The ferries are back. New York City is an archipelago of islands and ferries would seem to be an ideal mode of transportation, especially in areas not well-served by mass transit. And, for a while, through the 1920s, the City hosted an extensive network of ferries. Famously, Robert Moses initiated the destruction of the ferry system and subsequent decades saw decline and abandonment of most ferry lines. But now ferries once again ply the waters in an array of routes in and around New York City.

Cars and passengers aboard the Staten Island Municipal Ferry “President Roosevelt,” arriving in Staten Island, June 8, 1924. Department of Bridges, Plant & Structures photograph, NYC Municipal Archives.

In many regards the ferry history of rise, fall and rise again is typical of New York City’s infrastructure and transportation. According to Brian J. Cudahy author of Over and Back: The History of Ferryboats in New York Harbor, the trajectory of the municipal ferry system goes something like this. In 1905, the City of New York began a “progressive takeover of the ferry system” when it acquired the ferry route running between Whitehall Street (Manhattan) and Saint George (Staten Island) from the Staten Island Rapid Transit. By 1925, the New York City municipal ferry system had reached its pinnacle as it operated over a dozen routes that provided ferry service to all five boroughs and New Jersey. Twenty years later, only one municipally-operated ferry route remained, the same route that it started with in 1905, what today we call the Staten Island Ferry.

Municipal ferryboat “Bronx” traveling from Saint George (Staten Island) arriving at Whitehall Manhattan), circa 1905. Department of Docks and Ferries photographs, NYC Municipal Archives.

The Department of Docks and Ferries operated the New York City Municipal Ferry system between 1898 and 1918. Its successor agencies, the Department of Docks (1919-1942) and the Department of Marine and Aviation (1942-1977) operated the system. Today’s direct descendant agencies are the New York City Department of Transportation and the Economic Development Corporation which sponsors NYC Ferry service.

Department of Marine and Aviation staff at the office located at Pier A in Manhattan, circa 1955. Department of Marine and Aviation photographs. NYC Municipal Archives.

Our past, present, and future are tied to the waterways that surround New York City. Ferries have been an integral part of transport in the City for a very long time. The Staten Island Ferry route originally ran by the Staten Island Rapid Transit and taken over the City has been in service since 1816. In 1904, the year before the municipal ferry system was established, there were 147 ferryboats in operation on the waters around New York City.

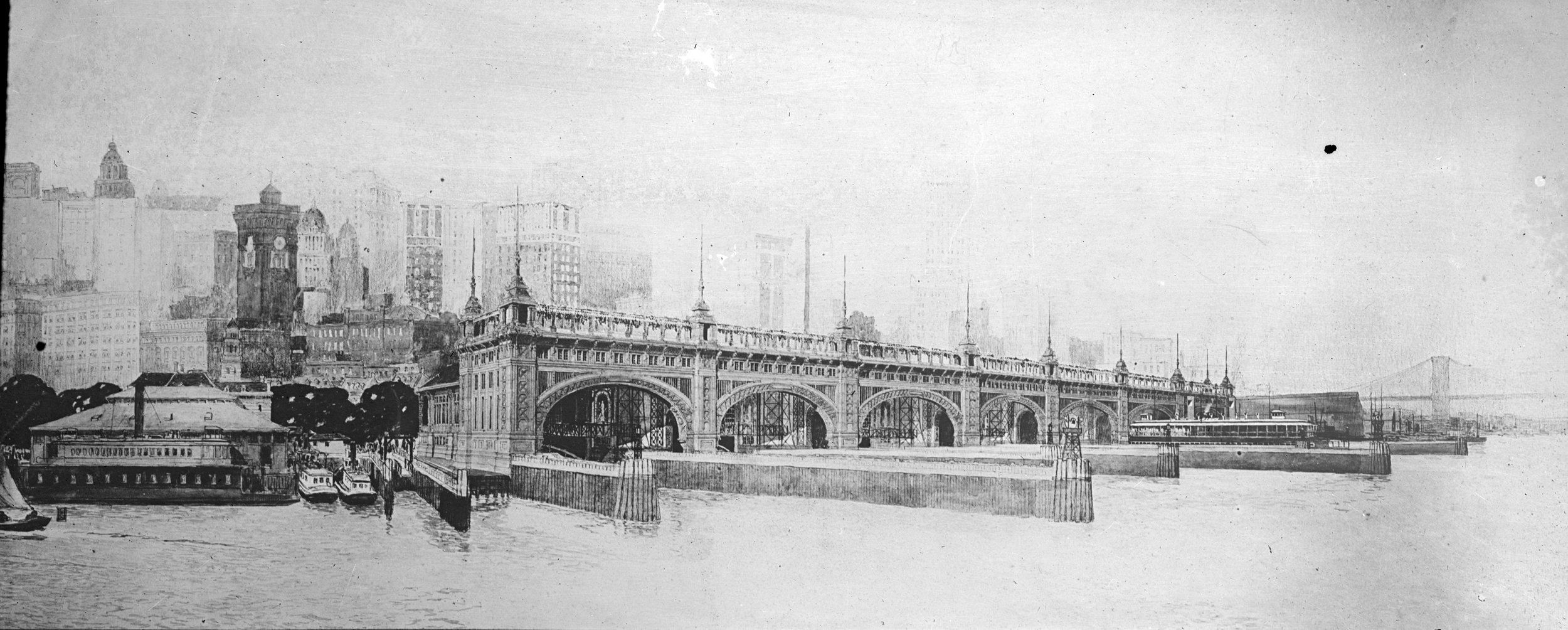

Perspective drawing of the Municipal Ferry Terminal, undated. In the original design, the terminal had two buildings, one with two slips going between Whitehall-Saint George (opened in 1906), and the other for the 39th Street Ferry that went to South Brooklyn (opened in 1909). It is now called the Battery Maritime Building and was listed on National Register of Historic Places in 1976.

