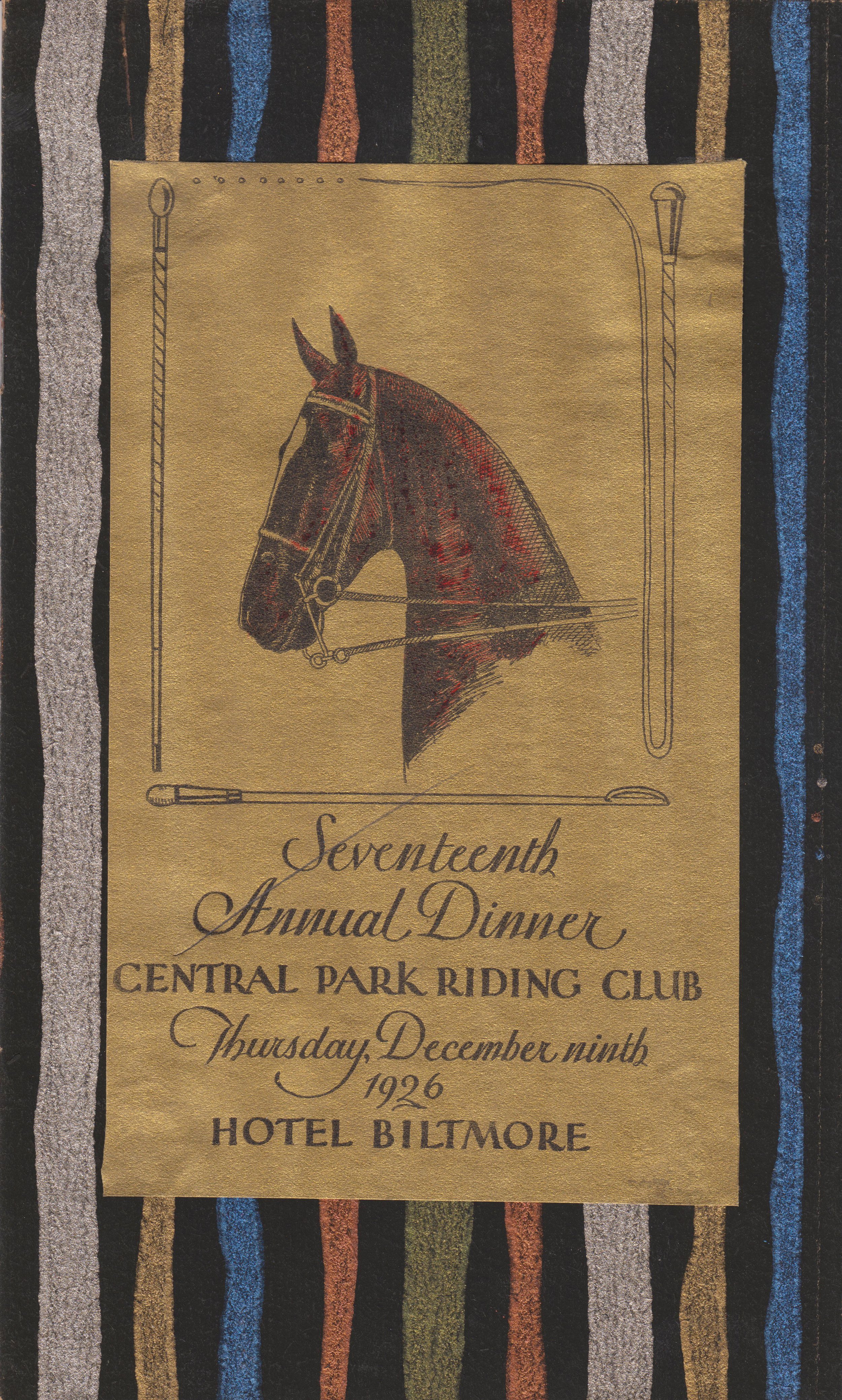

Central Park Riding Club dinner invitation, 1926. Office of the Mayor, Jimmy Walker, NYC Municipal Archives.

