The Municipal Archives recently completed processing a significant portion of the New York Police Department Intelligence Unit records. Also known as the “Handschu” collection, the material totals 560 cubic feet and dates from 1930 to 2013. This exceptional material has already supported dozens of research projects. Processing and publication of the finding guide will expand its utility and encourage further exploration of important events and people during a significant period of American history. This week’s article will highlight the unusual origin of the collection and summarize series contents.

NYPD Intelligence Records, NYC Municipal Archives.

Most record collections are accessioned into the Municipal Archives in accordance with an official “retention schedule.” This document is created by DORIS record analysts. It specifies how long a series remains accessible to the record-creators in-house, and how long the records are maintained in an off-site storage facility (and retrieved by the record creators when needed). The schedule also indicates if the series has been designated as having long-term historical/archival value, and when it should be transferred to Municipal Archives for permanent preservation. If the record series does not have historical/archival value, it is disposed when it is no longer needed by the creating agency. Schedules are approved by the relevant agency Commissioner, DORIS Commissioner, and the Law Department.

Cassius Clay (Muhammad Ali) identification record, 1963. NYPD Intelligence Records, NYC Municipal Archives.

The Handschu collection, however, experienced a somewhat different trajectory to the Archives. The New York Police Department (NYPD) Intelligence Unit can be traced back to early decades of the twentieth century when police began investigating anarchists and other people and organizations thought to be a danger to public safety. During the 1950s, 60s and 70s, the NYPD Bureau of Special Services (BOSSI), called the Bureau of Special Services after 1971, investigated the Communist Party and organizations like the Black Panthers, Nation of Islam, and the Nazi Party. They monitored labor disputes, provided security detail for various dignitaries, secured information relating to political or social activities of individuals or groups seen as a threat, and cooperated with investigations conducted by the Immigration and Naturalization Services and other federal agencies. To support information gathering, the NYPD engaged in infiltration, wiretapping, and gathered information at events. Their tactics included overt and hidden photography, eavesdropping, and filming of various suspects and events.

In 1971, New York prosecutors tried members of the Black Panther Party for conspiring to blow up police stations and department stores. Evidence presented during the trial revealed the NYPD had infiltrated and kept dossiers on not only the Black Panthers but also on anti-war groups and other activists and civic organizations. The jury acquitted the Panthers after 90 minutes of deliberation.

Black Panther Party, free breakfast poster, n.d. NYPD Intelligence Records, NYC Municipal Archives.

Shortly after the acquittal, attorney Barbara Handschu, and others affiliated with various political organizations filed a lawsuit against the City of New York. The plaintiffs claimed that NYPD “informers and infiltrators provoked, solicited and induced members of lawful political and social groups to engage in unlawful activities.” They also alleged that the NYPD maintained files about “persons, places, and activities entirely unrelated to legitimate law enforcement purposes, such as those attending meetings of lawful organizations.” The case, known as Handschu v. Special Services Division was affirmed as a class action suit in 1979.

Environmental protest, 1967. NYPD Intelligence Records, NYC Municipal Archives.

In March 1985, federal judge Charles S. Haight, Jr. approved a settlement. It restricted surveillance of political activity by the NYPD. He agreed that surveillance of political activity violated constitutional protections of free speech. His ruling resulted in a consent decree which prohibited the NYPD from engaging “in any investigation of political activity except through the … Intelligence Division [of the Police Department]” and then only in response to suspected criminal activity. The decree required that any investigations shall be conducted only in accordance with the Guidelines incorporated into the Decree.

“Files” is the important word in the above narrative. In September 1989, Judge Haight appointed Joseph Settani, a certified records manager, and former DORIS staff member, to audit records created by the NYPD’s Intelligence Division. Settani identified the records by series and created a retention schedule that designated the material as having permanent historical/archival value. In accordance with that schedule, the NYPD transferred the records to DORIS' Municipal Records Center in 2008-2009. In further accordance to the schedule, the Municipal Archives accessioned the collection in 2015. Archivists conducted surveys of the series in 2016, and formal processing began the following year and continued until February 2024.

The New York Police Department Intelligence Unit records is comprised of two groups of similar records: (ACC-2015-022) New York Police Department Intelligence Unit records, circa 1930-1990, and (ACC-2018-014) New York Police Department Intelligence Unit records (“Handschu, part 2”), circa 1960-2013.

