May Day, or International Worker’s Day, originated during the 19th century in the United States, but observance in this country has greatly diminished in recent years. Labor Day is more widely celebrated to commemorate the strides made by labor activists. As recently as the 1970s, however, May Day marches took place in New York. The Municipal Archives New York Police Department (NYPD) Special Investigations Unit collection includes documentation of parades during that era.

May Day flyer, 1955. New York Police Department Intelligence Records, Hanschu Small Organization Series. NYC Municipal Archives.

This Week, For the Record highlights the NYPD May Day records as well as other collections in the Municipal Archives that are useful for labor history research. In addition to the NYPD material, the Building Department permit collection, felony prosecution records, and mayoral correspondence are all good sources.

May Day was born on May 1, 1886, when the American Federation of Labor (AFL) urged all workers to strike for an eight-hour day. Workers in Chicago heard the call and launched a strike that was met with a heavy police response. Known as the Haymarket Affair, an unknown person detonated a dynamite bomb, prompting police officers to open fire on striking workers. The AFL established May 1 to commemorate Haymarket and the continuing push for an eight-hour workday. The holiday soon spread throughout the world.

Labor activism has a long history in New York City. Some of the largest labor demonstrations, as well as legislative changes that eventually improved working conditions, occurred in New York. One of the earliest labor unions established in the U.S. was the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union (ILGWU). Founded in New York City in 1900, the group was the fusion of multiple local unions. They organized numerous large-scale strikes involving tens of thousands of industrial workers, particularly in New York City’s garment district which was notorious for its brutal sweatshops. Workrooms were overcrowded, dimly lit, and workers were underpaid and overworked. By 1910, the ILGWU won concessions that improved safety in those settings.

The Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire in 1911 proved that more measures were desperately needed. It remains one of the deadliest disasters in New York City history. Located in Greenwich Village at 23 Washington Place, the factory exhibited many of the deadly conditions experienced by the largely immigrant garment workers. The factory did not have proper fire escapes. In addition, poor ventilation and locked exits prevented the workers from escaping the flames and smoke. The single fire escape on the building collapsed, the main doors were locked or jammed, and the main exit was limited to only a few employees at a time. Ultimately this led to the deaths of 146 garment workers, mostly young immigrant women.