For more than one hundred fifty years visitors to New York’s Central Park have enjoyed picturesque vistas, rolling meadows, peaceful lakes, and a variety of charming architectural features.

Until recently, these pastoral scenes would have also included horseback riders cantering along the bridle paths. But after closure of the Claremont Riding Stables, located on Manhattan’s Upper West Side, in 2007, the horseback riders have largely vanished. Today—except for the southernmost area of the park where horse-drawn carriages still ply the roadway—horses are almost completely absent from the landscape.

A recent For the Record blog, Horsepower: The City and the Horse introduced the topic of the horse and its profound influence on virtually all aspects of city life. This week’s article looks at how the horse informed many of the design elements of Central Park.

Central Park, shelter for carriages and horses, preliminary study, front elevation, 1871. Jacob Wrey Mould, Architect. Department of Parks Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

Drives, Rides, and Walks

One of the most innovative features of Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux’ design for the park was their traffic circulation system that separated walkers, horseback riders, and horse-drawn carriages, creating intimate landscapes for each type of traveler.

The Drives were wide and sweeping, avoiding sharp turns to allow passengers in horse-drawn carriages to focus on the landscape. Park gardener Ignatz Pilat described the careful planning that went into their landscaping:

Central Park, Bridle Road Looking South, ca. 1913. Albert W. Schaad, photographer. NYC Municipal Archives collection. Schaad was a Central Park Zookeeper who created a scrapbook of his photos.

“The effect already produced and to be perfected in the course of time, throughout the length of the ‘Ride,’ is that of a pleasant country-road shaded by over-arching trees, mingled with shrubs and vines, spaces being left for more or less expanding views of open lawns, sheets of water, and other objects of interest which give the idea of extent and diversity; but wherever these open spaces would destroy the harmony of the landscape, a few scattered trees or low shrubs are so arranged as not to obstruct the view.”

The Rides, or bridle trails, generally hugged the perimeter of the park. For pedestrians, the Walks meandered through valleys, providing glimpses of the elegant carriage traffic nearby. All routes were surfaced and drained for safe passage in all types of weather. Where arteries met, the over- and underpasses of bridges were used as much as possible to separate carriage and horse traffic from pedestrians.

Central Park, Entrances and Gates, Entrance at 90th Street and Fifth Avenue, plan of entrance and section of adjoining wall, 1865. William H. Grant, engineer. Department of Parks Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

Another prescient feature of Olmsted and Vaux’ design for the park, also conceived to accommodate the horse, specifically horse-drawn vehicles, were the transverse roads. The original design competition specified that each submission must include at least “four or more crossing from east to west be made between Fifty-ninth and One Hundred and Sixth Street.” Olmsted and Vaux’ ingenious scheme was to sink the roads below grade. This made it possible to keep park visitors safely above the crosstown traffic, colorfully portrayed in their proposal as “coal carts and butchers’ carts, dust carts, dung carts” and “fire companies rushing their machines with fantastic zeal at every alarm.”

Winterdale Arch (Bridge No. 17)

Winterdale Arch, located along the West Drive near Eighty-Second Street, is named for its location on the Winter Drive, between Seventy-Second Street and 102nd Street. When planning the west side of the park, Olmsted and Vaux intended for this section to be planted with a variety of evergreens, to add color throughout the winter for carriage- and sleigh-riders.

Central Park, Bridge number 17 [Winterdale Arch], elevation of bridge and railing, 1861. Department of Parks Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

Stables and Workshops

After years of maintaining offices at Mount St. Vincent and the Arsenal, in 1869 the Central Park Board of Commissioners decided to construct “offices of Park administration” at a location that would be more easily accessible from all points in the park. The site proposed was at the northern edge of the old Yorkville Receiving Reservoir, on a sliver of land at a curve in Transverse Road No. 3, now called the Eighty-Sixth Street Transverse. The new offices would have included “engineering, architectural, and gardening apartments,” a stable with storage sheds for vehicles and machinery, and a separate building to house blacksmiths, carpenters, and other craftspeople.

