The New York City Municipal Library collects and makes available information about government operations. One series in the Library’s collection is the idiosyncratic vertical files. Named thusly because the folders of miscellaneous clippings, news releases, promotions, etc. are stored in vertical file cabinets. An eye-catching subset of these files consists of six folders of information about receptions in New York City.

The first folder, titled NYC Receptions (General), is followed by five others that are organized alphabetically. Oddly, the first items in the General Reception folder are misfiled biographical information about the City’s once peerless greeter, Grover Whalen, that belong in the Biographies notebooks. For 35 years, Whalen welcomed dignitaries as head of the Mayor’s Committee on the Reception of Distinguished Guests during seven mayoral administrations, beginning with Mayor John Hylan, and concluding with Mayor Vincent Impellitteri. Whalen is credited for inventing the ticker tape parade in 1919 when the Prince of Wales was showered with paper from stock tickers.

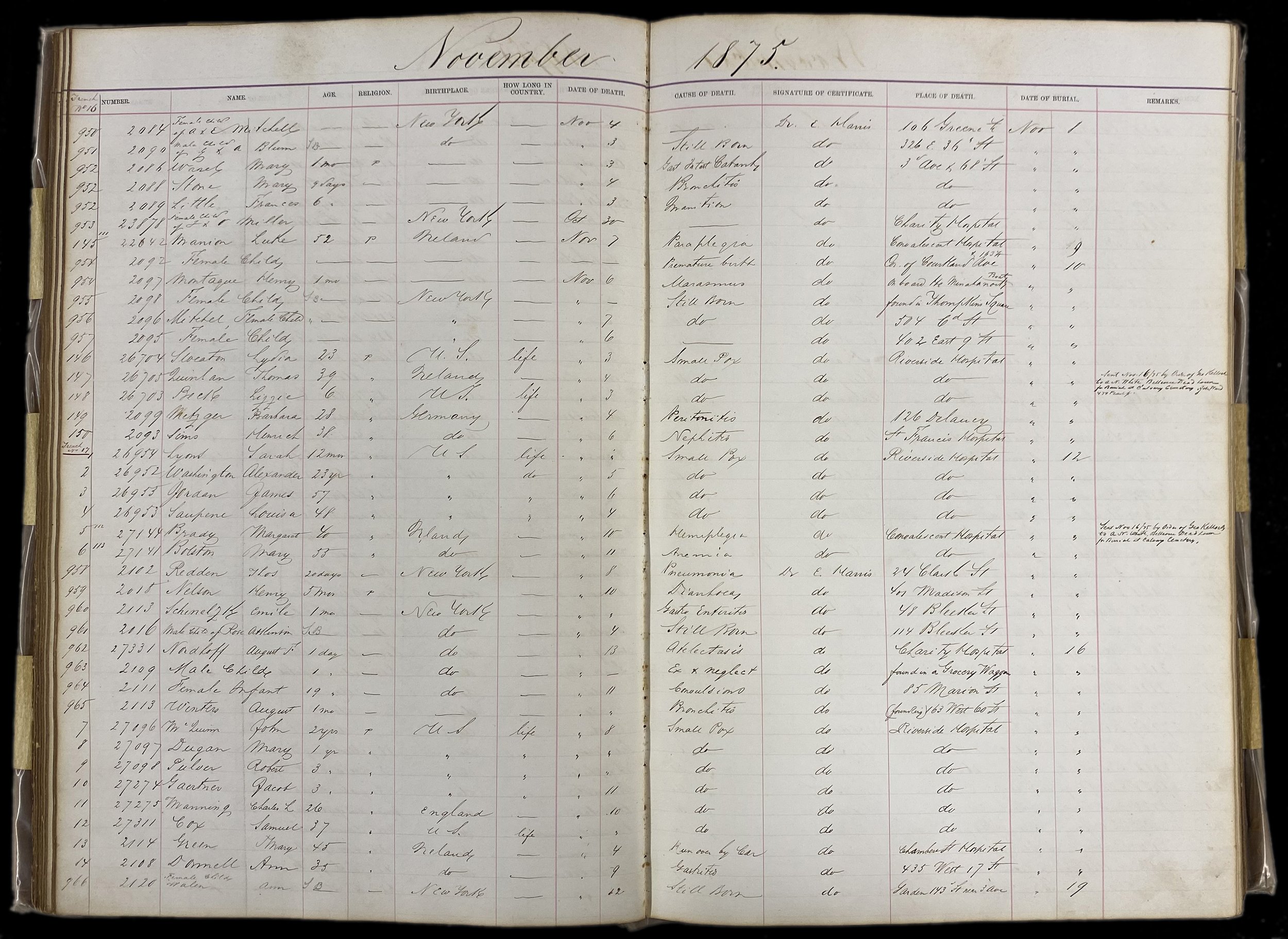

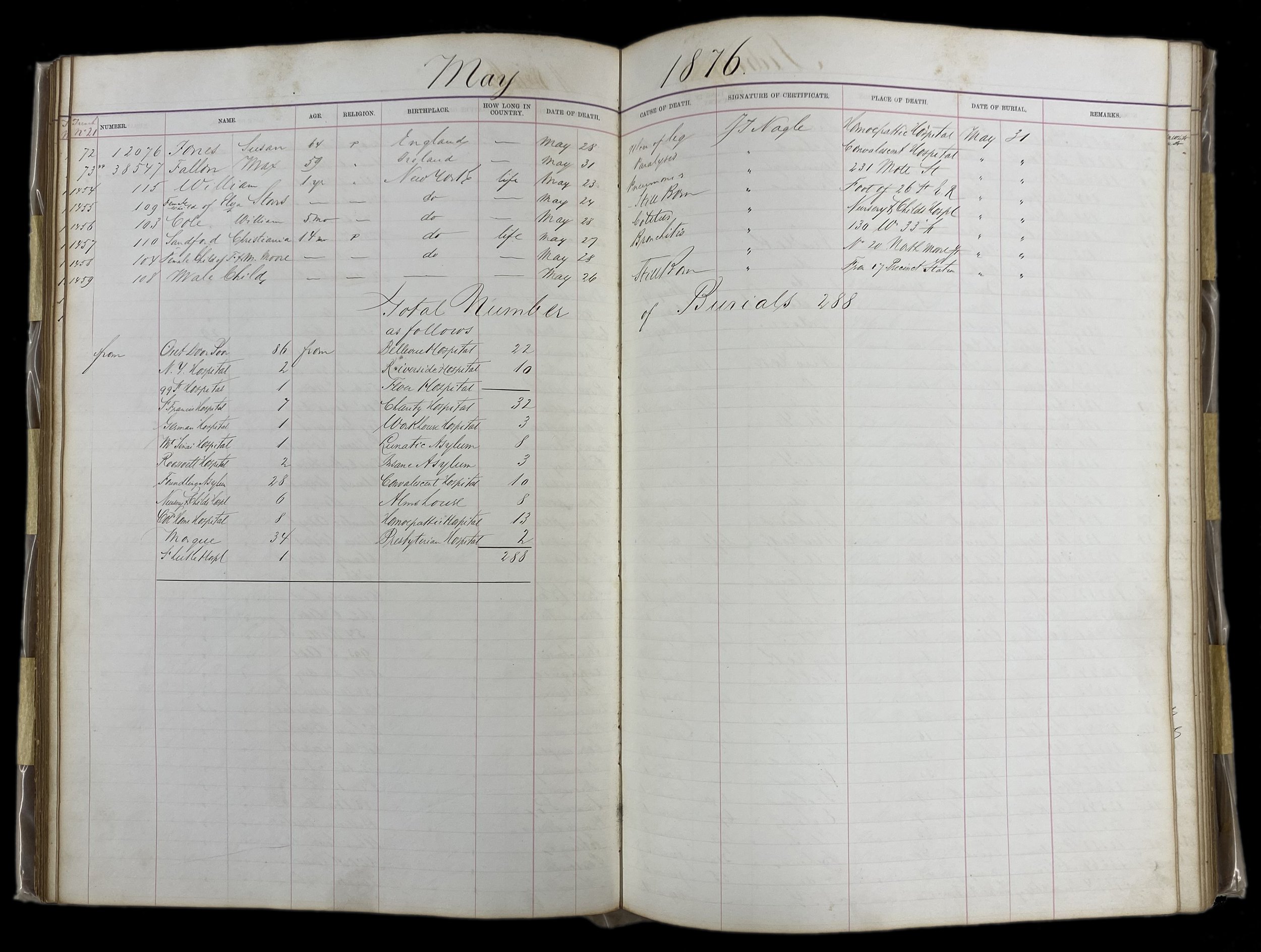

The folders contain itineraries, pronunciation information issued by the Office of the Chief of Protocol at the Department of State, membership lists of the official parties, menus, background notes from the State Department, Police Department assignments and of course, newspaper clippings. They document parades—both with and without ticker tape—presentations of citations, bestowing of medals, receptions and dinners.

According to a New York Herald Tribune article from 1950, the first parade from the Battery to City Hall to honor an individual was for the Marquis de Lafayette on August 16, 1824. The article, an imagined account from the Marquis’s visit, called the parade “the most triumphant welcome ever given a guest of this city.”

The files memorialize a large number of parades honoring the members of the armed services. In fact, the first parade that Whalen organized was for servicemen returning from World War One in 1918.

General Dwight Eisenhower stands to wave to spectators along the parade route. Mayor LaGuardia is seated. June 19, 1945. Municipal Archives Photograph Collection. NYC Municipal Archives.

General Dwight D. Eisenhower did not just trek to City Hall from the Battery. He traversed 37 miles of streets lined with New Yorkers shouting their approval.

