For Veterans’ Day, we are highlighting an interesting group of glass lantern slides from the Queens Borough President collection. The slides are mostly scenes of soldiers working, relaxing, and playing at an army camp in a rural setting. In our online gallery they are simply listed as “Twenty-four views of mobilization camp or state militia camp, probably in Virginia, before or during Spanish-American War, ca. 1896-1898.” Why these images are in a collection of photographs created by the Queens Borough President Topographic Bureau was a complete mystery.

Soldiers in camp, 1898. James T. Chapman, photographer, Queens Borough President Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

Soldiers in camp, 1898. James T. Chapman, photographer, Queens Borough President Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

Soldiers in camp, 1898. James T. Chapman, photographer, Queens Borough President Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

Soldiers in camp, 1898. James T. Chapman, photographer, Queens Borough President Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

Initially, we surmised the images might be from Camp Wikoff, a quarantine camp established in Montauk, Long Island for troops returning from Cuba. As noted in a previous blog, disease, including typhoid, and yellow fever were endemic in Cuba, claiming the lives of more soldiers than died in battle. Concerned about spreading an epidemic in the United States, the army established Camp Wikoff to quarantine troops for several months before mustering out. The photographs of Camp Wikoff available online show a similar arrangement of tents and temporary wooden structures, but the Montauk site was barren, while our slides have a number of large trees in the background. In addition, two slides show troops in a downtown area with brick buildings. In one of these, soldiers pause in front of a pawn shop, behind them soldiers sit on the ledge of a building advertising “Fitzgerald-Photographer” and “S.N. Campbell-Sup’t-The Life Insurance Co. of Virginia.”

Soldiers in front of a pawn shop, possibly in Falls Church, Va., 1898. James T. Chapman, photographer, Queens Borough President Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

