The Municipal Archives recently completed digitizing the 1890 Police Census. Supported by a generous grant from the Peck-Stackpoole Foundation, project staff reformatted all 894 extant volumes of the collection to provide access (113 volumes are missing from the collection). They re-housed the volumes in custom-made archival containers to ensure their long-term preservation. Long prized by family historians, the census provides unique documentation of approximately 1.5 million inhabitants of New York City. To further enhance access to the valuable information in this series, the Municipal Archives has invited anyone with an interest to participate in a transcription project.

42nd Street, looking east to 6th Avenue Elevated, ca. 1890. DeGregario Family Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

Provenance of the Census

“It is the right of the people of New York to be counted accurately and to have representation in Congress and in the Electoral College proportionate to their population. In their name, I demand as their right, that the federal authorities make an accurate enumeration of all the inhabitants of the City of New York.” Mayor Hugh Grant, October 16, 1890.

As it had done every ten years since 1790, federal census takers conducted an enumeration of the City in 1890. The count took place between May and June. New York City Mayor Hugh Grant and other city officials believed the federal census significantly undercounted inhabitants. To support their claim, Grant ordered the Police Department to conduct another census. It took place between September 29, and October 14, 1890. The new count showed a gain of 200,000 people in the population, compared to the federal number.

“Not Allowed”

Based on the results of his “police” census, Mayor Grant submitted a letter to the Superintendent of the Census in the Department of the Interior requesting a re-count. The Federal office refused. Grant submitted a second request; also denied. The Municipal Archives mayoral records from the Hugh Grant administration includes the lengthy correspondence from the Department of the Interior detailing their reasons for not conducting another census of the City. In his cover letter to Mayor Grant dated October 27, 1890, Interior Secretary John W. Noble concluded, “There is sent you herewith an opinion answering your demand for a renumeration of the inhabitants of your city, which, for reasons therein set forth, is not allowed.” Noble attached a fifteen-page document listing the reasons for declining to conduct another census.

Noble’s analysis included the statement that part of the difference can be attributed to the “...matter of common observation that many thousands of people of the City of New York give up their abodes in June of each year for vacation or recreation abroad or in the surrounding country, and many thousands more go to service with them...” Noble also observed “There is also a natural increase of population in one fourth of a year.” At that time, the arrival of new immigrants, many thousands per month, could account for the greater population recorded by the City in October, compared to the federal count in June. Mayor Grant’s second request resulted in another denial with a similar eight-page attachment.

Lower East Side street, ca. 1890. Department of Sanitation Photograph Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

It is important for researchers to note that Mayor Grant’s outgoing correspondence in this matter will be found in the “letterpress” volumes. Maintained as a separate series, outgoing correspondence from mayoral offices during the latter part of the nineteenth century is in the form of carbon copies on thin onion-skin paper bound into volumes. There are approximately 160 volumes in the series; each volume is generally indexed by the name of the correspondent, or subject. Collection Guides provides further information and an inventory of the series.

The whereabouts of Mayor Grant’s “police” census within New York City government offices after 1890 is not known. Likewise, there is no documentation of when the Municipal Archives received the census volumes, but it has been part of the collection since at least the early 1970s. There is also no information about the 113 missing volumes.

The fate of the federal 1890 census is known, however. In 1921, a fire in the basement of the Commerce Building in Washington, D.C. damaged hundreds of thousands of pages. Although the charred pages were salvaged, in December 1932, the Chief Clerk of the Bureau of the Census submitted a record disposal application to the Librarian of Congress that included what remained of the 1890 census record. On February 21, 1933, Congress authorized destruction. [1]

High view looking north from 23rd Street up Broadway, ca. 1890. William T. Colbron, photographer. DeGregario Family Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

The Digitization Project

In 2022, the Peck Stackpoole Foundation awarded the Municipal Archives a grant to determine the feasibility of digitizing the census collection. Based on productivity achieved during the pilot, the Foundation awarded a second grant in 2024 to complete digitization.

The Municipal Archives employed a digitization technician, Marie Cyprien, to complete the task. In accordance with Federal Agencies Digital Guidelines Initiative (FADGI) recommendations, Ms. Cyprien captured the images using an overhead camera. She converted the raw images to other formats via batch processing. She created preservation format TIFF files and applied file-naming standards according to Municipal Archives standards.