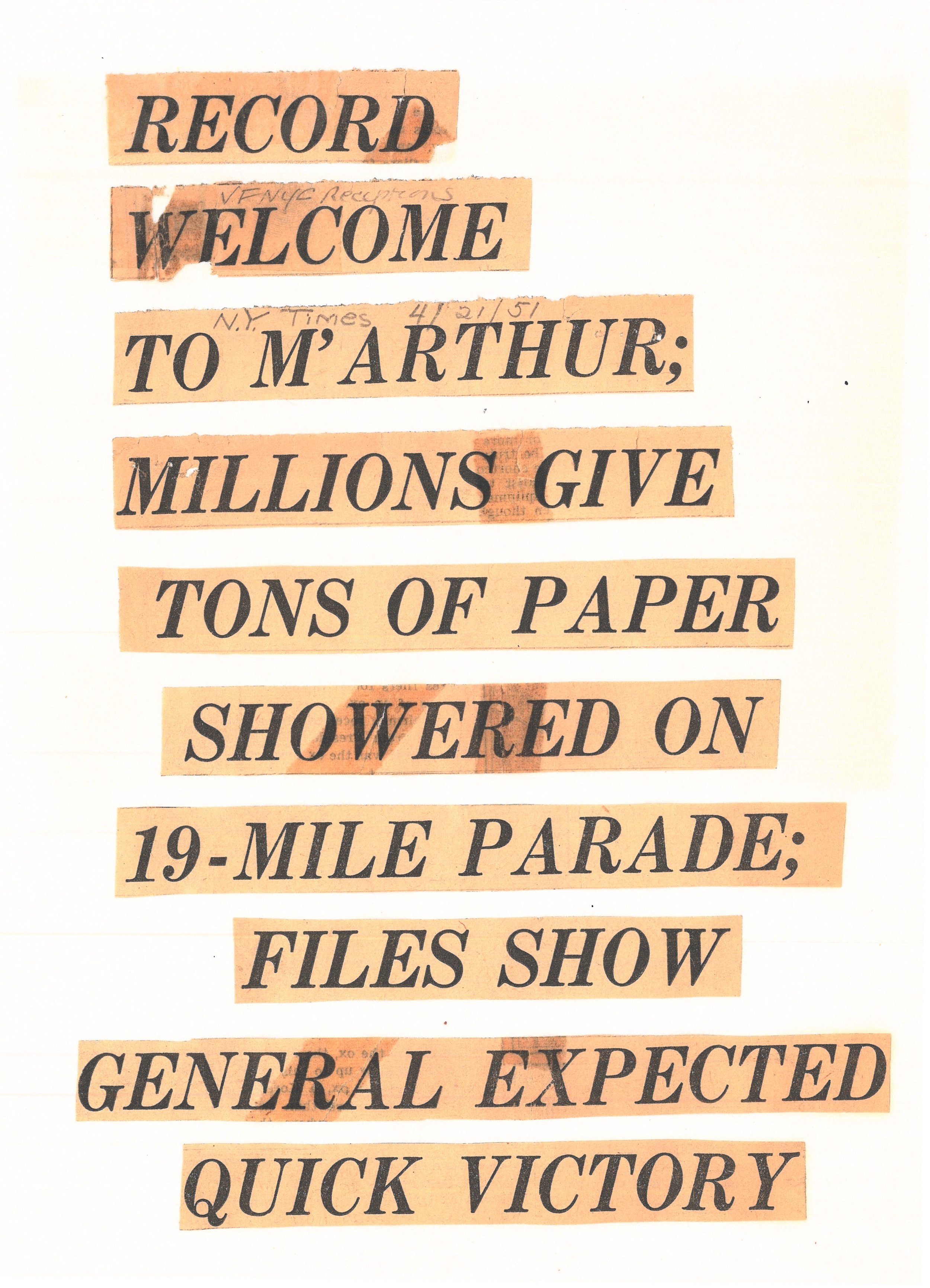

Article headline clipped from New York Times, April 21, 1951, describing parade for Gen. Douglas MacArthur. Municipal Library Vertical Files. NYC Municipal Library.

The City’s Police Commissioner estimated that 7.5 million people lined city streets to cheer for General Douglas MacArthur on April 20, 1951, and the Sanitation Department reported spectators dropped 2,850 tons of paper during the parade. If the crowd estimates were true, the New York Times calculated that “would leave only 335,099 New Yorkers at home or at work.” The parade route deviated from the regular Battery to City Hall and instead started at the Waldorf Astoria at 49th and Park Avenue, wound its way through Central Park, across 102 Street, eventually meandering through nineteen miles of City streets until reaching City Hall where the General received a gold medal and then returned to the hotel. “Half an hour after the general returned to the Waldorf the city had resumed its normal weekday aspect,“ according to the Times.

Mayor’s Reception Committee Program for Reception to Major General William F. Dean, October 26, 1953. Municipal Library Vertical Files. NYC Municipal Library.

A quarter of a million New Yorkers greeted the thousand soldiers from the 45th Infantry Division who had just returned from Korea April 22, 1954. It was a surprisingly warm Spring day and “a hot spring sun caused several of the men to collapse” with heat prostration, according to the Herald Tribune. Again in 1957, Korean Veterans were honored and presented with the Medal of Honor of the City of New York by Mayor Impelitteri. The veterans in this instance hailed from nineteen different nations that made up the force fighting under the United Nations banner in the war. United Nations Undersecretary Dr. Ralph J. Bunche praised their service.

