portrayed in their proposal as “coal carts and butchers’ carts, dust carts, dung carts” and “fire companies rushing their machines with fantastic zeal at every alarm.”

Winterdale Arch (Bridge No. 17)

Winterdale Arch, located along the West Drive near Eighty-Second Street, is named for its location on the Winter Drive, between Seventy-Second Street and 102nd Street. When planning the west side of the park, Olmsted and Vaux intended for this section to be planted with a variety of evergreens, to add color throughout the winter for carriage- and sleigh-riders.

Central Park, Bridge number 17 [Winterdale Arch], elevation of bridge and railing, 1861. Department of Parks Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

Stables and Workshops

After years of maintaining offices at Mount St. Vincent and the Arsenal, in 1869 the Central Park Board of Commissioners decided to construct “offices of Park administration” at a location that would be more easily accessible from all points in the park. The site proposed was at the northern edge of the old Yorkville Receiving Reservoir, on a sliver of land at a curve in Transverse Road No. 3, now called the Eighty-Sixth Street Transverse. The new offices would have included “engineering, architectural, and gardening apartments,” a stable with storage sheds for vehicles and machinery, and a separate building to house blacksmiths, carpenters, and other craftspeople.

Central Park, Offices of Administration, North Wing - East End, Details of Stable Building, Keeper’s Dwelling, etc. south front and west side elevations and longitudinal sections, 1869. Attributed to Jacob Wrey Mould, Architect. Department of Parks Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

Central Park, Offices of Administration, North Wing - East End, Details of Stable Building, Keeper’s Dwelling, etc. [detail], 1869. Jacob Wrey Mould, Architect. Department of Parks Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

Central Park, Offices of Administration, General Ground Plan of East End of North Wing, showing stable, sheds, yard and keeper's dwelling [detail], 1869. Attributed to Jacob Wrey Mould, Architect. Department of Parks Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

Mount St. Vincent/McGown’s Pass Tavern

In the latter part of the nineteenth century, a favorite stop for park visitors was the Mount St. Vincent Hotel. Built in 1881, it proved to be immediately popular with affluent New Yorkers, as the New York Times reported in 1886: “No matter how fast the team nor how elegant the equipage a turn ‘on the road’ is not done in proper shape unless it includes a bite or a sip in the Mount St. Vincent.

The Hotel was located in the quiet and rustic northeastern corner of the park, a landscape filled with steep bluffs and rough terrain. The old Boston Post Road—the original mail-delivery route from New York City to Boston—meandered between two rocky ridges in this area, and in the 1750s John Dyckman built a tavern to serve travelers in the vicinity of 105th Street and Fifth Avenue. Not long after, the McGown family purchased the land and tavern, running it successfully through the Revolutionary War. Hence the name of the small valley: McGown’s Pass.

Central Park, Mount Saint Vincent, design for a refreshment house, front elevation and side elevations, 1883. Julius F. Munckwitz, Architect. Department of Parks Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

The McGowns held the property until 1845, when they deeded the land and buildings to the Sisters of Charity of St. Vincent de Paul, who renamed the area Mount St. Vincent’s. Within a few years, the nuns had established a convent and school. To the existing structures, they added a two-story residence for the chaplain and a stately brick convent house that contained a beautiful chapel and large dining rooms. In 1856, before the nuns had consecrated their new chapel, they received word that the city would be taking their land for the creation of the new park.

