July is Disabilities Awareness month. This annual recognition dates back to 1990, when President George H. W. Bush signed into law the federal Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA). This landmark legislation prohibited discrimination against people with disabilities. It is estimated that more than 160 million people in the United States live with chronic disease or experience disabilities.

Oyster Boards in the Old Town records

This week’s article highlights another important topic in New York City history that can be researched in the Old Town Records: oysters.

Although somewhat difficult to envision now, two centuries ago, the waters surrounding New York City were clean and fertile enough to provide ample sustenance for the region’s inhabitants. The first European settlers of what became New York City—at the time a scattering of towns and villages across each of the current five boroughs—depended on the land and water around them to survive. One way they accomplished this was to harvest oysters.

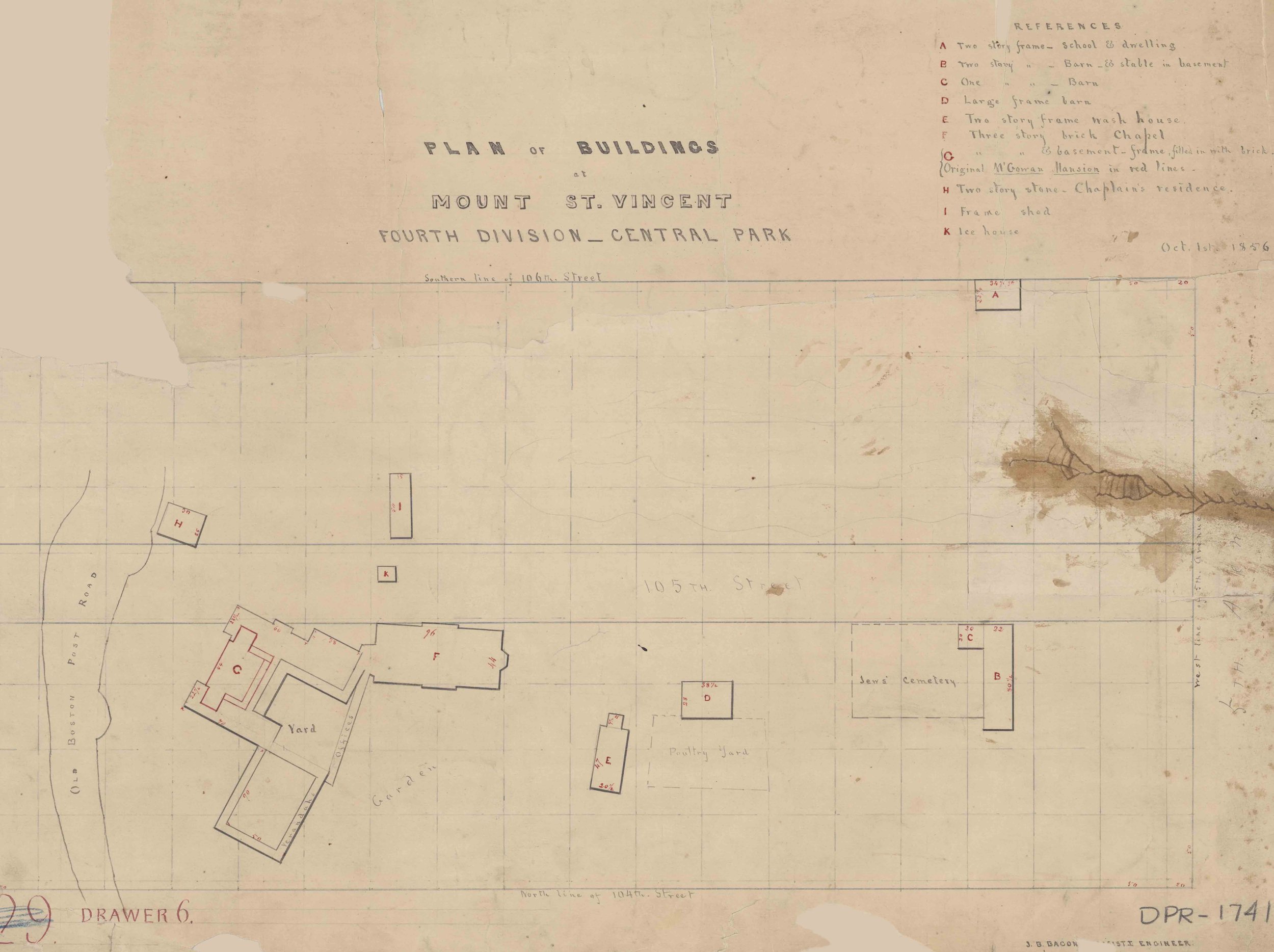

Mount St. Vincent, Central Park

New York City’s parks are open for all to enjoy year-round but the number of visitors skyrockets in the summer season. Those interested in exploring park histories are invited to research Municipal Archives’ collections for information and inspiration. Of these, the most significant is the Parks Drawings Collection which documents sixty parks, parkways, and playgrounds in Manhattan including more than 1,500 drawings of Central Park.

View at Mount St. Vincent, ca. 1863. Photo courtesy Library of Congress.

For the Record has highlighted Central Park drawings in several blogs including Skating in Central Park, The Belvedere Castle in Central Park and Central Park, a Musical Destination for all New Yorkers. This week’s article looks at the area of the park that has the richest history of use and settlement—the quiet and rustic northeastern corner. It is adapted from our book, “The Central Park: Original Designs for New York’s Greatest Treasure.”

Plan of Buildings at Mount St. Vincent, 1856. Parks Drawings Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

Established in 1673, the old Boston Post Road—the original mail-delivery route from New York City to Boston—meandered between two rocky ridges in this area just west of what is now 105th Street and Fifth Avenue. It was here, in the mid-1750s that John Dyckman built a tavern to serve travelers on the road. Not long after, Andrew McGown purchased the land and tavern, running it successfully through the Revolutionary War giving the area its name at the time: McGown’s Pass.

McGown’s Pass Tavern, Central Park, ca. 1905. Photo Courtesy New York Public Library.