A somewhat unusual parade was held for a nurse who was stationed at Dien Bien Phu during the battle between the Viet Minh and the French in 1954. Taken prisoner by the Vietnamese army and then released, Genevieve de Galard-Terraube was invited to New York by the United States Congress, “the third foreigner ever invited here by Congress,” which had unanimously adopted a resolution. The Marquis de Lafayette and Hungarian revolutionary Louis Kossuth preceded her, according to the Herald Tribune.

The United States Conference of Mayors began a 1952 session with a parade up Broadway to City Hall where they were greeted by the Mayor. The officials later discussed traffic congestion, municipal finance, municipal bonds and the price of steel.

Even newspaper reporters were honored. In 1938, Mayor LaGuardia and the Board of Estimate welcomed two reporters—Dorothy Kilgallen from the New York Evening Journal and Leo Kieran from the New York Times, who had completed “a round-the-world trip made chiefly by airplane.” The Bronx Borough President invited them to enjoy the “salubrious air of the Bronx.”

Some things never change. In 1937 a group of English students who were learning about different cultures through direct experience met with Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia who told them they “would not know New York until they had ridden in the subway during rush hours.”

Program cover for event honoring Mercury Team astronauts, March 2, 1963. Municipal Library Vertical Files. NYC Municipal Library.

