George William Stillwell enlisted in the Union Army on April 27, 1861. He fought in Civil War battles at Yorktown, Williamsburgh, Fair Oaks, and White Oak Swamp. Achieving the rank of Captain, he commanded a Regiment at the 2nd Bull Run, Fredericksburgh, under General Ambrose Burnside. He resigned his commission on account of physical disability.

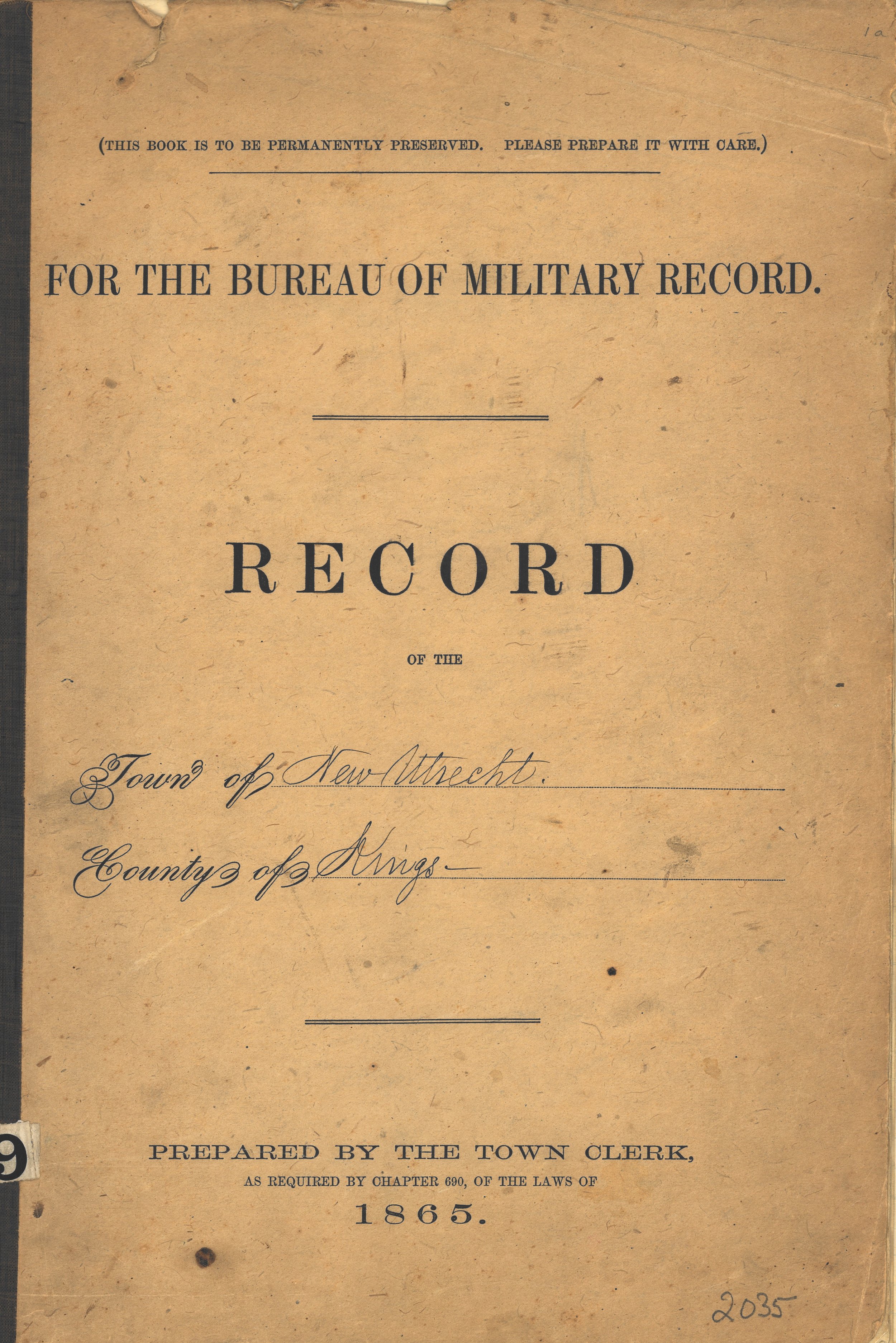

Town of New Utrecht Record for the Bureau of Military Record, Old Town Records collection. NYC Municipal Archives.