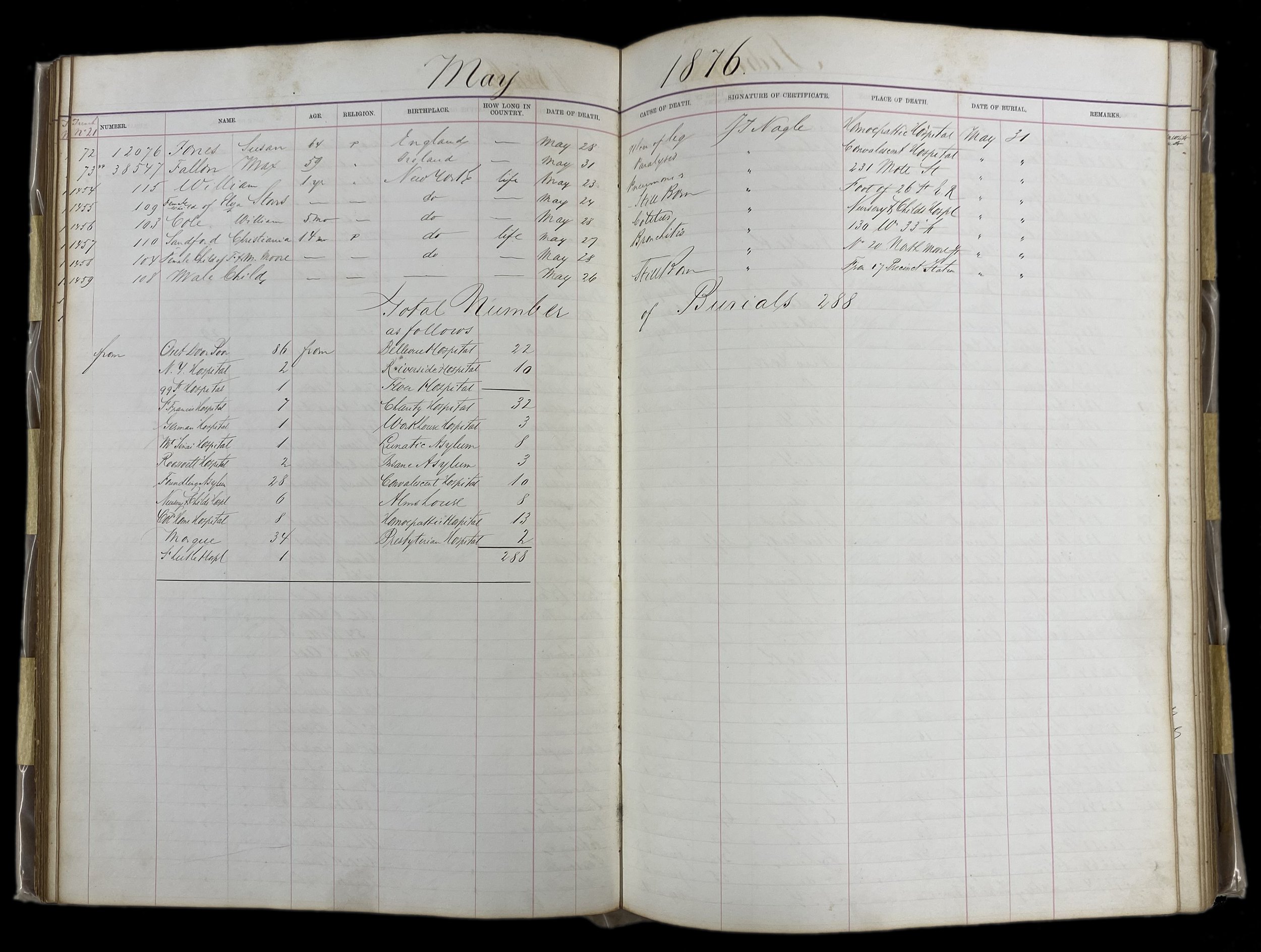

Completed in December 2024, digitization of the 894 ledgers in the 1890 New York City Police Census collection resulted in 77,844 images. Ms. Cyprien also completed the necessary collection rehousing into 39 custom boxes, barcoding, and labeling the volumes.

The 1890 Police Census

239 East 114th Street, home of the “Marks” family, with children “Leo and Adolph,” better known as Chico and Harpo, of the Marx Brothers. Julius, aka “Groucho” Marx, was just missed in the census as he was born at this address on October 2, 1890. 1890 census, NYC Municipal Archives.

The 1890 New York City Police Census produced 1008 volumes; 894 volumes are still extant. Each volume lists the population of one election district in New York County. A map of the election district boundary can be found on the last page of each volume. Prior to the consolidation of New York City in 1898, the boundary of New York County was contiguous with the island of Manhattan, plus annexed districts of what is now the Bronx. The 1890 census includes the western portion of the Bronx that was annexed in 1874, but not the eastern portion annexed in 1895. As Brooklyn, Queens, and Staten Island would not be boroughs of the city until 1898, they are not included in the census.