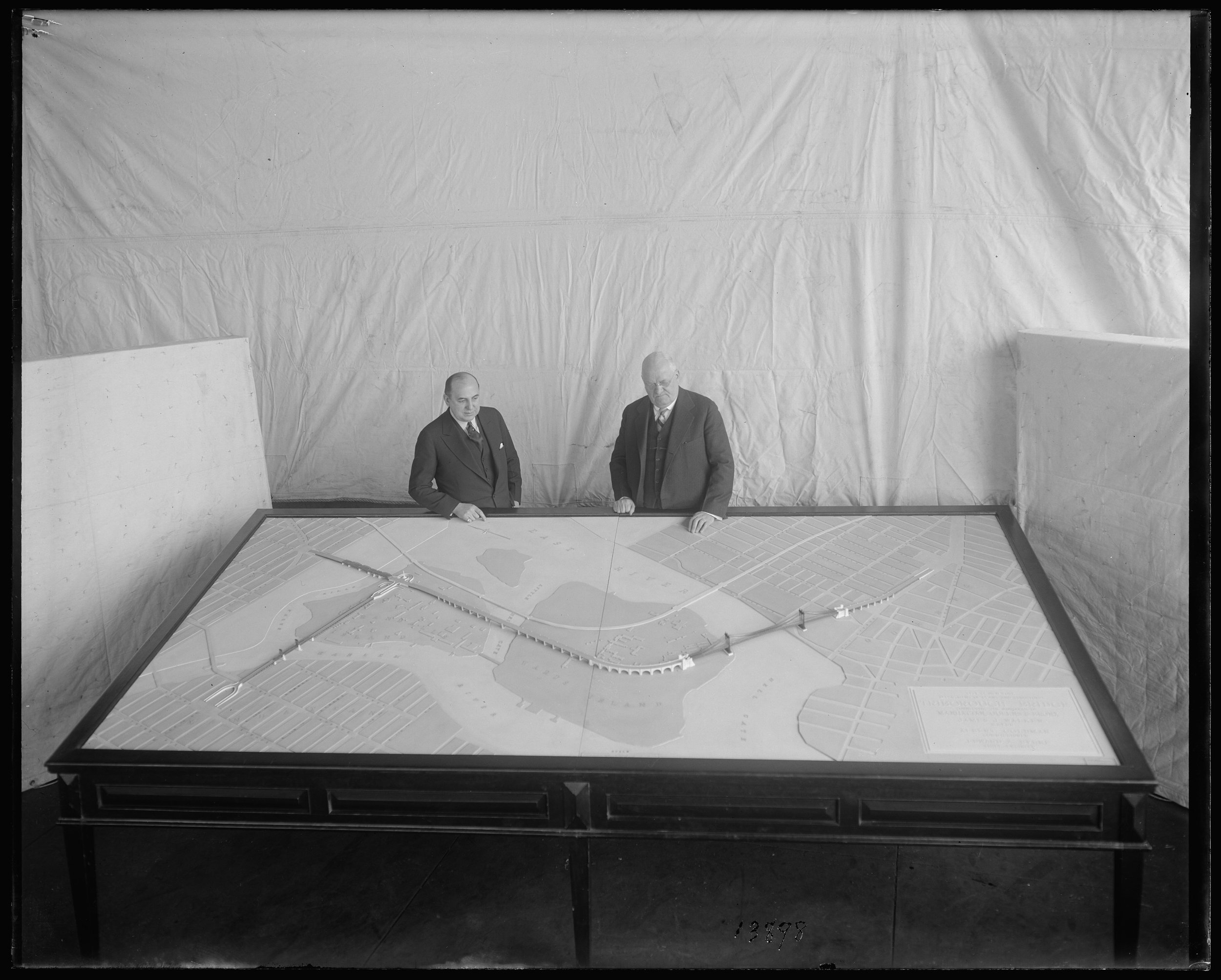

This is where the Virginia reference originated, but what were these images doing in the Queens collection? Looking at the original slides for more information yielded another clue. Glass lantern slides were made by projecting an original glass negative at another piece of glass coated with photographic emulsion. Once developed, the result would be a positive image. To protect the image from dust and fingerprints during projection, the emulsion was sandwiched between another piece of glass, often with a paper mask curved at the top edges. Sometimes these are generic, but in this case, we were lucky as the paper mask was decorative and personalized with the name “Jas. T. Chapman, Flushing, L.I.”

Soldiers blanket tossing at Camp Meade, Pa. 1898. James T. Chapman, photographer, Queens Borough President Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

Here was a Queens connection. But what was James T. Chapman of Flushing doing in Virginia and how did his photographs end up in this collection? Searches on Ancestry and in Queens City directories yielded a James Treadwell Chapman, listed variously as a clerk, or secretary, who died in 1901 of kidney disease. The personalized slide frames suggested a professional photographer or serious amateur, but no photographer by the name of Chapman was listed in the directories. However, as we discussed in a previous blog, camera clubs were very active in New York in the 1880 and ‘90s, and lantern slides were a common way for members to share their work at meetings. Chapman was not listed as a member of the New York Camera Club, but numerous other clubs existed in New York, including the Society of Amateur Photographers. Both clubs had regular “lantern slide test” nights when amateurs could project slides for review, and clubs exchanged slides with clubs in other cities, including those in Europe and Australia. Chapman was probably a sufficiently serious amateur that he had personalized frames made to ensure his slides would be returned to him after such exchanges.

Soldiers from Flushing at Camp Meade, 1898. James T. Chapman, photographer, Queens Borough President Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