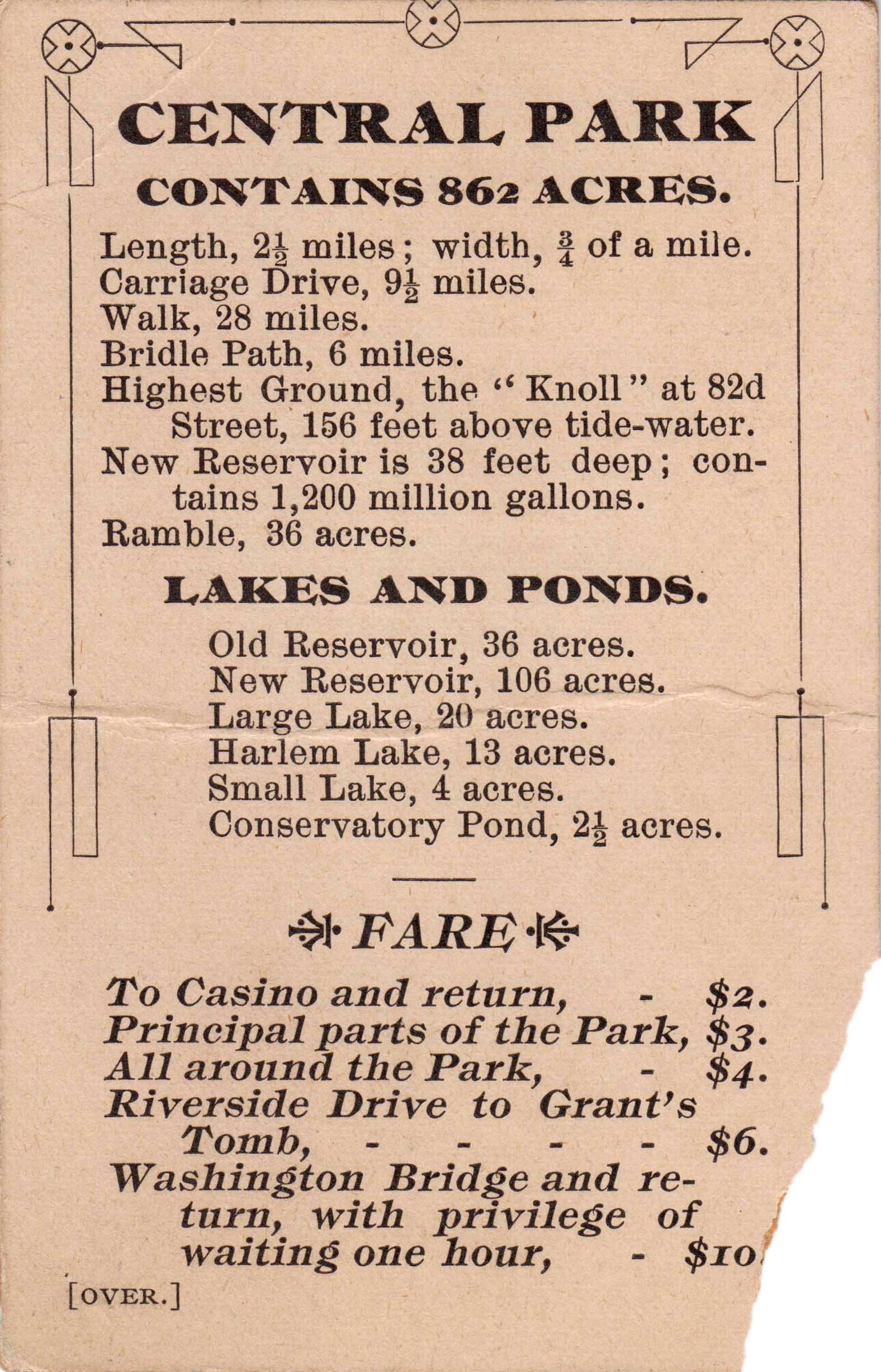

Central Park carriage ride card, n.d. Mayor James Walker collection. NYC Municipal Archives.

Central Park carriage ride card, n.d. Office of the Mayor, Jimmy Walker, NYC Municipal Archives.

Now owned by the city, the buildings became the park headquarters, and at one point the families of both Olmsted and Vaux lived at the site. With the outbreak of the Civil War, the US government took over the complex for use as a hospital for wounded soldiers who were, curiously enough, tended by the same Sisters of Charity who had previously owned the buildings!

Once it became known as a playground for drinking and dancing for the city’s elite, the Sisters of Charity asked that their name no longer be associated with the establishment. Renamed for the family most associated with the site, McGown’s Pass Tavern remained in operation until 1915, when its contents were put up for auction and the building torn down.