Captain Stillwell’s son James Henry Stillwell also enlisted in the Army about a month after his father. He fought in battle at Fair Oaks where he was mortally wounded. He died on June 30, 1862, at age 18. These entries appear in the Record of Troops: Roll of Persons Liable to Military and Quota of Troops Furnished in the War of Rebellion for the Town of New Utrecht, 1851-1865.

This ledger-format record, and three similar items from the Kings County Towns of Flatbush and Flatlands are part of the Old Town Records collection. Recently processed and partially digitized with funding from the National Historical Publications and Records Commission, this large collection (1,272 cubic feet), consists of records created and/or maintained by towns and villages in Kings, Queens, Richmond and Westchester Counties before they were dissolved, annexed, or consolidated into what is now the City of New York. They document administrative, court, financial, land, voting, and tax transactions. The collection includes records of military service as well as information documenting enslaved people.

Although few in number, these Civil War-era ledgers are of particular value due to the unique information about the men recorded in the ledgers. Not only do they provide a summary of the soldier or seaman’s military service, they also indicate demographic data, e.g. places of birth, parents’ names and occupations.

Captain Stillwell was born on February 9, 1813, in New Utrecht. His parents were Thomas Stillwell and Catharine Bennett. His son, James Henry, was born on September 10, 1844, in Brooklyn. His parents were George W. Stillwell and Margaret Bird. Birthdates of both father and son pre-date official birth record-keeping and these ledger entries may provide the only evidence of their birth. Examining the nativity of the other soldiers and sailors listed in the ledger confirm that both native-born men and new immigrants served in the Civil War.

Town of New Utrecht Record for the Bureau of Military Record, Old Town Records collection. NYC Municipal Archives.

Town of New Utrecht Record for the Bureau of Military Record, Old Town Records collection. NYC Municipal Archives.

The Civil War-related records were created pursuant to a New York State law, Chapter 690 of 1865: “An Act in relation to the bureau of Military Statistics.” The legislation was enacted “To collect and furnish to the bureau of military record, and to preserve in permanent form for the county, a record of the miliary services of those who have volunteered or been mustered, or who may hereafter volunteer or be mustered into the service of the general government from the county since the fifteenth day of April, eighteen hundred and sixty-one, and a brief civil history of such person, so far as the same can be ascertained.” The full text of the law is available in the Municipal Library.

Civil War Veterans, Flushing, Queens, lantern slide, n.d. Borough President Queens Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

The Stillwells were not the only New Utrecht family to suffer grievous loss in the Civil War. Researchers reviewing the ledger entries will be struck by the number of men recorded as dead or wounded. On the same page listing the Stillwells there are four other men, William Ackley, James Cozine, William Haviland and Leffert Benson, who are recorded as deceased. According to the ledger entries, William Ackley, a farmer, remained with his regiment until Chapins Farm when he was “instantly killed on the battle field and there buried.” James Cozine was “wounded in the seven days before Richmond . . . since dead and buried in Gravesend.” William Haviland had been in the battle of Williamsburgh and “afterward taken sick returned home and died April 9, 1864.” Leffert Benson had “taken sick and died at Fortress Monroe, buried at New Utrecht, April 2, 1863.”

The transcribed version of the New Utrecht ledger has been digitized and is available via the Department’s website.

These records demonstrate the profound effect the Civil War had on communities throughout the City. For the Record recently reviewed The New York City Civil War Draft Riot Claims Collection. Look for future posts that examine other records that document this significant era in New York City and United States history.