Central Park, Offices of Administration, North Wing - East End, Details of Stable Building, Keeper’s Dwelling, etc. south front and west side elevations and longitudinal sections, 1869. Attributed to Jacob Wrey Mould, Architect. Department of Parks Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

Central Park, Offices of Administration, North Wing - East End, Details of Stable Building, Keeper’s Dwelling, etc. [detail], 1869. Jacob Wrey Mould, Architect. Department of Parks Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

Central Park, Offices of Administration, General Ground Plan of East End of North Wing, showing stable, sheds, yard and keeper's dwelling [detail], 1869. Attributed to Jacob Wrey Mould, Architect. Department of Parks Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

Mount St. Vincent/McGown’s Pass Tavern

In the latter part of the nineteenth century, a favorite stop for park visitors was the Mount St. Vincent Hotel. Built in 1881, it proved to be immediately popular with affluent New Yorkers, as the New York Times reported in 1886: “No matter how fast the team nor how elegant the equipage a turn ‘on the road’ is not done in proper shape unless it includes a bite or a sip in the Mount St. Vincent.

The Hotel was located in the quiet and rustic northeastern corner of the park, a landscape filled with steep bluffs and rough terrain. The old Boston Post Road—the original mail-delivery route from New York City to Boston—meandered between two rocky ridges in this area, and in the 1750s John Dyckman built a tavern to serve travelers in the vicinity of 105th Street and Fifth Avenue. Not long after, the McGown family purchased the land and tavern, running it successfully through the Revolutionary War. Hence the name of the small valley: McGown’s Pass.

Central Park, Mount Saint Vincent, design for a refreshment house, front elevation and side elevations, 1883. Julius F. Munckwitz, Architect. Department of Parks Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

The McGowns held the property until 1845, when they deeded the land and buildings to the Sisters of Charity of St. Vincent de Paul, who renamed the area Mount St. Vincent’s. Within a few years, the nuns had established a convent and school. To the existing structures, they added a two-story residence for the chaplain and a stately brick convent house that contained a beautiful chapel and large dining rooms. In 1856, before the nuns had consecrated their new chapel, they received word that the city would be taking their land for the creation of the new park.