Subgroup 1 is arranged into ten series.

Columbia University, student protests, 1968. NYPD Intelligence Records, NYC Municipal Archives.

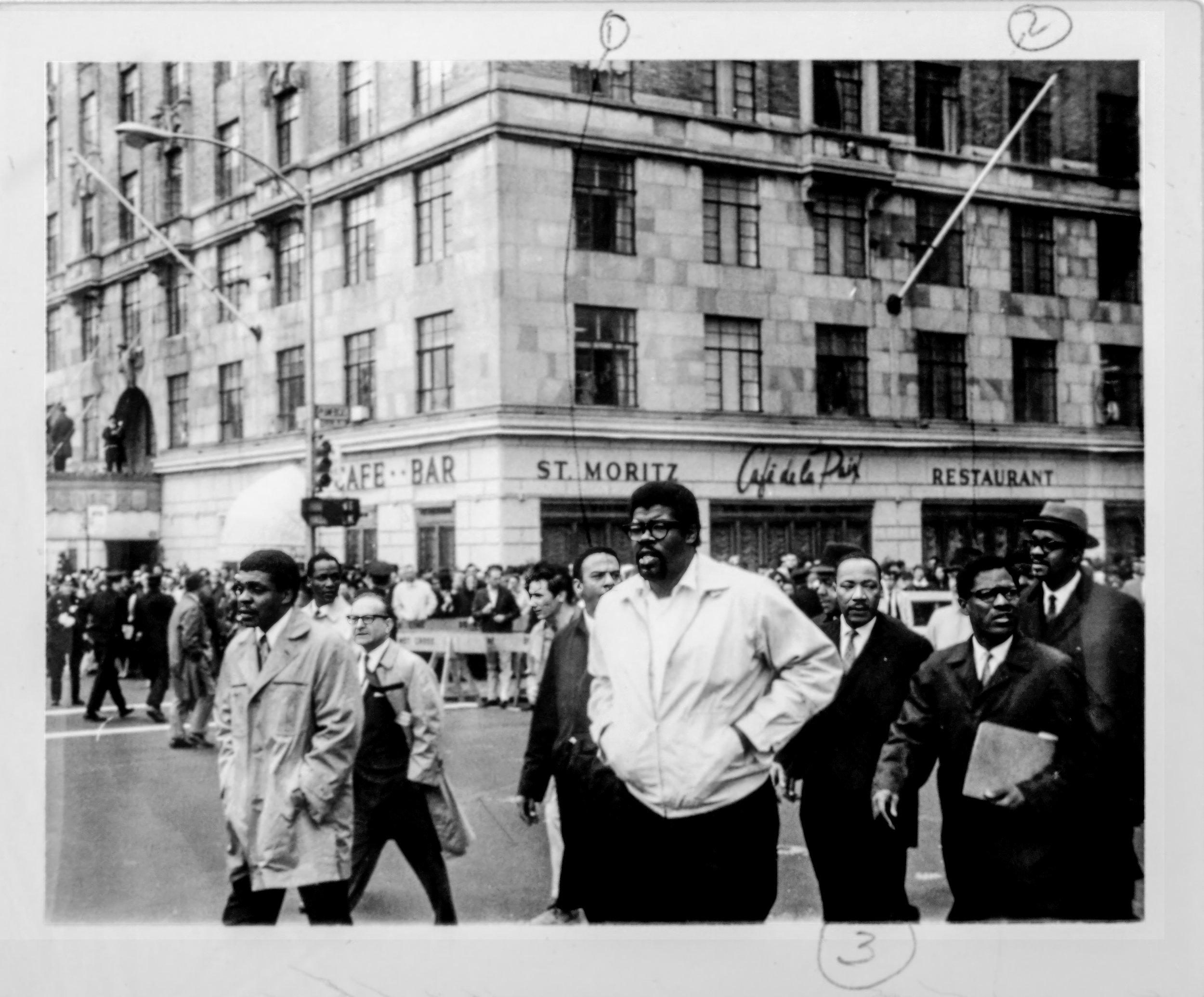

1.1 Photograph files, 1961-1972, 16 c.f. Surveillance images of events and demonstrations, including the Columbia University protests in 1968, the first Earth Day celebration in 1970, civil rights rallies, and anti-war demonstrations. It also includes images of foreign dignitaries' visits and surveillance taken during covert operations.