Drinking Fountains for Horses

Overlooking the Lake and just west of Bethesda Terrace is the peaceful area known as Cherry Hill, named for its spring-blooming cherry trees. The paved concourse on the crest of the hill was originally intended as a scenic turnaround for horse-drawn carriages, in the center of which was a stunning fountain for watering horses. Designed by Jacob Wrey Mould in 1867, it was constructed of polished granite, wrought iron and bronze, and decorative Minton tiles, with eight colorful porcelain saucers for birds to drink from.

Central Park, Drinking fountain for horses, southwest concourse, details of bronze finial and lamp, elevation, 1871. Jacob Wrey Mould, Architect. Department of Parks Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

Central Park, Drinking fountain for horses, southwest circle, details of bronze arm and porcelain saucer, 1871. Jacob Wrey Mould, Architect. Department of Parks Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals: Drinking fountain to be erected in Central Park, elevation, 1885. Jacob Wrey Mould, Architect. Department of Parks Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

The illustrations in this article, and more than 250 others, such as the original winning competition entry submitted by Olmsted and Vaux, meticulously detailed plans and elevations of many of the architectural features of the park, as well as intricate engineering drawings are included in “The Central Park: Original Designs for New York’s Greatest Treasure.” It is available at bookstores throughout the city and through on-line retailers.