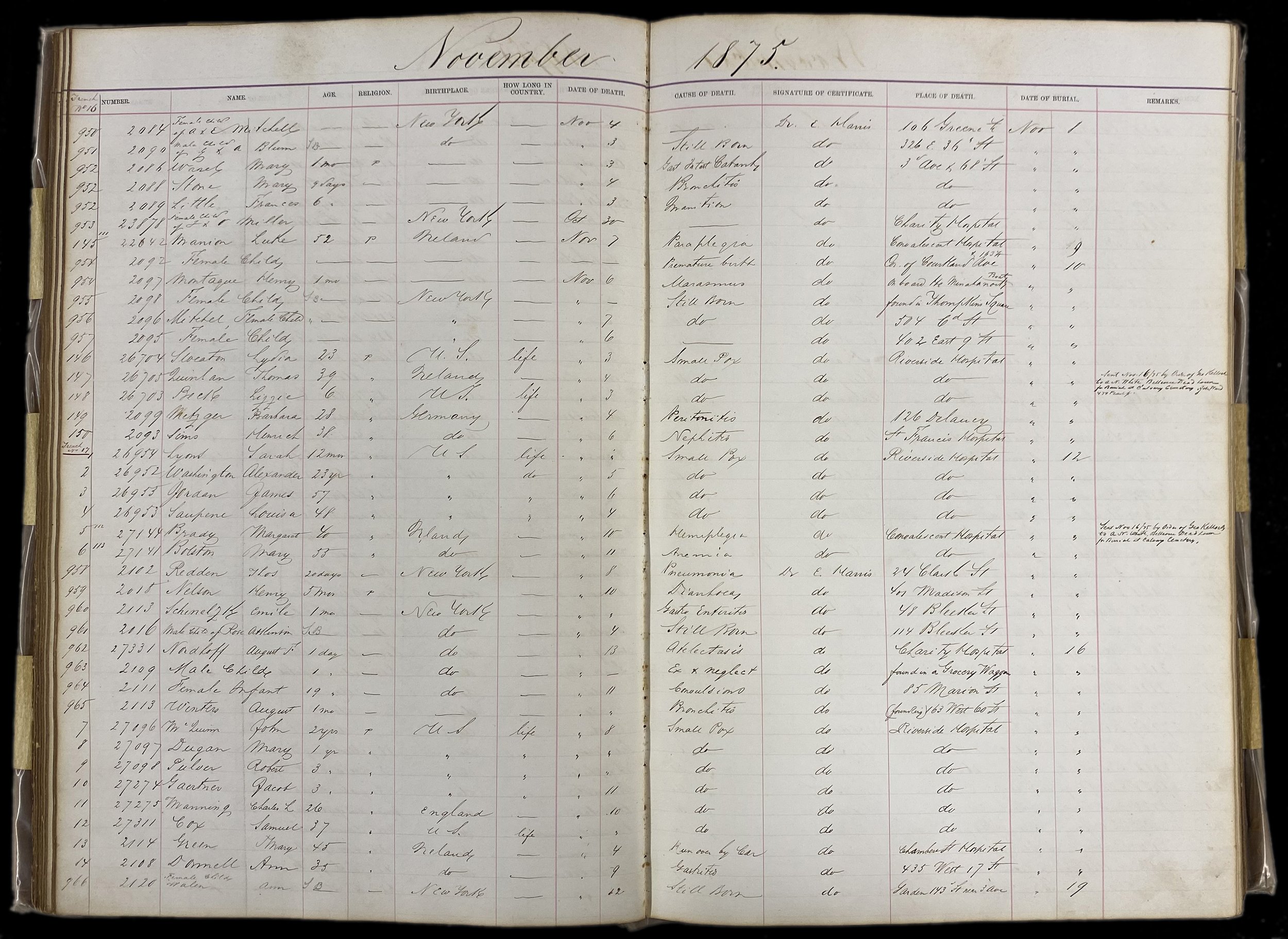

New York City police officers conducted the census. The handwritten entries record election district, assembly district, police precinct, name of the police officer/enumerator, and the address, name, gender, and age of each resident. There is no indication of the relationship of one person to another, occupations, or other demographic information.

Significance of the collection

Loss of the federal 1890 census makes the City’s version uniquely valuable in bridging the gap in demographic information between 1880 and 1900. Immigration to the United States surged during that period; in 1890, newcomers comprised 42 percent of New York City’s total population. The census is particularly useful in documenting children. Due to language barriers and differing cultural traditions, many families failed to report the births of their children to the City’s Health Department. The 1890 police census can be used to identify the names and approximate date of birth for the estimated 15-20 percent of children without civil birth records.

Next Steps

The Municipal Archives Collection Guides describes the census record and provides a link to the digital images. Interested persons are invited to visit From The Page for information about the recently launched project to transcribe and index the1890 census. Look for future For the Record articles that will describe how to use this essential research resource.