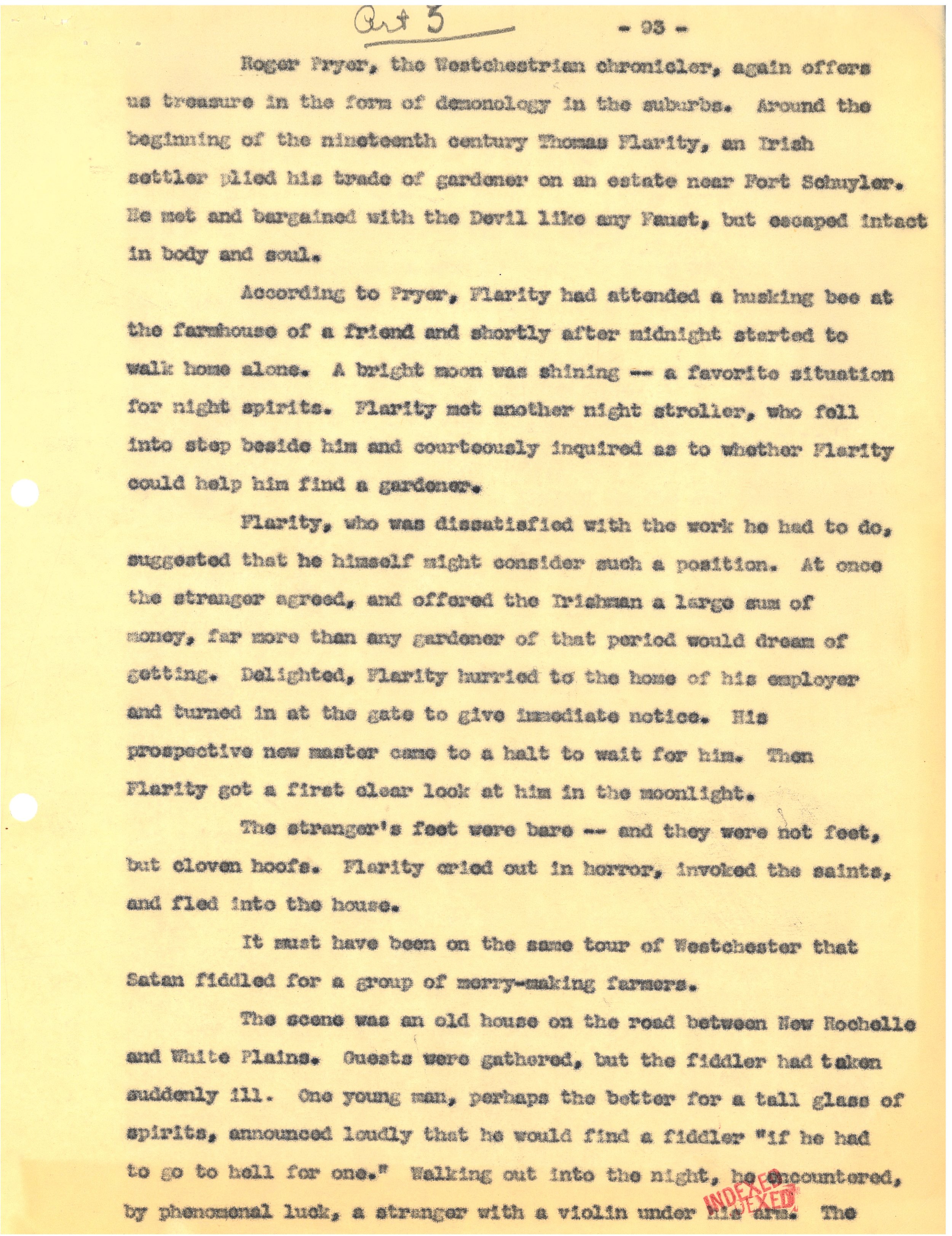

Another search in the Queens Borough President collection for “Chapman” revealed an additional image, from a small group of prints labeled “Chapman collection.” BPQ_03133-f shows a group of soldiers around an L sign. It is captioned: “Spanish-American War, Soldiers from Flushing at Camp Meade, 1898.”

