The New York City Municipal Archives recently applied for funding to digitize colonial-era ledgers selected from the “Old Town” records collection. These unique administrative and legal records, dating from 1645 through the early 1800s, document the Dutch and English colonial settlements in New York City, western Long Island, and the lower Hudson Valley. The project is part of a larger Archives plan to describe and provide online access to all records in the Municipal Archives from the Dutch and English colonial era through early statehood.

The Archives has already successfully completed digitization and provided on-line access to the Dutch records of New Amsterdam and the proposed project will expand this effort to include the earliest records of communities throughout the metropolitan New York City region.

“The Court Book and nothing else to be found therein, 1751.” Newtown, Book 1, Old Town Records, NYC Municipal Archives.

The ledgers chosen for digitization are the earliest records in the Old Town records collection. These records were created by European colonists in communities throughout the New York City region. Commissioned by the Dutch East India Company, Henry Hudson led the expedition to what is now New York City in 1609. In 1614, the area between the Delaware and Connecticut Rivers was designated the colony of New Netherlands. Ten years later the States General of the Netherlands created the Dutch West India Company awarding them a monopoly on trade over a vast domain from West Africa to Newfoundland.

The first colonists in New Netherlands arrived in 1624 at Fort Orange (near Albany). In 1626 other settlers came to Manhattan Island and named their community New Amsterdam. As more colonists arrived they established new settlements resulting in an archipelago of Dutch communities throughout what is now Brooklyn, Queens, Richmond (Staten Island), and Westchester.

Dutch conflict with England over boundaries and trade led Charles II of England to grant the colony to his brother James, Duke of York, in March 1664. New Amsterdam surrendered to the English on September 8, 1664, and was renamed New York. Though in 1673, the Dutch briefly reclaimed the colony, the Treaty of Westminster returned it to English control in 1674.

Bushwick Deeds from 1660 and 1661 issued by Petrus Stuyvesant. Old Town Records, NYC Municipal Archives.

The provenance of the Old Town records collection dates from consolidation of the modern City of New York on January 1, 1898. Previously, the towns, villages and cities within the counties of Kings, Queens (parts of which are now in Nassau County), Richmond and Westchester (parts of which are now in Bronx County) maintained their own local governments that each created records—legislative, judicial, property, voter, health, school, etc. These local governments were dissolved during the latter part of the nineteenth century, at first by annexation to the old City of New York (Manhattan), or the City of Brooklyn, and finally through the unified City consisting of the five Boroughs in 1898.

The Comptroller of the newly consolidated city recognized the importance of the records of the formerly independent villages and towns and ordered transfer of the Queens, Richmond and Bronx/Westchester ledgers to the central office in Manhattan. In August 1942, fearing that New York City would be a prime target for enemy invasion, the Comptroller packed the ledger collection into crates and shipped them to New Hampton, N.Y. for the duration of the war. The Archives received the records from the Comptroller in several accessions from the 1960s to the 1990s.

The bulk of the Kings County town and village records were acquired by the Kings County Clerk via annexation during the latter part of the 19th century. Beginning in the 1940s, James A. Kelly, then Deputy County Clerk of Kings County arranged that the “historical” records of the county be turned over to St. Francis College in Brooklyn Heights, “on permanent loan.” They were housed in the James A. Kelly Institute for Historical Studies at the College. While in the custody of the Institute the ledgers were microfilmed. In 1988, due to financial considerations, the College closed the Institute and the records were transferred to the Municipal Archives.

Of particular note are the records of the Gravesend settlement in Kings County. Granted to Lady Deborah Moody in 1645, it became the only English town in the Dutch-dominated western area of Long Island. Based on the frequency in which her name appears in the Gravesend Town records, it is clear that Lady Moody, a religious dissenter who fled England and later Massachusetts, took an active and intense interest all aspects of her community.

Patent for the town of Gravesend, given to Lady Deborah Moody and her followers, 1645. Old Town Records, NYC Municipal Archives.

