The Western Union Telegraph Company Building, 60 Hudson Street, Perspective of Hudson & Thomas Streets, May 29, 1928. New Building application 278 of 1928. Architects: Voorhees, Gmelin & Walker. Department of Buildings - Manhattan Block and Lot Collection, Block 144, Lot 33-56. NYC Municipal Archives.

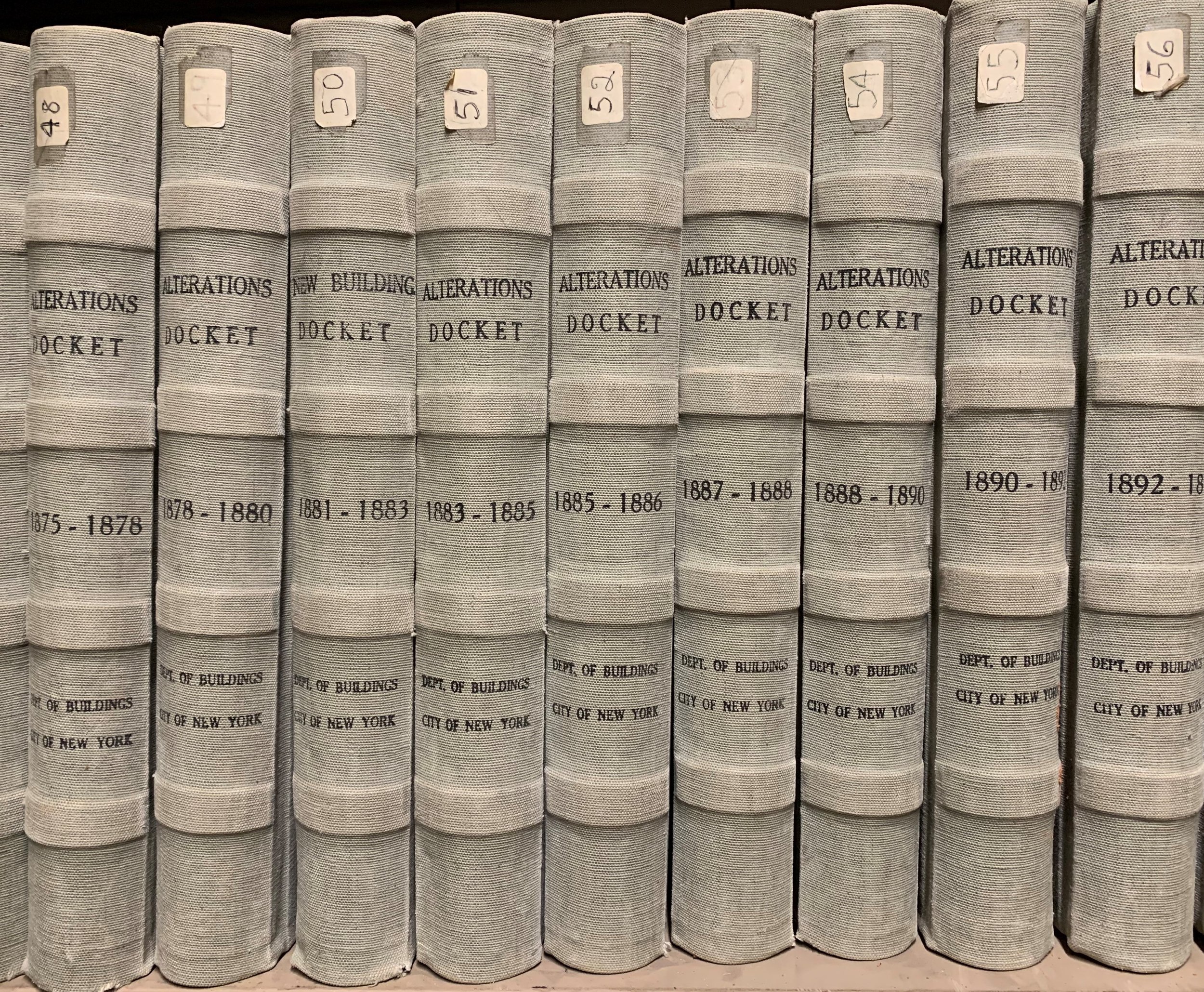

For the researcher investigating the built environment of New York City, material contained within the Municipal Archives is a gold mine. Recent blogs have described three of these resources, the Assessed Valuation Real Estate Ledgers, the Manhattan Department of Buildings docket books, and the Manhattan building plan collection, part 1, and part 2.