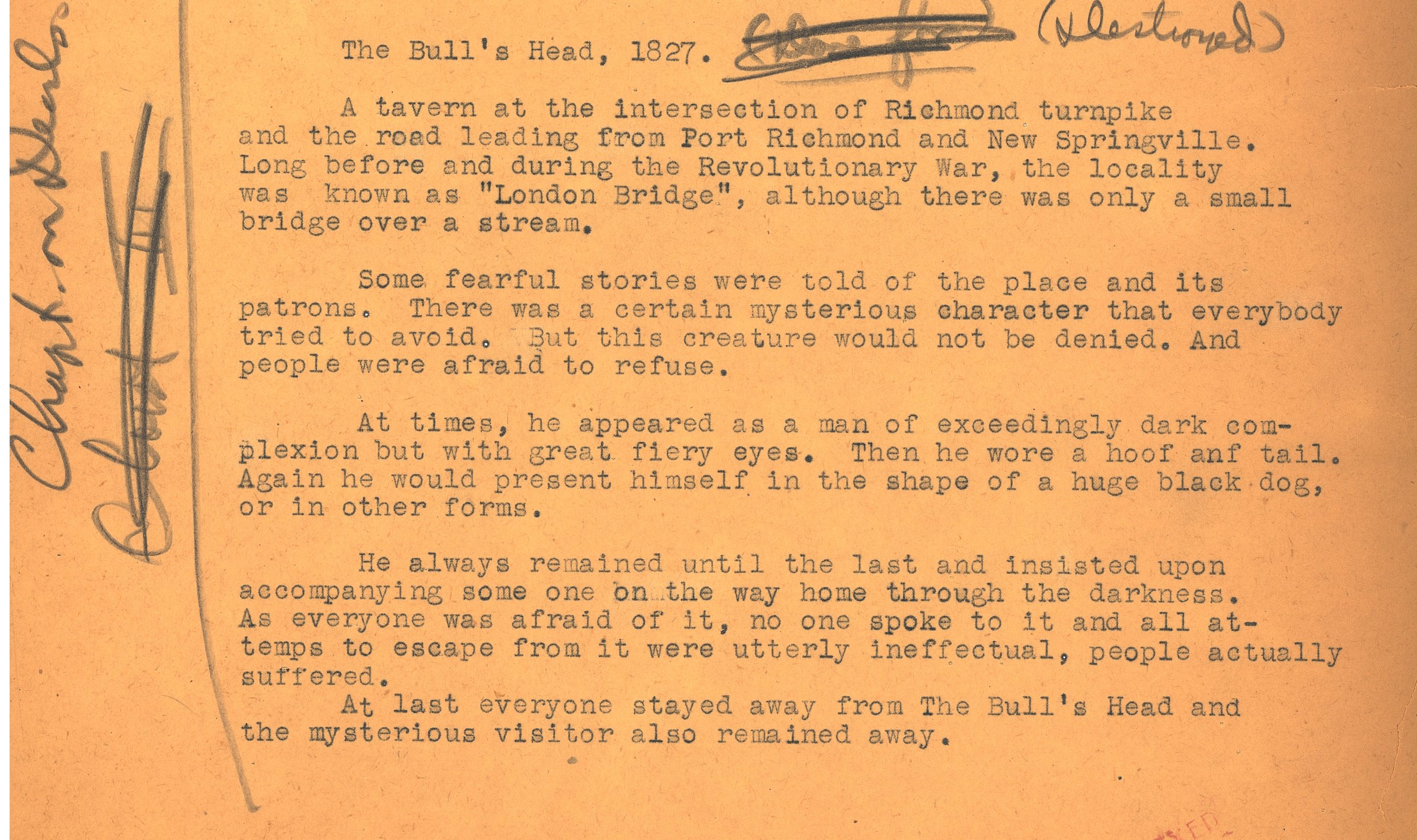

Camp Meade was established in August 1898, near Middletown, Pennsylvania, as a replacement for Camp Alger in northern Virginia, which was overrun with a typhoid fever epidemic. Camp Alger and Camp Meade were very much in the New York news in 1898, with the New York Times proclaiming on August 20, 1898: “Camp Meade Filling up; Thirty Thousand Men Are Expected in Ten Days and More Ground is Needed. Third New York’s Sick List Twelve Per Cent. of Its Men Confined to Their Quarters…” The article detailed recent deaths and the efforts to muster out troops scheduled to leave service. Adjunct General Tilinghast gave a press conference at the Waldorf-Astoria after returning to New York from a meeting with the Secretary of War, where he requested that “troops who had seen actual service, and those who have been in camp in localities where fever is prevalent, and those who for commercial reasons are most needed at home should be mustered out first.” He also mentioned that the 201st, the 202nd, and the 203rd NY regiments wished to remain in service. “These regiments are composed of very loyal men, who desire to remain soldiers as long as possible.”