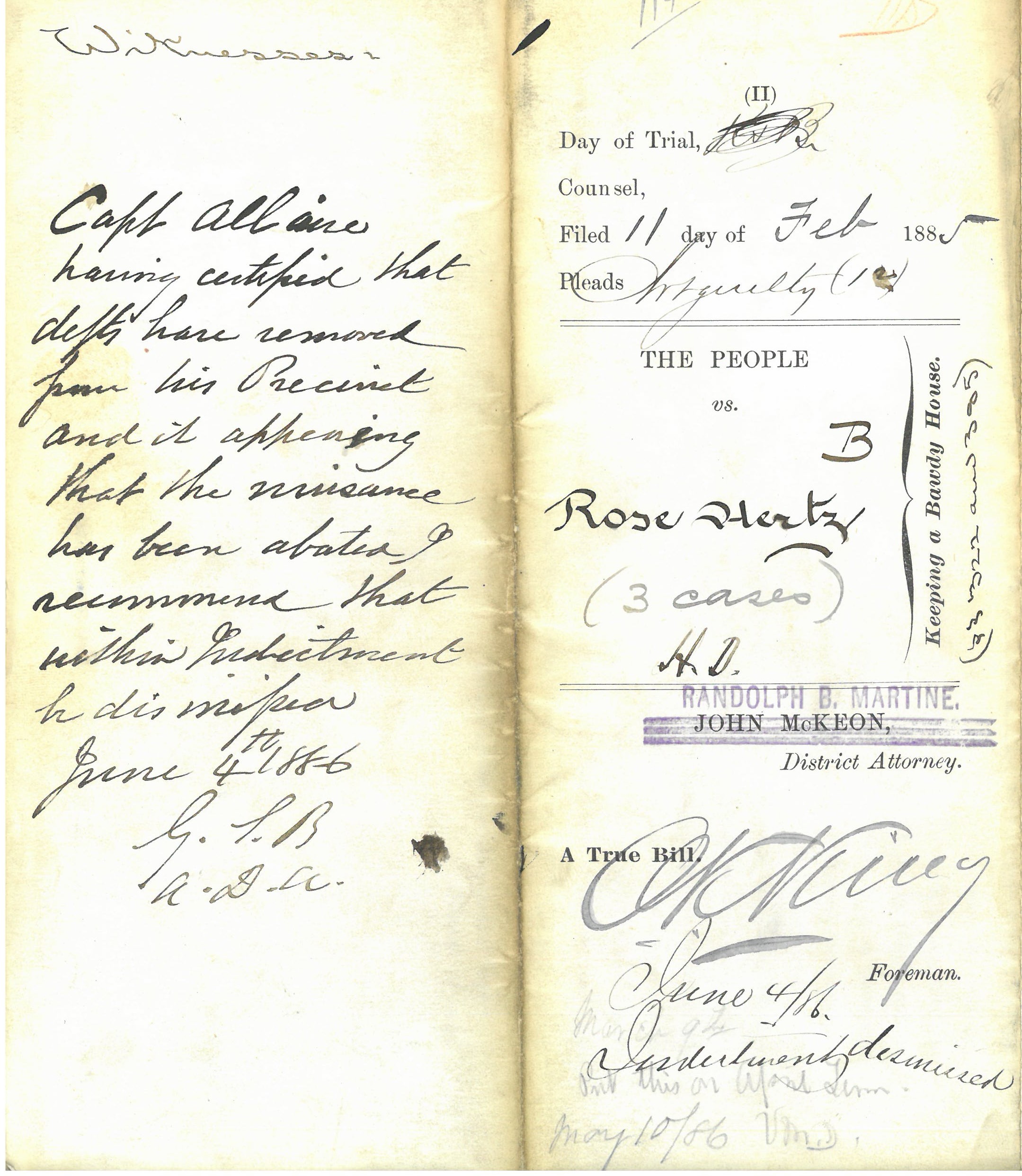

The Old Town records consist of hand-written manuscripts bound in a variety of styles (single-section pamphlets, spring-back account-book, and case-bound ledgers, among others). They include town and village governing board and legislative body proceedings and minutes, criminal and civil court docket books, deeds and property conveyances, records of estate administration, and coroners' records.

The earliest records are written in mid-17the century Dutch which differs from modern Dutch. The records from the English colonial period are written in a combination of old Dutch and English. The materials also include non-contemporary (19th Century) manuscript translations and/or transliterations of the Dutch records.

Several unique characteristics of the New Netherlands/New York colony make its records important for understanding the origins of the American democratic system. From its earliest years, the colony was notable for its diversity. Unlike New England and Pennsylvania where religion played the dominant role, the New Netherland colony was founded as a commercial enterprise. The official religious denomination of the colony was the Calvinism of the Reformed Church, but the Dutch West India Company urged tolerance toward non-Calvinists to encourage trade and immigration. Among the religious groups in New Netherlands (and more or less tolerated) were Lutherans, Quakers, Anabaptists, Catholics and Jews. The colony actively recruited immigrants from Germany, England, Scandinavia, and France, and was the home of the largest number of enslaved Africans north of Maryland.

“Register of the children born of slaves after the 2nd day of July 1799, within the town of Flatlands in Kings County in the State of New York…” Old Town Records, NYC Municipal Archives.

One recent example of the type of research that will be facilitated by the digitization work is the New York Slavery Records Index project underway at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice (City University of New York). Impetus from the project came from the realization that the college’s namesake, John Jay, and his family, were prominent slave-holders. The index project will result in a searchable compilation of records that identify individual enslaved persons and the slaveholders, beginning as early as 1619, and ending during the Civil War. The John Jay researchers have started examining the Municipal Archives collection of manumissions and legal records.

The Municipal Archives has already described and digitized the New Amsterdam records, including the original manuscripts and their English translations documenting proceedings, resolutions, minutes, accounts, petitions, and correspondence of the colonial government. When the Old Town records phase is completed, historians will be able to explore how colonial New York legal institutions and practices served as a foundation for the judicial system and guaranteed freedoms of the new Republic and answer important questions about a formative time period in the nation’s history.

Future blog posts will describe project progress and highlight unique “finds” in this rare collection.