The Sunshine Movie Theater on Houston Street, which was being used as a warehouse in the mid-1980s. Note the graffiti: “Stop Gentrification.” If they only knew. DOF Tax Photograph Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

The recent digitization of the Municipal Archives collection of 1940s tax photographs, and the subsequent interest by the New York Times in the 1980s Tax Photographs, got us thinking about the truly weird history of the 1980s Tax Photographs.

Let’s start with the 1940s pictures. The Department of Taxation (as the City’s Department of Finance was then called) had started the photograph project in 1939 with help from the Works Progress Administration (WPA). Only part of Manhattan was shot in late 1939; most of the rest of the city was shot in 1940 and in early 1941. Work continued on the project until 1943, at which point WPA support ended, and the Department of Taxation took full control of the project. During the post-war boom, from 1946 to 1951, Taxation shot over 50,000 new photographs. The Municipal Archives has most of those negatives, but after 1951 the only records of the reshoots are the prints attached to the property assessment cards. These are dutifully stamped with the year, 1966, 1971, and so on. In some instances in the late 1970s color Polaroids of the property were attached.

3247 Richmond Avenue, Staten Island, ca. 1983. DOF Tax Photograph Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

A 12-inch Laser Video Disk containing photographs of Manhattan from the 1980s Tax Photo project.

This all worked out well for a time, but by 1979 the city had changed dramatically since 1939. The renamed Department of Finance realized that the time had come to completely redo the tax photographs. This updating of the 1940 photos took place from late 1982 to 1987 with some reshoots done in 1988. Using color 35mm film, the photographers captured every lot in the five Boroughs, including vacant property. And frustratingly, if the building was a condominium, they took as many identical photographs as there were apartments (each apartment in a condominium is assigned an individual lot number). Staten Island was the first borough photographed, because it had been transformed after the construction of the Verrazano Narrows Bridge in 1964. However, it was undergoing such rapid development in the 1980s that there were even more changes by 1987. Consequently much of Staten Island had to be reshot at the end of the project.

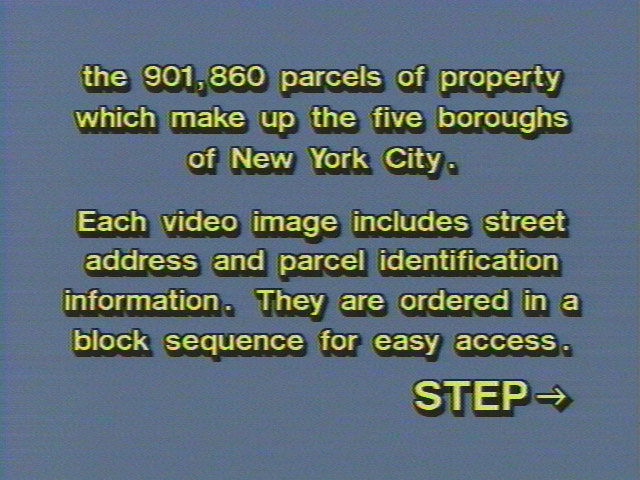

One of the questions we most often get about the 1980s Tax Photos is why do they look so murky online? Here is the answer. In order to provide the public with a state-of-the-art user experience, the Department of Finance made 4x6 mini-lab prints of the photographs, recorded them frame-by frame using a video camera, and transferred the frames to Laser Video Disks (LVD). The Laser Video Disk was introduced in 1978 as the first commercially available optical media. The 12-inch-wide platters look like CDs on steroids, but only held 30 to 60 minutes of video. Not only that, but the signal encoded on them is analog not digital—at what we would consider today to be low-resolution.

672 8th Avenue, Times Square, as it appears captured from the LVD screen. DOF Tax Photograph Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

672 8th Avenue, Times Square, as it appears scanned from the negative. DOF Tax Photograph Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