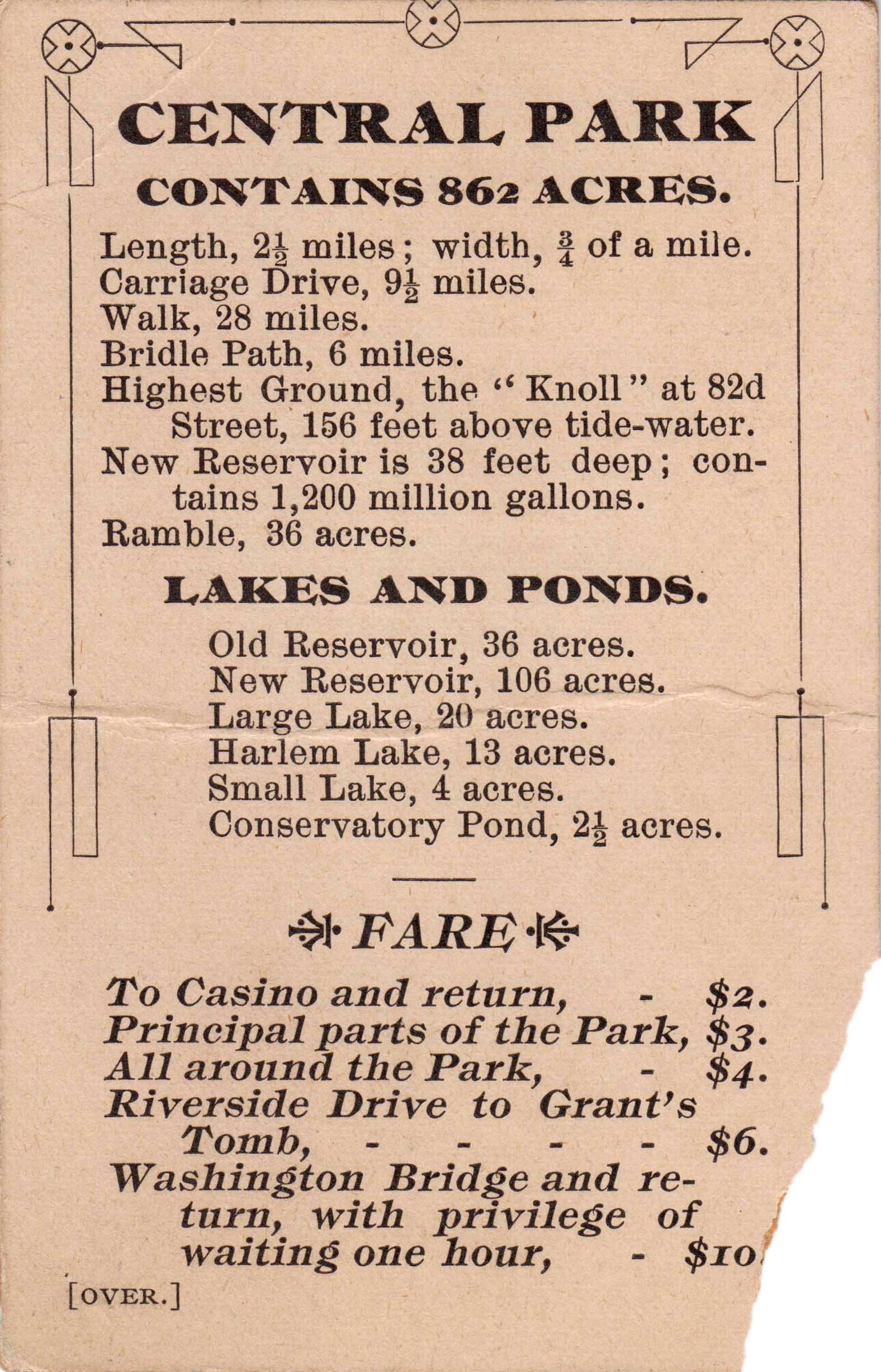

Central Park carriage ride card, n.d. Mayor James Walker collection. NYC Municipal Archives.

Central Park carriage ride card, n.d. Office of the Mayor, Jimmy Walker, NYC Municipal Archives.

Now owned by the city, the buildings became the park headquarters, and at one point the families of both Olmsted and Vaux lived at the site. With the outbreak of the Civil War, the US government took over the complex for use as a hospital for wounded soldiers who were, curiously enough, tended by the same Sisters of Charity who had previously owned the buildings!

Once it became known as a playground for drinking and dancing for the city’s elite, the Sisters of Charity asked that their name no longer be associated with the establishment. Renamed for the family most associated with the site, McGown’s Pass Tavern remained in operation until 1915, when its contents were put up for auction and the building torn down.

Drinking Fountains for Horses

Overlooking the Lake and just west of Bethesda Terrace is the peaceful area known as Cherry Hill, named for its spring-blooming cherry trees. The paved concourse on the crest of the hill was originally intended as a scenic turnaround for horse-drawn carriages, in the center of which was a stunning fountain for watering horses. Designed by Jacob Wrey Mould in 1867, it was constructed of polished granite, wrought iron and bronze, and decorative Minton tiles, with eight colorful porcelain saucers for birds to drink from.

Central Park, Drinking fountain for horses, southwest concourse, details of bronze finial and lamp, elevation, 1871. Jacob Wrey Mould, Architect. Department of Parks Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

Central Park, Drinking fountain for horses, southwest circle, details of bronze arm and porcelain saucer, 1871. Jacob Wrey Mould, Architect. Department of Parks Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