Construction of the 39th Street Ferry House, 1908. The second ferry route to be acquired by the City was the Whitehall Street-39th Street (Brooklyn) route that it took over from The New York and South Brooklyn Ferry and Transportation Company in 1906. Department of Dock and Ferries photographs. NYC Municipal Archives.

Municipal ferry service initially was established during the administration of Mayor George B. McClellan (in office from 1904-1909) but it really grew during the Hylan Administration (1918-1925) as new ferry routes were established and ferryboats were designed and purchased by the City.

Even though municipal ferry service in the City underwent a period of growth from 1918 to 1925, it’s decline began shortly after reaching its pinnacle in the mid-1920s. There were two contributing factors—the Stock Market Crash of 1929 that led to the Great Depression; and the construction of tunnels, bridges, and roads for the almighty automobile. The near decade-long economic depression that began in 1929 meant that the City had less revenue and therefore less money to spend. Funding for the municipal ferry system in New York City was one of the numerous municipal services that were cut. That said, during this same economic depression, public money was used for the construction of automobile infrastructure. Not coincidentally, this infrastructure for automobiles crossed over or tunneled under New York City-area waterways replicating many of the ferry routes.

This pattern of replacing mass transit ferry routes with bridges and tunnels primarily designed for single, privately-owned car commuting would continue into the 1960s, thus contributing to the demise of the municipal ferry system and the rise of the gridlocked highways we are left with today. For example, the City’s Astoria Ferry that ran between East 92nd Street (Manhattan) and Astoria (Queens) operated from 1920-1936 when it was discontinued after the opening of the Triborough Bridge in 1936; the City discontinued the Clason Point (Bronx) to College Point (Queens) route that operated from 1921-1939 after the construction of the Bronx-Whitestone Bridge in 1939; and the municipally-operated Rockaway Ferry that ran from Flatbush Avenue in Brooklyn to Jacob Riis Park in the Rockaways was in operation from 1925-1937 when it was discontinued following the opening of the Marine Park Bridge.

Clason Point Ferry House in disrepair, 1951. This Municipal Ferry route was in operation from 1921-1939. It ran between Clason Point in the Bronx and College Point in Queens. Department of Marine and Aviation photographs. NYC Municipal Archives.

Although it is sometimes hard to remember when you’re deep underground on the subway or hustling between skyscrapers in Midtown, New York is a maritime city. It has approximately 520 miles of coastline, more than Los Angeles, San Francisco, Miami, and Boston combined. Thirty-nine of the New York City Community Boards have some access to the waterfront. It should not be surprising then that these very waterways have been used for transit for thousands of years. What is surprising, however, is how quickly these natural “roads” fell from favor as a means for transporting people, especially in comparison to cars and other surface transit.

In recent years, the City has reconsidered how it moves people around equitably, and how to deal with the transit deserts in many neighborhoods. And as so many communities are located near waterways, the ferry is once again becoming an integral part of the public transit network. Not to mention that riding the ferry is fun, relaxing, and a great way to experience the amazing city.

View from the Soundview route of the NYC Ferry heading from Pier 11 in Lower Manhattan to Soundview in the Bronx, 2019. Photo by Patricia Glowinski.

The New York City Municipal Archives and Municipal Library hold many primary and secondary sources documenting the New York City Municipal Ferry system and the City agencies that administered it. These include the Department of Docks and Ferries and Department of Docks annual reports and minutes, 1888-1939 (though with gaps of some years); report on the operation of municipal ferries by the City of New York from 1905 to 1915; Department of Ports and Trade pier removal contract files, 1956-1966; Regulations for the governance of municipal ferry employees, 1910; Department of Docks and Ferries photographs; and Over and back: the history of ferryboats in New York Harbor by Brian Cudahy. Archival material documenting the administration of the New York City Municipal Ferry can also found in numerous mayoral records including the records of Mayor George B. McClellan Jr., 1903-1909; Mayor William J. Gaynor, 1909-1913; Mayor Ardolph L. Kline, 1913; Mayor John P. Mitchel, 1869-1917 (bulk 1914-1917); Mayor John F. Hylan, 1912-1925; and the Mayor Fiorello H. La Guardia, 1864-1954 (bulk 1934-1945).

Commuters on the ferry from Hoboken, N.J., to Barclay Street, circa. 1937. WPA Federal Writers’ Project photograph, NYC Municipal Archives.