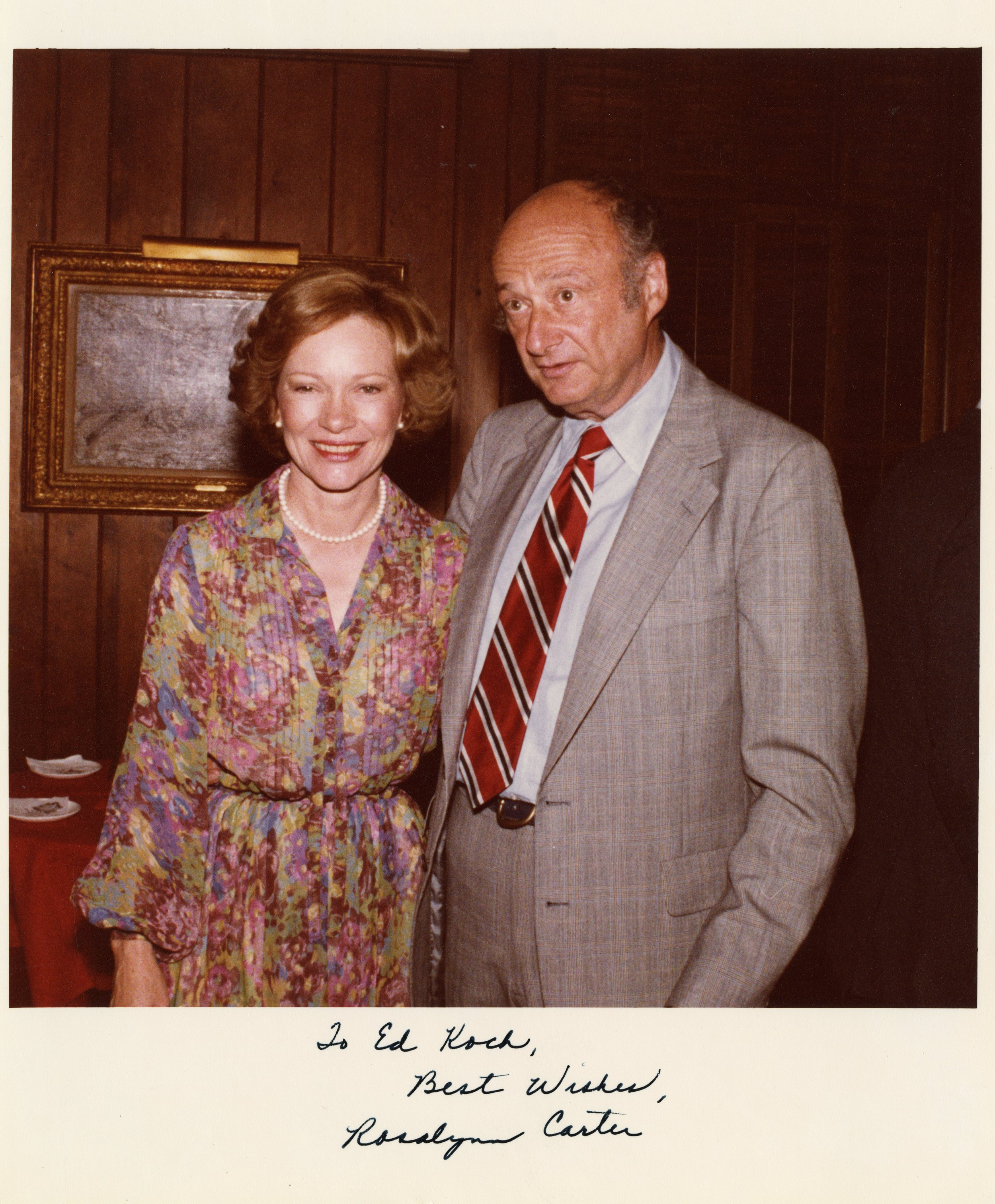

Mayor Edward I. Koch with First Lady Rosalynn Carter, 1979. Mayor Edward I. Koch collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

Following her death on November 19, 2023, many news stories, obituaries, and reminiscences about former first lady Rosalynn Carter remarked on her exceptional role as confidant and advisor to Jimmy Carter throughout their more than seven decades of married life. “Serving as an equal partner to her husband, the president,” wrote New York Times reporter Azadeh Moaveni, “. . . she frequently attended Mr. Carter’s cabinet meetings and traveled abroad to meet with heads of state in visits labeled substantive, not ceremonial. She often sat in on the daily National Security Council briefings held for the President and senior staff.” [“Before Hillary Clinton, There Was Rosalynn Carter.” November 21, 2023.] Given her important role it should not be a surprise that there are photographs of Rosalynn Carter in the Mayor Koch photograph collection in the Municipal Archives.

(L-R) First Lady Rosalynn Carter, New York State Governor Hugh Carey, President Jimmy Carter, Mayor Edward I. Koch, Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan, House Speaker Tip O’Neil, Treasury Secretary W. Michael Blumenthal, and Representative Mario Biaggi, August 8, 1978. Mayor Edward I. Koch photograph collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

On a hot summer day, President Jimmy and First Lady Rosalynn Carter stood before a cheering crowd in front of City Hall after a bill-signing ceremony that gave New York City $1.65 billion in Federal loan guarantees as part of the effort to avoid bankruptcy. The Times story reporting on the event noted that “Mr. Carter signed the measure on a mahogany desk that had been used by George Washington when he was President, and as Mr. Carter pointed out, New York was the nation’s capital and Washington was a swamp.” [“Carter Signs Aid Bill for New York at Gala Celebration at City Hall,” August 9, 1978.]

(Left to Right) Maureen Connelly (Press Secretary to Mayor Koch), President Jimmy Carter, First Lady Rosalynn Carter, and Mayor Edward I. Koch, Washington, D.C., June 1979. Mayor Edward I. Koch collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

Letter to Mayor Koch from Jack H. Watson, Jr., at the time, Assistant to the President for Intergovernmental Affairs, but who would become White House Chief of Staff to President Carter, August 14, 1979. Mayor Edward I. Koch Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

Joan Mondale, Vice President Walter Mondale, President Jimmy Carter, First Lady Rosalynn Carter, Amy Carter, and Senator Ted Kennedy, on the stage at the Democratic National Convention, Madison Square Garden, New York City, August 1980. Mayor Edward I. Koch photograph collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

Smiling faces on the dais belie drama behind the scenes. Earlier that summer, Mayor Koch’s request for additional federal support from the Carter Administration had not achieved the desired result. The President’s attempt to rescue the fifty-two Americans held hostage in Iran had stalled, and Senator Ted Kennedy’s presidential-run threatened to upend the convention. In the end, Carter prevailed, won the nomination, but lost to Ronald Reagan in the general election.

