A recent Bowery Boys podcast about the wall kindly directed listeners to my earlier blogs. However, one part of the story intrigued/stumped me. They reference an earlier wall built in 1644 near the end of Governor Kieft’s war with the native tribes. Was it possible that the wall really was built to defend against attacks by the natives and not the English? This blog explores that possibility and raises new avenues for exploration. The language quoted in these records obviously reflects the viewpoints of the Dutch colonial government. The Municipal Archives plans to add new content to New Amsterdam Stories by 2024 describing colonization from the perspectives of the original Munsee Lenape inhabitants and enslaved peoples to coincide with the 400th anniversary of Dutch settlement on Manhattan. These long over-due stories were originally planned when the website was launched, but the relocation of our offsite collections and COVID disrupted these plans.

The source for the 1644 wall claim is a Curbed New York article that references an article in Harper’s magazine “The Story of a Street,” from 1908, by Frederick Trevor Hill. In it, Hill wrote that on March 31, 1644, Kieft ordered a barrier to keep in stray cattle and defend against Native Americans. Hill was a lawyer and historian, and his enjoyable, but rather fanciful, article does get some things right, like this footnote:

“About this time (1655-6) the residents of Pearl Street, inconvenienced by the high tides, caused a sea wall to be erected, and the space between this barrier and their houses to be filled in, making a roadway known as De Waal, or Lang de Waal. Incautious investigators have confused this with Wall Street, and their error has resulted in some astonishing ‘history.’”

Very true. Since he was correct about this, his 1644 claim bears investigating. For the original source we need to go to records in the New York State Archives:

“31st of March [1644]

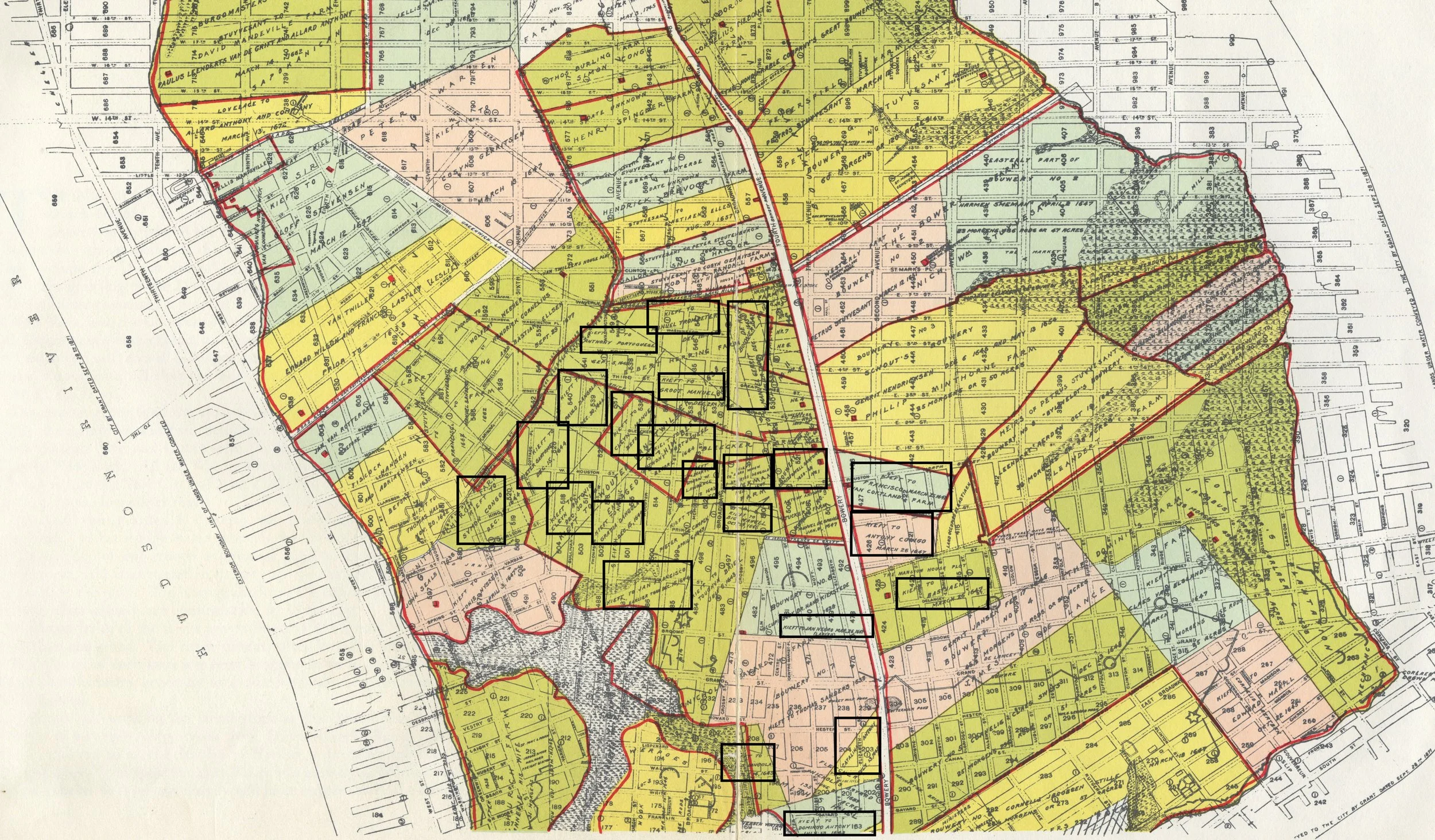

Whereas, the Indians, our enemies, daily commit much damage, both to men and cattle, and it is to be apprehended that all of the remaining cattle when it is driven out will be destroyed by them, and many Christians who daily might go out to look up the cattle will lose their lives; therefore, the director and council have resolved to construct a fence, palisade, or enclosure, beginning from the great bouwery to Emmanuel’s plantation. Everyone who owns cattle and shall desire to have them pastured within this enclosure is notified to repair there with tools next Monday morning, being the 4th of April, at 7 o’clock, in order to assist in constructing the said fence and in default thereof he shall be deprived of pasturing his cattle within the said enclosure.”[2]

Already the claim starts to fall apart, as what is described is a cattle pen not a defensive wall. The main concern seems to be that cattle would wander up-island when put out to pasture, which was dangerous for the cattle and for colonists who were in the woods looking for them. Earlier records scold colonists for letting their cattle trample the maize fields, which caused conflict with the Lenape and hurt the supply of grain for the colonists. Incidentally, the next two passages in the state records are notices of the peace treaties signaling the end of the war.

So not a wall, but where was this cattle fence? Hill thought it ran from “William Street… to what is now Broadway, and possibly from shore to shore, marked the farthest limits of New Amsterdam, as it then existed, and practically determined the location of Wall Street.”[3] Hill then went on to colorfully describe Stuyvesant in 1653 “stumping along the line of Kieft’s old cattle guard, seeking an advantageous location for the Palisade…” and placing it “some forty or fifty feet south of the old barrier and practically parallel to it….”[4]