The McGown family ran a prosperous business until 1845, when they deeded the land and buildings to the Sisters of Charity of St. Vincent de Paul. The nuns renamed the area Mount St. Vincent’s and within a few years, they established a convent and school. They added a two-story residence for the chaplain to the existing structures, as well as a stately brick convent house that contained a beautiful chapel and large dining rooms. The land also included a small Jewish cemetery. In 1856, before the nuns had consecrated their new chapel, they received word that the city would be acquiring their land for the creation of the new park.

Chapel and buildings at Mount St. Vincent, ca. 1865.

The nuns relocated to The Bronx, and their buildings became the early park headquarters. At one point the families of both Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux lived in the premises while the two men had offices in the main building. With the outbreak of the Civil War, the US government took over the complex for use as a hospital for wounded soldiers who were, curiously enough, tended by the same Sisters of Charity who had previously owned the buildings.

Mount St. Vincent Art Museum, 1863. Parks Commission Annual Report, NYC Municipal Library.

After the war, the main building returned to its original use when it was leased as a restaurant, while the chapel was transformed into a museum until it burned down in 1881. Two years later, the Mount St. Vincent Hotel, based on designs by Julius Munckwitz, was built on the site. The new building proved to be immediately popular with wealthy New Yorkers, as the New York Times reported in 1886: “No matter how fast the team nor how elegant the equipage a turn ‘on the road’ is not done in proper shape unless it includes a bite or a sip in the Mount St. Vincent.”

Mount St. Vincent, Central Park, Design for a Refreshment House, 1883. Julius Munckwitz, Architect. Parks Drawings Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

Mount St. Vincent, Central Park, Design for a Refreshment House, 1883. Julius Munckwitz, Architect. Parks Drawings Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

Now that it was a playground for drinking and dancing for the city’s elite, the Sisters of Charity asked that their name no longer be associated with the establishment. Renamed for the family most associated with the site, McGown’s Pass Tavern remained a popular destination through the turn of the century, but as automobiles replaces horse and carriages the business took a downturn. In 1915, Parks Commissioner Cabot Ward felt that the location would be better suited for a police station. Owner Max Boehm was ordered to vacate the premises and its contents were put up for auction. While the police station was never relocated to area, in 1917 the building was torn down. In more recent history, the location of the former convent, tavern and swanky hotel is now the home of the Central Park composting operations. Throughout the year, fallen leaves and branches are brought here and turned into nutrient-rich compost, which is used for plantings and horticultural projects throughout the Park.