Astronauts also figure prominently in these files. America entered the space age in 1955 and New Yorkers were as eager to cheer them on as anyone else. John Glenn, the first American to orbit the Earth, received a hero’s welcome and ticker tape parade to celebrate the milestone in 1962. Former President Herbert Hoover and then Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson joined Mayor Robert Wagner in honoring Major Leroy Gordon “Gordo” Cooper and the other members of the Mercury team in 1963. The Mercury Team members were the first Americans to orbit the Earth and Cooper had the longest stint—22 orbits completed in just over 34 hours, which demonstrated that humans could survive on space trips.

Broadway was renamed “Apollo Way” when the astronauts from Apollo 8 marched up to City Hall in frigid weather January 10, 1969. Apollo 11 astronauts, Neil Armstrong, Michael Collins and Edwin “Buzz” Aldrin received heroes welcome on August, 13, 1969, after returning from their mission to the moon. Protestors disrupted the City Hall event for the Apollo 14 crew, chanting, “Crumbs for the children and millions for the moon” according to the New York Times. This led Captain Alan Shephard Jr. to urge people to compare the budget for space exploration with that spent for domestic matters, saying “you will be surprised at the ratio.”

Program cover for dinner honoring United States Olympic Team, October 2, 1920. Municipal Library Vertical Files. NYC Municipal Library.

Athletes are well represented. In 1952, in a departure from the regular order New York threw a ticker tape parade for the Olympic Athletes leaving for the games in Helsinki Finland. Mayor Impellitteri used the opportunity to make a pitch for New York to host the Olympic Games. (Still a quest.) In 1953 professional golfer Ben Hogan received a ticker tape parade after winning the British Open. Boxer Sugar Ray Robinson was greeted by big crowds at City Hall and at Harlem’s Hotel Theresa when he returned from a European Tour. He was honored both for his boxing prowess and for his contributions of more than $100,000 to cancer research around the world. Olympians were back again in 1984 for what the New York Post termed “the city’s largest ticker-tape parade.” More than 100 medal winners walked up Broadway, showered with paper, including gymnast Mary Lou Retton, basketball player Chris Mullin and bicyclist Nelson Vails. The 1973 National Basketball Association champion New York Knicks didn’t receive a ticker tape parade but instead were honored at a City Hall ceremony. Willis Reed, Earl Monroe, Jerry Lucas, Bill Bradley, Dave DeBuschere all received diamond jubilee medallions that marked the 75th anniversary of the consolidation of New York City in 1898.

Gertrude Ederle aboard the SS Macon, August 27, 1926, in New York Harbor arriving at the Battery for the start of her ticker tape parade. Department of Bridges, Plant & Structures Photograph Collection. NYC Municipal Archives.

Crowds enthusiastically welcomed the first woman to swim the English Channel, Gertrude Ederle, during a ticker tape parade on August 27, 1926, that culminated with an awards ceremony. When she attempted to leave City Hall after festivities concluded, the crowds had not dispersed and pushed forward to get closer. She was rescued by a police officer who carried her back to City Hall. Eventually more officers escorted her home.

One very unusual reception that is documented in the files paired renowned explorer Sir Edmund Hillary, “the lanky New Zealand beekeeper who was knighted by Queen Elizabeth after his conquest of the 29,002-foot peak on May 29, 1953” with Neil Sullivan Jr, “the blind youth, who was the first person ever to score 100 per cent on the comprehensive Regents examinations in music theory,” according to the Herald Tribune.

Cover of dinner program, Imperial Japanese Commission to the United States of America, September 29, 1917. Municipal Library Vertical Files. NYC Municipal Library.

There were diplomats aplenty, from Afghanistan to Venezuela. Dignitaries visits were not always smooth. Mayor John Lindsay refused to welcome French President Georges Pompidou in 1970, creating a tit-for-tat that was smoothed over when President Richard Nixon hosted a dinner in the City for Pompidou and his wife. Mayor Robert Wagner refused to honor King Saud of Saudi Arabia or President Marshal Tito of Yugoslavia and was chided by President Eisenhower who objected to the discourtesy. British Prime Minister Winston Churchill caught a severe cold during his 1952 visit, causing him to miss the scheduled parade up Broadway and medal presentation at City Hall. Instead, Mayor Impellitteri bestowed the honor at Churchill’s bedside and photos were prohibited.