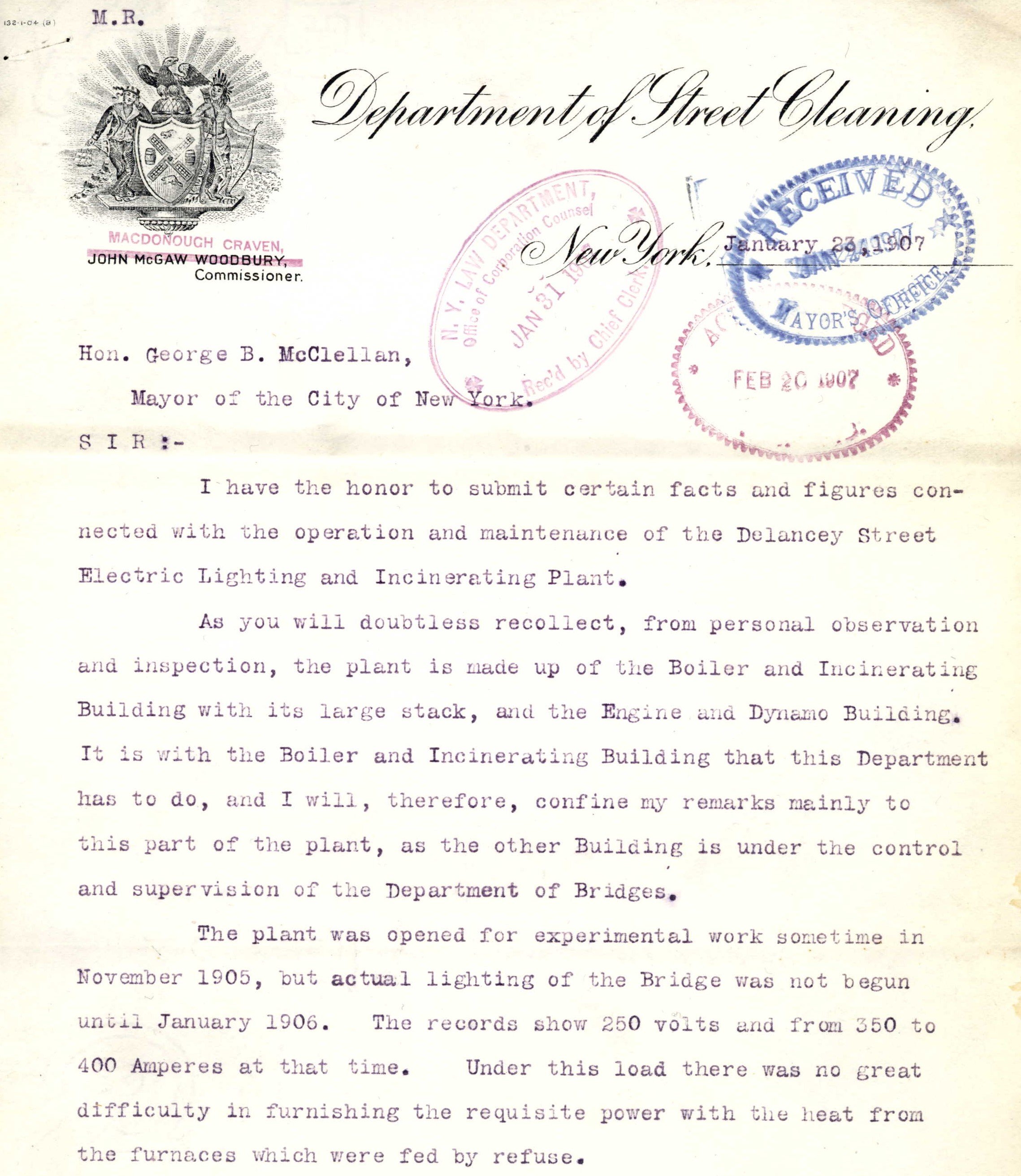

Two Municipal Archives’ collections document this tragic event. The Manhattan Department of Buildings block and lot permit collection includes correspondence related to 23 Washington Place. In a letter dated May 6, 1900, building architect, John Wooley, requested an exemption from the building law to require fewer staircases for escape.

Correspondence, Manhattan Block 547, Lot 8, 1900. Department of Buildings, Manhattan permit folder collection. NYC Municipal Archives.

The Archives’ New York District Attorney felony prosecution records include the indictment against factory owners Max Blanck and Isaac Harris. Prosecutors presented evidence that showed that the doors were intentionally locked during working hours to increase productivity, and that exits were restricted to prevent employees stealing scraps of cloth, and allegedly to prevent union organizers from entering the factory.

Felony Indictment no. 82980 of 1911, New York District Attorney collection. NYC Municipal Archives.

Felony Indictment no. 82980 of 1911, New York District Attorney collection. NYC Municipal Archives.

Blanck and Harris were acquitted of manslaughter, but eventually, in 1913, they were found guilty in a wrongful death civil suit. The ruling forced the owners to compensate each affected family with $75.00.

The fire mobilized the ILGWU to fight even harder for better working conditions in the city, and ultimately in the country. Local leaders like Frances Perkins eventually helped shape policies of the New Deal in the 1930s and 40s.

Other Municipal Archives collections are useful for research into the labor movement. Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia’s papers are a good source of information about the American Labor Party (ALP). Founded in 1936, and operated largely within New York, it was closely aligned with President Franklin D. Roosevelt. LaGuardia’s records include his correspondence with the ALP. One example is the ratification of the ALP’s state legislative program. The ALP sent advance copies of the report directly to the Mayor’s Office for comments.

Correspondence, Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia Subject Files, 1945. Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

Correspondence, Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia Subject Files, 1945. Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

Mayor LaGuardia and New York State officials, worked closely with the ALP to give unions and trade groups more protections. The interconnectedness of labor groups and the local government showcases the strength of the pro-labor movements in the first half of the 20th century.

The Cold War and growing fear of Communism ultimately led to the dissolution of the ALP. But even as the party lost power, other groups rose up to take its place. Throughout the second half of the 20th century, organizations formed to advocate for workers rights, better union representation, and for peace in the world.

The recently processed New York Police Department Intelligence Records highlights these groups and their activities. Parades featuring speakers, activities, and entertainment were one way to gain attention. They were meant to engage with New Yorkers and bring awareness to social causes. Here is a flyer and press release from an event hosted by the Provisional Workers and People’s Committee in 1955.

May Day Press Release, 1955. New York Police Department Intelligence Records, Hanschu Small Organization Series. NYC Municipal Archives.

May Day flyer, 1955. New York Police Department Intelligence Records, Hanschu Small Organization Series. NYC Municipal Archives.

The origins of May Day are still remembered almost 150 years after the Haymarket Affair, and the lessons of the first labor activists echo in their rallies today. Whether participants are fighting for a four-day work week, an eight-hour workday, greater representation in government, equal pay or higher wages, May Day is a milestone—somewhat diminished from its heyday—but still observed in New York City.

Researchers are welcome to contact and visit the Municipal Archives to learn more about our collections that highlight labor history in New York City.