Take a few minutes to view some of the exquisite drawings of Central Park in the gallery.

The Genealogical Possibilities of Manumissions in the Old Town Records

The Department of Records and Information Services is currently digitizing New York colonial and early statehood administrative and legal records dating from 1645 through the early 1800s under a grant generously funded by the National Historical Publications and Records Commission. The records pertain to Dutch and English colonial settlements in New York City, western Long Island, and the lower Hudson Valley.

Families have a sense of themselves. Who they are, where they came from, how they came to be the group they are now. It’s a sense of identity. Many African Americans today are exploring their genealogy but can only go so far because of the legacy of slavery in America and a past obscured by the lack of records. However, there are records in the Municipal Archives that might help fill this knowledge gap. One collection is the Old Town Records, which includes documentation of manumissions and slave births in New York City. While the information may not be new, access to it over the years has been limited. This is changing thanks to a new digitization project. With a grant from the National Historical Publications and Records Commission (NHPRC), the Municipal Archives has been processing the collection. It is comprised of records created in the villages and towns that were eventually consolidated into the Greater City of New York in 1898. They date back to the 1600s and consist of deeds, minutes from town boards and meetings, court records, tax records, license books, enumerations of enslaved people, school-district records, city charters, and information on the building of sewers, streets and other infrastructure.

Manumission of Benjamin Matt by Jacob Hicks, March 4, 1817. Old Town Records, NYC Municipal Archives.

“Manumission” is a legal term that is similar to “emancipation” but slightly different in the way it was performed. Manumission refers to the legal release of enslaved people when slavery is still sanctioned by law, as opposed to emancipation, which follows abolition and releases all people formerly enslaved. Most slave manumissions were conferred by slaveholders who released their slaves either by a living deed of gift or last will and testament. For the Record examined the subject in The Slow End of Slavery in New York Reflected in Brooklyn’s Old Town Records. Additionally, several collections in the Municipal Archives contain records documenting enslaved people, notably the Common Council Papers. A sampling of NYC Slavery Records can be viewed online in “From the Vaults.”

Manumission of Nancy by Jeremiah Remsen, June 30, 1820. Old Town Records, NYC Municipal Archives.

Manumission of Betsey by Gerreta Polhemus, August 29, 1820. Old Town Records, NYC Municipal Archives.

More than 11,000 pages from the 189 Old Town Ledgers have been digitized to date. The digitization is 20% complete and the final count will be exponentially higher at the project’s end. This process can seem slow at times, requiring care for the material that’s being worked on. Sometimes there are opportunities to review the books being worked on and sometimes the entries stick out. This was the case with many manumissions as they were digitized for the collection. Individual names of former slaves along with their former owners are in plain ink on the pages—their lives dramatically changed so many years ago. Most manumissions are only a few simple lines of text, yet their ramifications are so powerful.

Manumission of Sylvia by John Van Nostrand, April 10, 1799. Old Town Records, NYC Municipal Archives.

I’m not African American but I am a New Yorker. I’ve lived in Brooklyn for over twenty years and am familiar with the city’s history. I was aware of the city’s past connections to slavery but I had never seen written evidence of it until I began digitizing the records of places I walk through so often—Bushwick, Gravesend, Sheepshead Bay and other locations. People of all heritages live in these places now, but at the time the manumissions were written these were small farm towns and slavery was common. It is easy for that past to never come to mind; it’s a stretch of imagination to envision the humble towns they were when walking in the urban centers they have become. But that past is very real and the people in the Old Town Records Collection walked many of the same streets we walk today. It is possible their distant relatives may also tread those same streets and not know the connection to their past.