Nelson Mandela addressed the crowds at Yankee Stadium, June 21, 1990. Mayor David N. Dinkins Photograph Collection. NYC Municipal Archives.

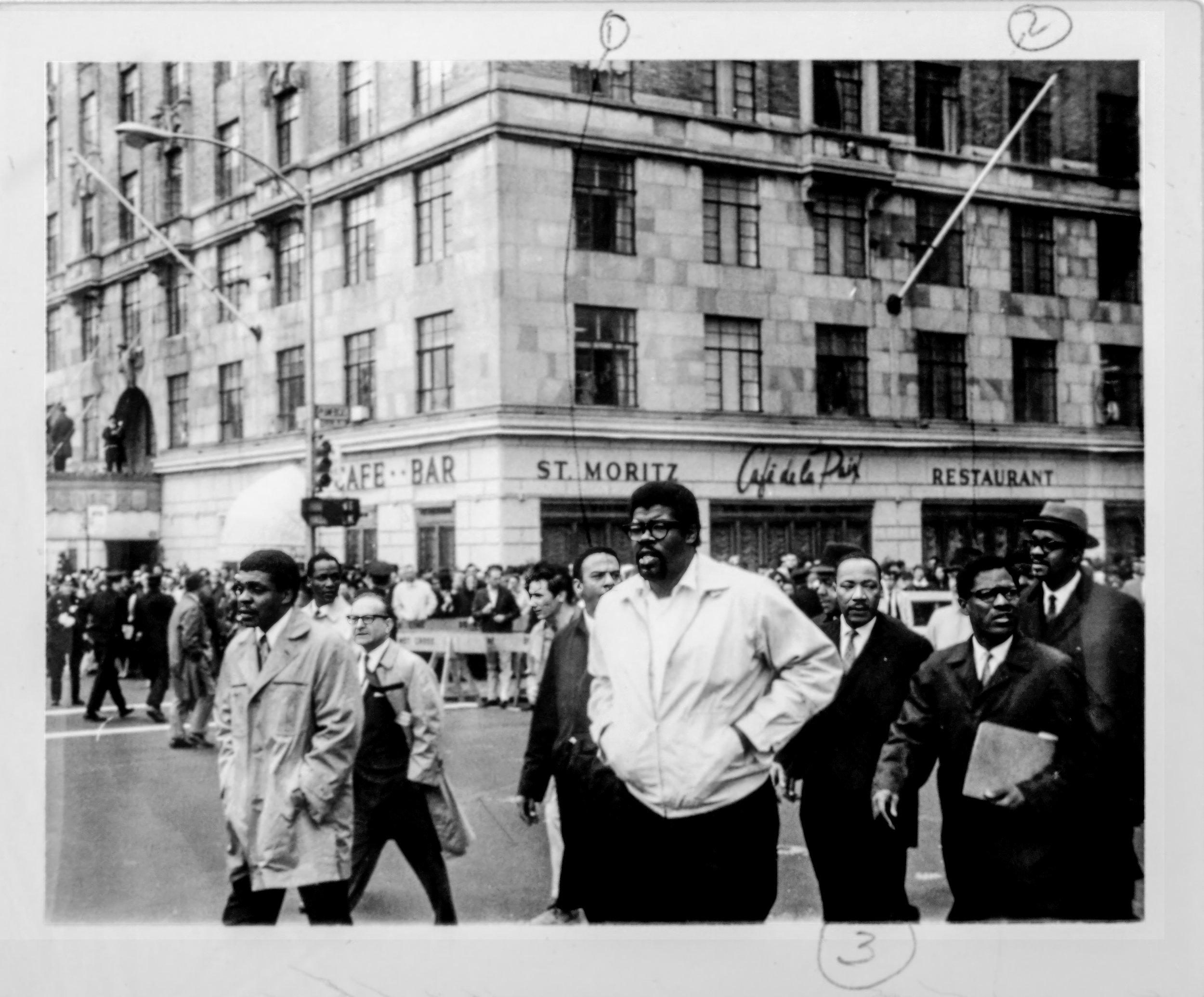

More recently, leader of the African National Congress Nelson Mandela (and later President of South Africa) enjoyed an emotional three-day visit to the City in 1990. Leaving Brooklyn’s Boys and Girls High School, a crowd of people surged onto the route and cheered for him. Along Atlantic Avenue throngs of New Yorkers lined the streets of Bedford Stuyvesant, East New York and Fort Greene. The New York City Police Department estimated that 750,000 people saw Mandela during the New York trip including 55,000 at Yankee Stadium. The visit included a ticker tape parade and City Hall ceremony, numerous receptions a boisterous rally in Harlem, the taping of a TV show, Nightline, at City College, meetings with business leaders, an address to the General Assembly at the U.N., a Riverside Church service, and more.

The receptions and honors also brought the City a bonus. When Pope John Paul II visited in 1995, it was estimated that the trip had a positive economic impact of $44.7 million, including $2.13 million collected in sales tax. The trip launched the Popemobile which transported the Pope through crowds at Giants Stadium the Aqueduct Race Track and Central Park, all sites of papal masses. He wasn’t the first Pope to visit--that honor goes to Pope Paul VI who came to New York to address the General Assembly of the United Nations in 1964. He also met with President Lyndon B. Johnson; toured Queens, the Bronx and Manhattan and offered a Mass at Yankee Stadium—all in less than 14 hours.

The first time Queen Elizabeth II visited, on October 21, 1957, she, too, had a 14-hour whirlwind trip. Landing initially in Staten Island, she took the ferry across the Bay, enjoyed a parade to City Hall, lunch at the Waldorf Astoria, visit to the United Nations, sunset viewing from the top of the Empire State Building, dinner and the Commonwealth Ball at the Armory at Park Avenue and 34th Street. “Cinderella-like, the royal couple will leave the ball at about midnight for Idlewild where their plane is scheduled to leave for England at 12:45 a.m. on Oct 22,” reported Judith Crist in the Herald Tribune.