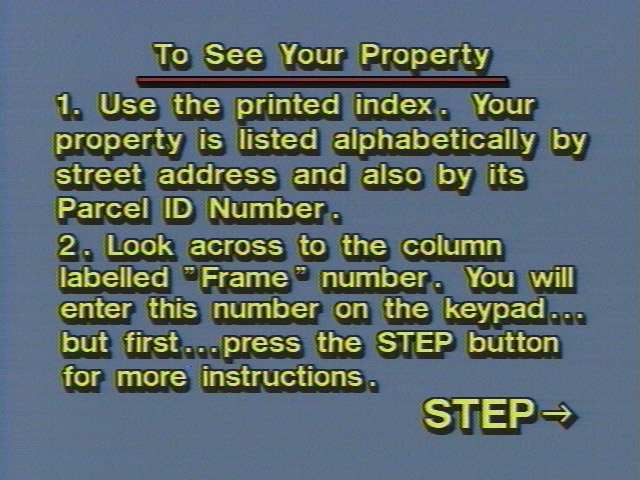

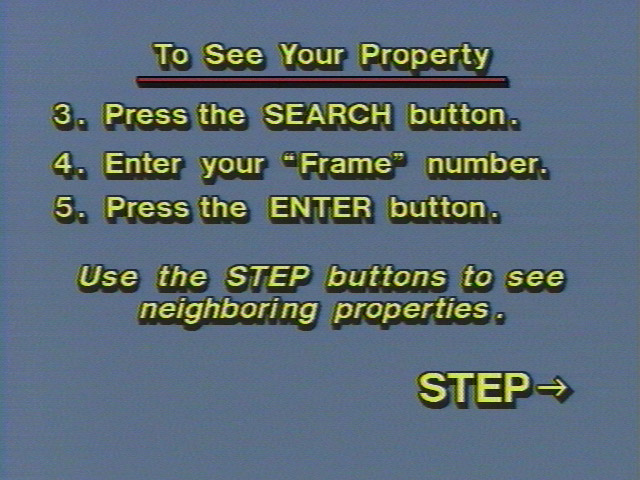

The system was not unique, and in fact multiple companies were selling similar technology in the mid-1980s to governments around the country and to real estate agencies interested in a system that could quickly pull up photographs of any property. Harvard even sponsored a conference on computer-assisted valuations. One of the few advantages of the LVD system is that it can skip to a direct frame input. When connected to a computer database it provided a searchable image bank. The NYC Department of Finance was interested in this system as part of their larger initiative of Computer-Assisted Mass Appraisal (CAMA). The director of both the CAMA initiative and the photographing project was James Rheingrover. The company that produced the LVD system was Landisc Systems of Dayton, Ohio (Cole, Layer, Trumble). Landisc had installed similar systems for other jurisdictions, but New York, with 900,000 photographs was the largest.

In 2009, Jim Rheingrover provided me with a lot of the project’s background. At its peak, they had 60 people in the field, working in teams of two, as photographers and data-collectors. The first photographers were originally data-collectors and then a photo component was added to the project. They tried not to hire photographers because photographers wanted to take “good” photographs and Finance wanted fast photographs. Many of the original data-collectors were highly-educated though, with a few PhDs in the bunch. They were not well paid, he recalled, but it was a recession. The photographers had to go through some tough neighborhoods in the 80s. He pointed out that there generally aren’t any people in these photographs because the photographers tried to wait until no one was in frame to avoid incidents. Often people were suspicious that the teams were undercover cops so the photographers always “wore their dorky DOF badges prominently displayed.”

Department of Finance staff demonstrating the laser video disc system to Mayor Edward Koch during a press conference, December 15, 1988. The image on the screen is City Hall. Mayor Edward I Koch Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

311 Roebling Street, South Williamsburg, ca. 1985. DOF Tax Photograph Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

He recalled only a couple of thefts (although the Times reported in 1987 that there were none), one camera stolen during a mugging and another one “supposedly” stolen from the trunk of the photographer’s car. The photographers were responsible for their own cameras and if any went missing the replacement cost came out of everyone’s salary. One of the staff developed the metal arm that attached to each camera so that the block and lot number would be in focus with the aperture stopped down. They never used tripods for the cameras. The film was 400 ASA Kodak film bought in bulk from Focus Electronics in Borough Park, Brooklyn.

The “Sanborn Team” would sit with a Sanborn map and the photograph and fill out a form for every property. He said condos have always caused a problem with data-collection and they probably should have kept the original lot number and assigned them a sub-number. The decision to take a photograph for every condo apartment was ultimately Jim’s since everyone reported to him. He said in retrospect it was a stupid idea, but it was done because they needed an image to attach to their data-collection forms.

In 2006 the Municipal Archives retrieved the 1980s tax photographs from the basement of the Municipal Building. They had been languishing in file cabinets in a cramped storeroom near the boiler and the abandoned northern entrance to the JMZ line. The archivists discovered that no one had the keys to the file cabinets and were forced to drill out the locks and pry them open. Grants from the New York State Library supported processing of the massive collection of negatives and 4x6 prints, and supplies—e.g. 250,000 negative sleeves.

528 E. 148th Street, South Bronx, ca. 1985. DOF Tax Photograph Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

But how would people access the collection? In 2009 we turned to the LVD system. Could we download the files from it? No. It was an analog system. Hmm, could we do screen captures? Yes, but how would we capture and name some 850,000 frames? A former intern who had become a software programmer discovered that code to operate a computer-controlled LVD player was readily available online. The same technology was the basis of the classic arcade game Dragon’s Lair, which was a sort of Choose Your Own Adventure animation more than a video game, but relied on an internal LVD player for content.

The system we rigged up played one frame of the LVD, paused it, and then saved a screen capture. Repeat. The whole process took over 8 hours for a single side of a disk and there were 21 sides to complete. For months I would start a disk in the morning, and if I worked a long day I could start another one in the evening. Sometimes we found that the player stuck and one frame might be saved multiple times and that session had to be scrapped. The original player acquired from the Department of Finance had a defective computer interface card, but the one we found on e-Bay had a faulty pause mechanism. So I took the interface card from it and put it in the original machine. Voila, a functioning player!

The LVD player during screen capture of the 1980s Tax Photos at the Municipal Archives.

This highlights one of the problems with any sophisticated technology… external dependencies. The Times had gushingly reported in 1987 that the LVDs would last 300 years and provide what the chairman of the Landmarks Preservation Commission called “an archive of this civilization.” But just over two decades later we were struggling to find a working LVD player. The next challenge was finding the corresponding data that would identify these screen captures. After several failed attempts, the Department of Finance was able to find a back-up tape of their RPAD (Real Property Assessment Data) from 1990. It required several months to edit the coded database into something a human could read and link it to the LVD frames. From start to finish the whole project took about a year.

We recognize that the final chapter of the tax photo project is to go back and digitize the original negatives, but without those weird clunky LVDs there was no way users could preview the properties, which they’ve done now for ten years.

2803 Third Avenue, South Bronx, ca. 1985. Fashion Moda was an important artist space in the birth of Hip Hop and Graffiti culture. DOF Tax Photograph Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.