I recently saw similar records of emancipation change how a person thought about herself. After I had been digitizing this material during the day I put on Finding Your Roots, a popular TV show about genealogy on PBS. [https://www.pbs.org/weta/finding-your-roots/] The program has aired over eight seasons and has previously consulted the Municipal Archives to research its guests’ histories.

Manumission of Phillis by Joseph Fox July 11, 1812, and Dianna Orange by Nicholas Beorum, April 12, 1813. Old Town Records, NYC Municipal Archives.

Manumission of Cornelia Brown by Andrew Mercein, April 13, 1813. Old Town Records, NYC Municipal Archives.

This was an episode that featured the musician/actress Queen Latifah and as the story of her heritage unfolded she found some of her ancestors had been manumitted from slavery. The documents presented on the show were from another state and another archive but their value was the same as the lines of text I had digitized during the day. It was freedom; it was another life; it was a new beginning for that person and their family. Those events occurred so long ago and as Queen Latifah read out the words for the camera she had no idea this had ever happened. [https://www.pbs.org/weta/finding-your-roots/watch/extras/queen-latifah-meets-the-woman-that-freed-her-ancestors]. As she talked about what she read she noted that it changed the way she thought about herself, her own personal struggles and how she thought of her family. She was eager to share that information with the people she holds dear. Her whole family would see their history differently. They would see themselves differently. A family that didn’t previously know their past, a family that didn’t know with whom or when their freedom came would now have an entire history opened up by a few lines of writing found in a book in an archive. As the TV show played I reflected on the digitization I perform and knew the same impact is possible through the Old Town Records Collection. The way entire families see and know themselves could shift in an instant from the few words the Municipal Archives makes electronically accessible.

Many things shape family identity but few are as profound and long lasting as information. Personal past. Collective past. They can shape who you are, who you think you are and who you can be. Who an entire family can be. The wider availability of the Old Town Records Collection has the potential to do that for so many families who research their genealogy. We can look forward to more Americans finding themselves.

Manumission of Margarett by Anna Vanderbilt, September 4, 1820. Old Town Records, NYC Municipal Archives.

Grog, Punch and Wine: New Yorkers Celebrate Independence Day

New Yorkers have been celebrating Independence Day since July 4, 1777. Or, have they? Municipal Archives collections are extensive and said to provide documentation on any topic in New York City history. However, there is one notable gap in the holdings. Municipal government was suspended during the period of British occupation from 1776, until the last troops left from the Battery on November 25, 1783. The existence and/or whereabouts of any administrative records for that period has been the subject of speculation ever since. For the Record examined the subject in The Missing Common Council Records of the Revolutionary War.