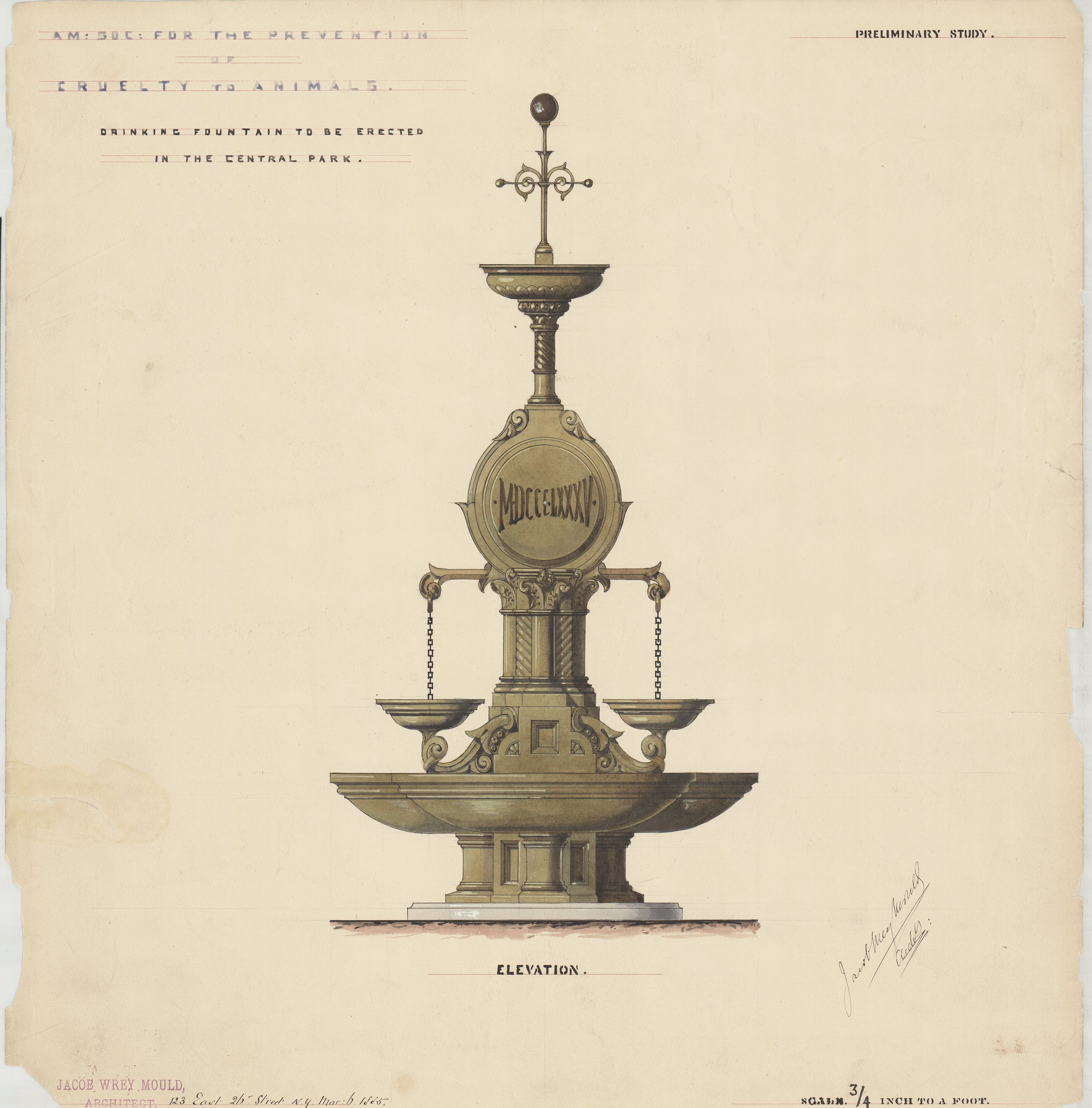

American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals: Drinking fountain to be erected in Central Park, elevation, 1885. Jacob Wrey Mould, Architect. Department of Parks Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

The illustrations in this article, and more than 250 others, such as the original winning competition entry submitted by Olmsted and Vaux, meticulously detailed plans and elevations of many of the architectural features of the park, as well as intricate engineering drawings are included in “The Central Park: Original Designs for New York’s Greatest Treasure.” It is available at bookstores throughout the city and through on-line retailers.