Correspondence, Jimmy Carter to Mayor Edward I. Koch, May 16, 1984 on behalf of Habitat for Humanity, regarding a building at 742-44 East 6th Street. Mayor Edward I. Koch Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

Correspondence, Mayor Edward I. Koch to Jimmy Carter, June 18, 1984, regarding the building at 742-44 East 6th Street. Mayor Edward I. Koch Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter continued their close collaboration during their post-White House years. The Habitat for Humanity organization was one of their most enduring endeavors. In 1984, they wrote to Mayor Koch and asked for his assistance with their work to rehabilitate a building on the Lower East Side of Manhattan.

President Jimmy Carter with Commissioner Anthony Gliedman of HPD, at a Habitat for Humanity project at 742 East 6th Street, Manhattan, July 1985. Photographer Leonard Boykin, HPD Photograph Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

Commissioner Anthony Gliedman of HPD, talking to Rosalynn Carter at a Habitat for Humanity project at 742 East 6th Street, Manhattan, July 1985. Photographer Leonard Boykin, HPD Photograph Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

The first Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade was held in 1924 with a parade of store employees and live zoo animals. Balloons were introduced to the parade in 1927. Here is a selection of photos taken by former staff member Ryan Rahman of the 2016 parade.

Have a happy and safe Thanksgiving!

Charlie, Kit and C.J., Macy’s Holiday Elves

Angry Birds’ Red

Pikachu from Pokémon

Eruptor from Skylanders

SpongeBob SquarePants

Thomas the Tank Engine

Wiggleworm

On April 12, 1988, New York City Mayor Edward Koch issued a press release announcing plans for the Museum of the American Indian to relocate its exhibition space from Audubon Terrace in upper Manhattan to the U.S. Custom House at Bowling Green in lower Manhattan.

Brochure, Museum of the American Indian, n.d. NYC Municipal Library.

The press release followed more than a decade of competing proposals and schemes to save the faltering museum. Although the final agreement transferred a significant portion of the holdings to a new National Museum of the American Indian in Washington, D.C., under the aegis of the Smithsonian, it gave the collection a significant presence in New York as a branch of the new Museum, formally known as the George Gustav Heye Center.

In recognition of Native American Heritage Month, For the Record looks at resources in the Municipal Archives and Municipal Library that tell the story of how Mayor Koch and other leaders kept an important cultural institution in the City.

George Gustav Heye, an engineer and financier, founded the Museum in 1916 to house objects he collected representing all the native peoples of the Americas. Also known as the Heye Foundation, the Museum of the American Indian (MAI) opened in 1922 on Audubon Terrace and West 155th Street in Harlem.

From the beginning, its distance from other cultural institutions in Manhattan curtailed attendance. Furthermore, the Audubon Terrace building was insufficient to display the holdings—less than one percent of the collection, according to some estimates. The bulk of the material was housed in a storage building in the Pelham Bay section of the Bronx.

By the 1970s, the MAI problems became critical. According to a clipping from the Daily News in the Municipal Library’s vertical file, dated February 16, 1975, the Museum “had been operating in the red since 1970.” The article quoted Museum Director Frederick Dockstader: “. . . unless the institution gets more space and more local support soon, it will probably leave.” Dockstader added: “When I first came to New York in 1960, I never realized how provincial New Yorkers really were. They live within a 20-block area and seldom venture beyond in search of cultural enlightenment.”

Museum of the American Indian, Audubon Terrace and West 155th Street, ca. 1940. Tax Photograph collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

By the mid-1980s, suffering further declines in attendance, the Museum took action on their plan to move from Audubon Terrace. To document this chapter in the saga, researchers can turn to the records of Mayor Edward Koch (1978-1989). Most mayoral record collections are arranged in three series: subject files, departmental correspondence, and general correspondence. However, there are variations unique to individual mayors. For example, Mayor LaGuardia filed his correspondence with federal officials as a separate series. Mayor Lindsay’s collection includes “confidential” subject files maintained as a separate series. Clerks filing Mayor Koch’s records merged his departmental correspondence and subject files into one series. Another unique feature of the Koch material, of great benefit to historians, is a subject and name index created by the archivists who processed his correspondence.