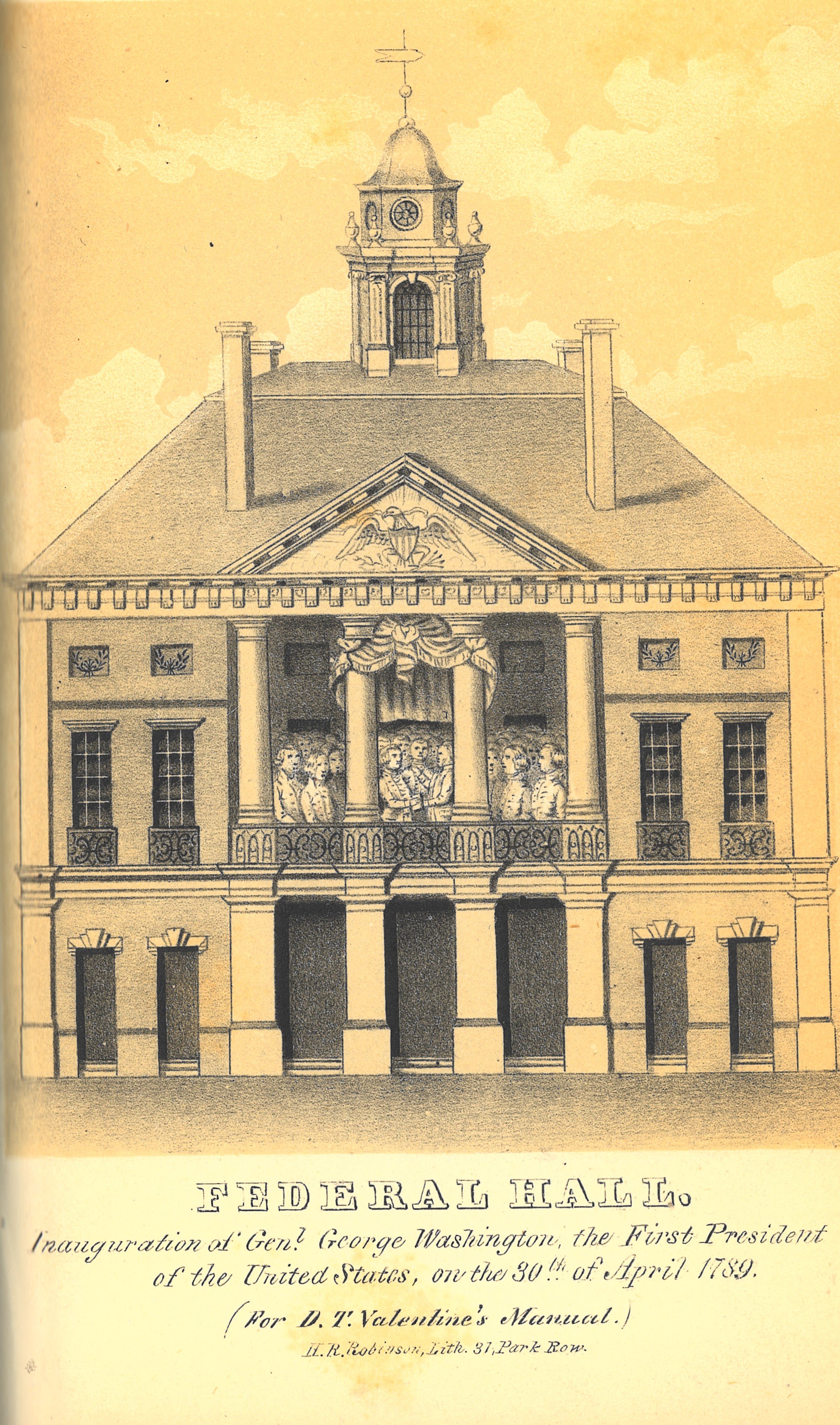

City Hall, Valentine’s Manual, 1852. NYC Municipal Archives

Researchers are not entirely without information about the city during the first decades of the new republic. The six-volume Iconography of Manhattan Island, by Isaac Newton Phelps Stokes, helps fill the documentation gap. Stokes relied on newspaper accounts and other sources, as well as the Minutes of the Common Council, to write a daily chronicle of key events in city history from 1498 to 1909.

Federal Hall, 1789, Valentine’s Manual 1849. NYC Municipal Archives

The Municipal Library collection includes the Iconography and looking at entries during the Revolutionary War period reveals that Philadelphia celebrated the first “Anniversary of the Independence of the United States of America,” in 1777. It is possible to imagine that at least some New Yorkers also managed to celebrate Independence Day, quietly, but Stokes makes no mention of festivities in New York City during the occupation.

Municipal government reconstituted in 1784, and the re-convened Common Council held its first meeting on February 10. When municipal government restarted, so too, did record-keeping in the form of the Minutes of the Common Council. The Minutes and the related series, Common Council papers, are two of the most essential collections in the Municipal Archives.

There is a useful cumulative index to Minutes of the Common Council covering the period 1784 through 1832. Reviewing the entries for “Fourth of July,” shows the first mention of a celebration in 1785: “…That Alderman Broome & Bayard & Mr. Lawrence and Mr. Ten Eyck be a Committee to report the Measures proper to be taken by this Corporation on the Fourth of July; being the 9th anniversary of the Independence of this State.” (Common Council Minutes, 22 June 1785.)