African-American troops, 1898. The War Department encouraged recruitment of Black regiments as they believed they would be immune to tropical diseases such as yellow fever. This may be the 9th Ohio Battalion, a segregated battalion of the Ohio National Guard led by Charles Young, which was stationed at Camp Alger and Camp Meade. James T. Chapman, photographer, Queens Borough President Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

Soldiers playing basketball at Camp Meade, 1898. Basketball, which was developed in 1891, was already popular by 1898, but the backboard was not introduced until 1906. James T. Chapman, photographer, Queens Borough President Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

Families visiting soldiers at Camp Meade, 1898. James T. Chapman, photographer, Queens Borough President Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

The Times followed up on August 26th with an article “Review by the President, Troops at Camp Meade will March Past Him Tomorrow.” And on September 13th, they wrote that the “Third New York Quits Camp Meade.” However, on October 5th they published a new article, “Sick New York Troops at Camp Meade.” They reported that “Major Shakespeare of Philadelphia is making a study of the outbreak of typhoid among the New York regiments at Camp Meade…. The Two Hundred and Third New York has 400 cases of typhoid fever and is still isolated in the Conewago Hills, eight miles from the other troops.” The Surgeon General’s commission, which also included Major Walter Reed, eventually produced a “Report on the Origin and Spread of Typhoid Fever in U.S. Military Camps During the Spanish War of 1898.” At 2600 pages long, it was a landmark in modern medicine and led to reforms throughout the Army and national medical systems. The 203rd would remain in additional quarantine until November 12, 1898, when they left for a winter encampment in South Carolina. By November 18th, the Times reported “Camp Meade Now Wholly Deserted.” On December 10, 1898, the Spanish-American War ended with the Treaty of Paris and the 203rd never saw foreign service.

Soldiers at Camp Meade, 1898. James T. Chapman, photographer, Queens Borough President Collection, NYC Municipal Archives. On the back of the print, James W. Chapman is listed as 3rd from left, but it is unclear if that is standing or the leftmost seated figure.

One more thing, on October 29th, while the 203rd was still quarantined at Conewago, a young corporeal from Company F of Flushing, New York was promoted to sergeant. His name was James W. Chapman, James T. Chapman’s 21-year-old son. It seems that Chapman was able to visit his son at least once and take these photographs of the camp, and it is likely that the views of the downtown area are from Falls Church, Virginia when they were at Camp Alger earlier in the year. How these images came to be in the Queens Borough President’s collection is still a mystery, but there is another clue. Image 3133-k is entitled “Flushing Village Trustees – 1887” and with the print there is a typed slip of paper identifying the trustees, including one James Chapman.

Flushing Village Trustees Outing near the Flushing Water Works Station, 1887. James Chapman is listed as #7 in the back row, but that position is open to interpretation. Photographer unknown, Queens Borough President Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

George Washington Centennial, Civic and Industrial Parade, April 29-May 1, 1889. James T. Chapman, photographer, Queens Borough President Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

There are no other references to the “Chapman Collection” amongst the negatives, although at least one glass negative in the collection is a view duplicated in one of his lantern slides of the 1889 Washington Centennial parade. (An April 1889 NY Times article revealed that members of the Society of Amateur Photographers were stocking up on plates to photograph the centennial). In the 35 lantern slides we can positively identify as Chapman’s there are a few other lovely images, some of which have appeared before in For the Record. A couple of his images are hand tinted. Many of his images have a military connection, including a series of plates showing the parade for Admiral Dewey after his 1899 return from the Philippines.

From the events depicted, we can tell that Chapman was active as a photographer from at least 1889 to 1899. As a relatively prominent figure in Flushing, he may have had dealings with the Borough President’s office, which formed in 1898 with the consolidation of the boroughs. Perhaps after Chapman’s untimely death at age 48 in 1901 they were donated by his family. He had nine children, including his eldest son James, who not only survived the typhoid pandemics at Camp Alger and Camp Meade, he lived another 80 years, dying in the 1970s.

Calvary troops in formation near the Washington Bridge, probably preparing for the Admiral Dewey Parade, September 30, 1899. James T. Chapman, photographer, Queens Borough President Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

Admiral Dewey Parade, September 30, 1899. Admiral Dewey in cockaded tricorn salutes crowd. Mayor Van Wyck in top hat seated by him. James T. Chapman, photographer, Queens Borough President Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

West Point cadets, 7th Regiment marching in Admiral Dewey Parade, September 30, 1899. James T. Chapman, photographer, Queens Borough President Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

Hand-tinted lantern slide of a bicyclist in the woods, ca. 1890s. James T. Chapman, photographer, Queens Borough President Collection, NYC Municipal Archives. The bicycle fad and amateur photography developed simultaneously in the late 1800s.

A family at a Queens beach cottage, ca. 1898. James T. Chapman, photographer, Queens Borough President Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.