This week’s subject is another series from the Department of Buildings Record Group (025)—the application permit folders, a.k.a. the block and lot folders. The series is a subset of the Department of Buildings Manhattan Building Plan Collection, 1866-1977 (REC 074).

Totaling approximately 1,230 cubic feet, the permit folders provide essential and detailed construction and alteration information for almost every building in lower Manhattan from the Battery to 34th Street. In addition, a wide range of historical subjects can be explored using these records including the effect of planning, zoning and technology on building design, the role of real estate development as a gauge of national economic trends, and the evolution of architectural practice, particularly during the period of professionalization in the latter part of the 19th century.

Established in 1862, the Department of Buildings (DOB) “had full power, in passing upon any question relative to the mode, manner of construction or materials to be used in the erection, alteration or repair of any building in the City of New York.” All DOB personnel were required to be architects, masons, or house carpenters. Then, beginning in 1866, New York City law required that an application, including plans, be submitted to the DOB for approval before a building could be constructed or altered.

The provenance of the collection in the Municipal Archives dates to the 1970s when the DOB began microfilming the application files and plans as a space-saving measure. They intended to dispose of the original materials after microfilming. The project began with records of buildings in lower Manhattan, proceeding northward to approximately 34th Street when it was discovered that the microfilm copies were illegible. The DOB abandoned the project and the original records were transferred to the Municipal Archives for permanent preservation and access.

NB Application 34 of 1890, page 1, for a “Nurse Building” to be appended to the Society of the New York Hospital at 6 West 16th Street. Architect: R. Maynicke for George B. Post. Department of Buildings—Manhattan Block and Lot Collection, Block 817, Lot 29. NYC Municipal Archives.

NB Application 34 of 1890, page 2, for a “Nurse Building” to be appended to the Society of the New York Hospital at 6 West 16th Street. Architect: R. Maynicke for George B. Post. Department of Buildings—Manhattan Block and Lot Collection, Block 817, Lot 29. NYC Municipal Archives.

Most applications are accompanied by a site plan showing the building’s location. Site plan for the “Nurse Building” at 6 West 16th Street. NB Application 34 of 1890. Department of Buildings—Manhattan Block and Lot Collection, Block 817, Lot 29. NYC Municipal Archives.

New Building (NB) Applications

In theory, there should be an NB application for every building constructed after 1866. Unfortunately, prior to the mid-1960s, DOB policy was to dispose of the files of buildings that were demolished. The result is that the Municipal Archives collection generally comprises only records of buildings extant as of the mid-to-late 1970s.

The NB application provides the most complete and detailed information about a structure. The form includes location (street address and block and lot numbers); the owner, architect and/or contractors; dimensions and description of the site; dimensions of the proposed building; estimated cost; the type of building (loft, dwelling factory, tenement, office, etc.); and details of its construction such as materials to be used for the foundation, upper walls, roof and interior. Every NB application was assigned a number, beginning with number one for the first application filed on or after January 1, up to as many as 3,000 or more by December 31, each year.

Specifications form, front NB application 222 of 1919, the Cunard Building, 25 Broadway. Department of Buildings—Manhattan Block and Lot Collection, Block 13, Lot 27. NYC Municipal Archives.

Specifications form, reverse, NB application 222 of 1919, the Cunard Building, 25 Broadway. Department of Buildings—Manhattan Block and Lot Collection, Block 13, Lot 27. NYC Municipal Archives.

As buildings incorporated new technologies such as elevators and steel-frame construction, the approval process became more rigorous, requiring more extensive information about the proposed structure. Permit folders for larger buildings often contain voluminous back-and-forth correspondence between the DOB examiners and the owners and architects. If any part of an NB application was disapproved the owner or architect was obliged to file an “Amendment” form stating what changes would be made to the application so that the building would comply with building codes.

Amendment to NB Application 44 of 1925, filed November 23, 1926 for the building at 35 Wall Street. Each point on the amendment explains how the architects were modifying their plans to meet DOB objections. (Note point no. 4. “The height of the Wall Street front has been altered to meet the requirements of the Building Zone Resolution—Article 3, Section 8. All setbacks have been clearly noted on elevations and setback plan.)” Department of Buildings—Manhattan Block and Lot Collection, Block 26, Lot 1. NYC Municipal Archives.

Correspondence from the Commissioner of the Department of Public Works in the Office of the President of the Borough of Manhattan, to the Department of Buildings regarding NB application 222 of 1919 (the Cunard Building at 25 Broadway), and possible disruption to sewers and sidewalks, August 21, 1919. Department of Buildings—Manhattan Block and Lot Collection, Block 24, Lot 27. NYC Municipal Archives.