The Committee to Report the proper manner of celebrating the 4th of July next (partial text), Minutes of the Common Council, June 21, 1796. NYC Municipal Archives

The Council established similar committees, on an annual basis, through at least the first several decades of the 19th century. In 1786, the appointed committee reported to the Council on the arrangements for Independence Day: “That at sunrise the day be announced by a display of colors, a discharge of 13 Cannon & the ringing of all the public Bells for one Hour. That at 12 O’clock there be a Procession of this Board & other public Officers & the Citizens from the City Hall down Broad Street & through Queens Street to the Residences of their Excellencies the Governor & the President of the United States and thence by way of Beekman Street to the City Tavern where a Collation be provided…” (Common Council Minutes, 28 June 1786.)

Warrant to Daniel Phoenix, Treasurer, for payment of twelve Pounds for the ringing of the bells on the 4th of July, 1795. Common Council papers. NYC Municipal Archives.

Warrant to Daniel Phoenix, Treasurer, for payment of twenty-five Pounds for illuminations and fireworks on the 4th of July, 1795. Common Council papers. NYC Municipal Archives.

In 1789, according to Stokes, “The presence of [President George] Washington in New York makes the celebration of Independence Day especially noteworthy.” Unfortunately, as Stokes reports, Washington had been suffering an illness which “…Deprived the troops of the honor and satisfaction of being reviewed by him in the field.” But later in the day “…they passed the house of the President… who appeared at his door in a suit of regimentals, and was saluted by the troops as they passed.” In the afternoon, a concert in St. Paul’s church was “honored by the presence of the First Lady and Family of the President, his indisposition (the inconvenience of which thanks be to Heaven, are nearly surmounted) prevents his personal attendance.”

The related series, Common Council papers, also provides information about Independence Day celebrations. The series consists of documents written by or presented to the Council. The date span of the entire series is from 1670 to 1934. However, the material after 1870 consists primarily of resolutions with little supporting documentation. From 1800 to 1831, the documents are separated by year into folders generally pertaining to the standing and special committees created by the Council, e.g. Arts, Sciences & Schools, Charity & Almshouse, Fire & Water, Lamps & Gas, Police, Watch, Prison, Streets, Wharves, etc. The folders are arranged alphabetically. With funding from the National Endowment for the Humanities, the Municipal Archives processed and microfilmed the Common Council papers.

Invoice for payment for punch, grogg, wine, etc., July 4, 1793. Common Council papers. NYC Municipal Archives

The papers helpfully include warrants for payment to vendors who supplied services for Fourth of July celebrations. In 1795, Captain Bauman’s bill for “…illuminations & fireworks… on the celebration of the late anniversary of American Independence,” amounted to twenty-five pounds.

In 1793, John Simmons’ bill for four large bowls of punch, nine bowls of grog, thirty bottles of wine, plus coffee, crackers, etc. came to twenty-six pounds, nine shillings and six pence. What is less clear is who consumed the beverages. Perhaps this is typical of the “collation” referred to in the 1786 Minutes. In any case we will assume they enjoyed the celebration.

From For the Record, wishing everyone a happy Fourth of July!

New York City Celebrates Pride

On Sunday, June 26th, New York City will host Gay Pride, the yearly celebration of the LGBTQ community. The first parade took place on June 28th, 1970, on the one-year anniversary of the uprising at the Stonewall Inn which galvanized the modern gay rights movement. Since then, New York has staged an annual Pride march—one of the largest in the world—typically during the last weekend of June.

After last year’s largely virtual affair, this NYC Pride celebration promises to be a mix of both in-person and virtual events. The parade route will kick off at noon on 5th Avenue at 26th Street, then proceed downtown before heading west on 8th Street. After crossing over 6th Avenue, it will continue on Christopher Street passing the Stonewall National Monument. It will then turn north on 7th Avenue, passing the New York City AIDS Memorial, before ending at 16th Street and 7th Avenue.

Before you head out to the parade, take a moment to review a gallery of photographs from the 2019 parade. That year, an estimated 150,000 marchers celebrated the 50th anniversary of Stonewall.

All photographs by Aburaihan Rahman, External Affairs Associate, Department of Records and Information Services, June 30, 2019.