On her second visit, in 1976, the Queen wined and dined at a more leisurely pace. She also collected a jar of 279 peppercorns which symbolized past due rent paid by Trinity Church. The Church received its charter from King William III in 1697 but neglected to pay the required one peppercorn annual rent until the Queen came to collect.

President Harry S. Truman was reported to be the first President to visit City Hall, in 1945, where he was welcomed by Mayor LaGuardia. Thirty-eight years later, President Jimmy Carter was honored with a reception in the City Council and Board of Estimate chambers after signing the Federal loan-guarantee bill that provided $1.65 billion to help the City avoid bankruptcy.

Although the ticker tape parades are a New York City symbol, they are not entirely beloved. In 1951, the President of the City Council recommended that the receptions and parades be sharply curtailed and that expenses be limited to less than $50 per event. The Herald Tribune reported his comments, “in an economy period there is no need to spend money on holding Receptions elsewhere.” Instead, he recommended standing on the City Hall steps to “shake hands and blow a bugle.”

Events were scaled back during the Lindsay Administration although they did host ticker tape parades for the World Series winning New York Mets in 1969 and the Apollo astronauts. The Commissioner of Public Events was quoted in the New York Times that the ticker tape parades “were horribly expensive and many of them were frauds. The Department of Sanitation was hiring its own people to go up into the skyscrapers and throw out the ticker tape so that the other Department of Sanitation people would have something to sweep up.”

Amidst the schedules and clips about foreign dignitaries, there are also some hometown heroes represented. On September 2, 1964, The Little League World Champions hailing from Staten Island were honored with a parade and ceremony. As was custom, the parade moved from the Battery to City Hall. The Army Band and the Sanitation Department Band both provided music. The sixteen team members, their manager and coach were welcomed by Mayor Robert Wagner and Pitcher, Daniel Yaccarino presented the Mayor with autographed baseballs from the team.

Crowds wading through ticker tape after ticker tape parade for Captain Henrik Kurt Carlsen, January 17, 1952. Municipal Archives Photograph Collection. NYC Municipal Archives.