1.2 Numbered communication files, 1951-1972, 99 c.f.

Numbered police reports addressed to the police commissioner. The reports detail surveillance and investigation activities. The files contain both drafts and final reports.

1.3 Columbia University disturbance files, 1968-1970, 2.75 c.f.

Records related to the protests that took place at Columbia University during April and May 1968, including newspaper clippings, press releases, injury claims filed by students, letters received protesting police brutality, statistical data outlining arrests and injuries, and numerous photos and reports of areas affected by the protests.

1.4 Small organizations files, 1955-1973, 24. 5 c.f.

“Small Organizations” refers to the extent of material on a particular topic or organization rather than the size of that group.

1.5 Large organizations files, circa 1934-1990, bulk: 1955-1973

“Large Organizations” refers to the extent of material on a particular topic or organization rather than the size of the group. Organizations documented include the Black Panther Party, Nation of Islam, International Longshoremen’s Association (ILA), Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), and the East Coast Homophile Organization (ECHO). Events documented in this series include the Harlem “riots” of 1964 and the March on Washington (1963).

1.6 Individuals files, 1931-1973, 18.5 c.f.

Documents pertaining to national and international personalities, Hollywood celebrities, politicians, and activists. Types of materials range from newspaper clippings to extensive surveillance and wiretaps.

1.7 Hard Hat demonstration files, 1968-1970, 1981-1985, 11 c.f.

Hard Hat Riots, May 8, 1970. NYPD Intelligence Records, NYC Municipal Archives.

Records related to the May 8, 1970 riots in lower Manhattan during an anti-Vietnam War demonstration and memorial for the four students shot and killed at Kent State in Ohio. Consists of documents created in the months following the riots including reports, interviews, NYPD roll calls and rosters, forms, and newspaper clippings.

1.8 Index cards, 1960-1973, 200 c.f.

Index cards of people and organizations surveilled by NYPD between 1960-1973.

1.9 Binder master lists, 1986-1987, 11 c.f.

Binders contain name indexes of individuals, organizations, and events listed throughout the collection. The indexes were printed out on a dot matrix printer. There are three groups of binders; one group corresponds to Small Organizations Files otherwise known as Organization 1; Organization 2 corresponds to the Large Organizations Files; and the last grouping is a binder that serves as a master list for all organization names, photographs listed, and individuals in the collection. The indexes can include last name, first name, and page numbers the names are referenced in.

1.10 Audiovisual material, 1959-1971 3 c.f.

There are two subseries:1.10.1 includes a/v material maintained by the New York Police Department (NYPD); and 1.10.2 consists of items separated from other series in the collection and removed for reformatting and preservation.

Sister Marlane, candidate for governor of New York, 1969. NYPD Intelligence Records, NYC Municipal Archives.

The second subgroup, ACC-2018-014) has content similar to the first group, but date from a later time period, generally 1960 through about 2013. There is documentation on organizations such as Fuerzas Armadas de Liberación Nacional (FALN), Black Liberation Army (BLA), Jewish Defense League, Black Panther Party, Students for a Democratic Society, the Ku Klux Klan, and more. Many of the later records document the surveillance of Muslim individuals and communities in New York City. Other records concern surveillance of and NYPD preparation for significant events like the Republican National Convention (2004), Democratic National Convention (1992), the Presidential inauguration of George W. Bush, and the Million Youth March. There are also documents related to court cases concerning NYPD surveillance of private citizens and social/political organizations, including Raza v. City of New York (2013), the Matter of Fernandez v. The New York Police Department (2014), Handschu v. Special Services Division (1985), as well as the NYPD's role in the investigation, arrest, and federal criminal trial of Ahmad Wais Afzali. This material has not been processed.

For the Record has referenced the Handchu collection in several previous articles. Most recently, Finding Bayard Rustin, explored how records in the collection documented Rustin’s influence on some of the most successful demonstrations in civil rights history. Finding Marsha P. Johnson celebrated gay rights activist Marsha P. Johnson’s influence on New York City history using materials from Handschu. The Playboy Plot told the bizarre story of how Cuban Nationalists plotted to fire bazookas at the Playboy Club, based on records in the collection. NYPD Surveillance Films highlighted newly digitized film footage from the collection.

Researchers are encouraged to explore the newly processed materials.