Searching the Koch inventory for references to the MAI resulted in five citations between 1985 and 1989. The first item is a New York Times article dated July 4, 1985, forwarded to Koch. Headlined “Indian Museum Shelves Negotiations with Perot,” the article quoted MAI officials saying they had suspended negotiations with H. Ross Perot, the Dallas computer executive seeking to relocate the museum to Texas. Instead they proposed to merge the museum with the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) in New York City.

In October 1985, Robert J. Vanni, Counsel at the Department of Cultural Affairs prepared and submitted a detailed report to Mayor Koch on the status of the MAI. In the “Historical Background” section of his report, Vanni pointed out that New York State Attorney General Louis Lefkowitz had brought a suit against the Museum board in 1975 for mismanagement. Under a consent decree the board was dissolved and the museum placed under direction of the Attorney General’s office. Vanni also described the proposed merger with the AMNH. Despite a pledge of $13 million from the City and State to underwrite construction of an addition to the AMNH along Central Park West, the MAI Board eventually rejected the idea, saying it would “terminate” their independence and would not provide sufficient space for the holdings. Vanni also reported on an alternative proposal that had been floated by New York Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan that would re-locate the Museum to the U.S. Custom House in Lower Manhattan.

The Library’s vertical files pick up the next phase of the saga. According to several articles in 1986, not all area political leaders supported the move to the Customs House, notably, New York’s other Senator, Alphonse D’Amato. “Absolutely not,” said D’Amato’s assistant Robin Salmon, when asked whether the senator would back to the move to the Custom House, according to a Daily News article dated August 15, 1986.

Negotiations continued through the next year. On July 17, 1987, the Daily News quoted Senator Moynihan saying that the city’s chance of keeping the MAI here is “slipping away” and urged support for his proposal to move the collection into the Custom House. He added that the Smithsonian Institution “wishes to abscond” to Washington with the “Indian treasure house.”

Two weeks later, reporter Gail Collins, then writing for the Daily News, neatly summarized the situation: “The real fight here is a matter of politics and prestige. Who gets to keep the stuff in the storehouse? Who will be blamed for losing the largest collection of American Indian artifacts in the universe?” (July 31, 1987.)

U.S. Custom House, Bowling Green, Manhattan, September 1, 1938, photographer: Suydam. WPA Federal Writers’ Project photograph collection. NYC Municipal Archives.

By mid-August 1987, it looked like the matter was settled. The New York Times headlined “Koch Shifts on New Site for Museum; Backs Custom House for Indian Exhibits.” According to the article, Mayor Koch and Senator D’Amato both said they had shifted their positions because of “concern that the museum might leave the city.”

Except, as the article continued, “Senator Daniel K. Inouye, chairman of the Senate Select Committee on Indian Affairs, proposed that the museum be moved to the nation’s capital and become affiliated with the Smithsonian Institution.”

Wrangling over the fate of the MAI and its collections continued into 1988. In January 1988, Mary Schmidt Campbell, the Commissioner of the Department of Cultural Affairs forwarded to Mayor Koch copies of letters she received from a dozen leaders of New York area cultural institutions including the Brooklyn Museum and the Guggenheim, all expressing support for the “Moynihan” plan and asking Senator Inouye to drop his opposition to maintaining the collection in New York.

Finally, in April 1988, political leaders reached a compromise and Mayor Koch issued his celebratory press release.

Mayor Rudolph Giuliani and guests at the opening of the National Museum of the American Indian, U.S. Custom House, October 27, 1994. Mayor Rudolph Giuliani photograph collection. NYC Municipal Archives.

The most recent clipping in the Municipal Library vertical file concludes the story: “A Heritage Reclaims – From Old Artifacts, American Indians Shape a New Museum.” The New York Times article reported on the opening of the New York branch of the National Museum of the American Indian, on October 30, 1994, at the newly renovated U.S. Custom House. As per terms of the final agreement there are three locations that house the collection: the George Gustav Heye Center in the Custom House, the National Museum of the American Indian on the mall in Washington, D.C., and a research center in Suitland, Maryland.

Look for future For the Record articles that highlight resources in the Municipal Archives and Municipal Library to explore topics related to Native Americans in New York City.