Correspondence from the Zoning Committee to the Department of Buildings regarding the height of the Cunard Building, 25 Broadway, NB application 222 of 1919. Department of Buildings—Manhattan Block and Lot Collection, Block 24, Lot 27. NYC Municipal Archives.

When the DOB approved a NB application, they issued a permit and construction could begin. Periodically during construction, inspections would be made by DOB personnel and their reports would also be included in the application file.

Other Applications

After a building was completed and the final inspection report submitted, any subsequent work on the building would require a separate Alteration (ALT) application. As building technology became more complex, the DOB began to require separate applications for elevator and dumbwaiter installations, plumbing and drainage work, certificates of occupancy and electric signs. The permit files also contain numerous Building Notice (BN) applications pertaining to relatively minor alterations. The DOB also mandated a “Demolition” application to raze buildings. The permit files generally do not include documents related to building violations.

DOB building permit folder, Block 551, Lot 21, 26 West 8th Street. Department of Buildings—Manhattan Block and Lot Collection. NYC Municipal Archives.

The DOB organized all applications and related correspondence into folders according to the block and lot where the building was situated. After 1898, each block in Manhattan was assigned a number, beginning with number 1 at the Battery, and each lot within the block was also assigned a number. The original block and lot filing scheme has been maintained by the Municipal Archives for the block and lot permit collection. An inventory of the permit folder collection is available in the new online Municipal Archives Collection Guides.

The Municipal Archives has also maintained the original permit folders, whenever possible. The folder lists the application paperwork contained within and serves as a table of contents. If paperwork related to an application listed on the folder is missing, it is possible to trace at least basic information about the action using the DOB docket books as described in a recent blog Manhattan Department of Buildings docket books.

American Exchange Irving Trust Company, to the DOB, December 28, 1928, regarding application to the Board of Standards and Appeals. NB application 419 of 1928. Irving Trust Company Building at One Wall Street. Department of Buildings—Manhattan Block and Lot Collection, Block 23, Lot 7. NYC Municipal Archives.

Application for Variation from the Requirements of the Building Zone Resolution filed by the American Exchange Irving Trust Company, for One Wall Street, NB application 419 of 1928. Department of Buildings —Manhattan Block and Lot Collection, Block 23, Lot 7. NYC Municipal Archives. (N.B. The variance was approved.)

Building bulk calculation diagram submitted with Application for Variation from the Requirements of the Building Zone Resolution filed by the American Exchange Irving Trust Company, for One Wall Street, NB application 419 of 1928. Department of Buildings—Manhattan Block and Lot Collection, Block 23, Lot 7. NYC Municipal Archives.

The collection provides detailed data about specific buildings and enables the researcher to explore broader topics. For example, one theme of interest to architectural historians is the impact of New York’s 1916 zoning ordinance. The regulation had been imposed partly in response to construction of the massive Equitable Building on lower Broadway, but more generally to reduce the growing density of the built environment. It is usually argued that the law was responsible for the setback style of New York skyscrapers constructed throughout the 1920s. In an examination of the NB applications for several skyscraper buildings erected before the Depression, such as the Irving Trust tower at 1 Wall Street, it was found that very often the original NB application was disapproved, in part because the building plans violated some part of the 1916 zoning ordinance. In response, however, the architects did not revise their plans, but instead appealed to the City for a variance and invariably received permission to proceed with their original plans.

Application to convert a stable to a sculptors studio, ALT 531 of 1903, no. 26 West 8th Street / 5 McDougall Alley. Department of Buildings—Manhattan Block and Lot Collection, Block 551, Lot 21. NYC Municipal Archives.

The permit folder collection also provides ample opportunity for researchers to study the long tradition of adaptive re-use of buildings in lower Manhattan. Although many of the buildings in these neighborhoods pre-date establishment of the DOB, the collection is rich with applications submitted for later alterations, as architects, homeowners, and developers converted older structures into “modern” dwellings by removing stoops and covering facades with light-colored stucco, mosaic tile, and shutters.

Correspondence from architect Cass Gilbert to DOB, September 22, 1905. NB application 1376 of 1905, 90 West Street Building. Manhattan Block and Lot Collection, Block 56, Lot 4. NYC Municipal Archives.

The permit folders, along with the associated building plans, contain documentation for the study of individual architects, as well as architecture as a profession. Scholars will find an abundance of unique materials that detail the professionalization of the field, especially during the latter half of the 19th century.

Together with the Assessed Valuation of Real Estate ledgers, the several Department of Buildings series—docket books, architectural plans, and the permit folders, provide an unparalleled opportunity for detailed research on the built environment. Few other cities in the nation possess a body of documents whose scope and completeness can compare with these New York City records.