New York City is an archipelago of islands. Of the five Boroughs, only the Bronx is connected by land to the continental United States. When temperatures rise many New Yorkers naturally gravitate to the 520 miles of shoreline along the rivers, bays and ocean that surround the city. Or would, if they could.

In recent years, sections of the waterfront have been reclaimed for housing and recreation; Brooklyn Bridge Park and Hudson River Park are two notable examples. But from the days of the first Dutch colonial settlement in the 1600s, until the 1960s, most of the waterfront had been virtually inaccessible except to those involved in the commercial maritime activities that had been the basis of the city’s economy. And if not consumed by docks, piers, factories and other structures, transportation arteries – railways, parkways, and highways – girded many more miles of the waterfront, further impeding access.

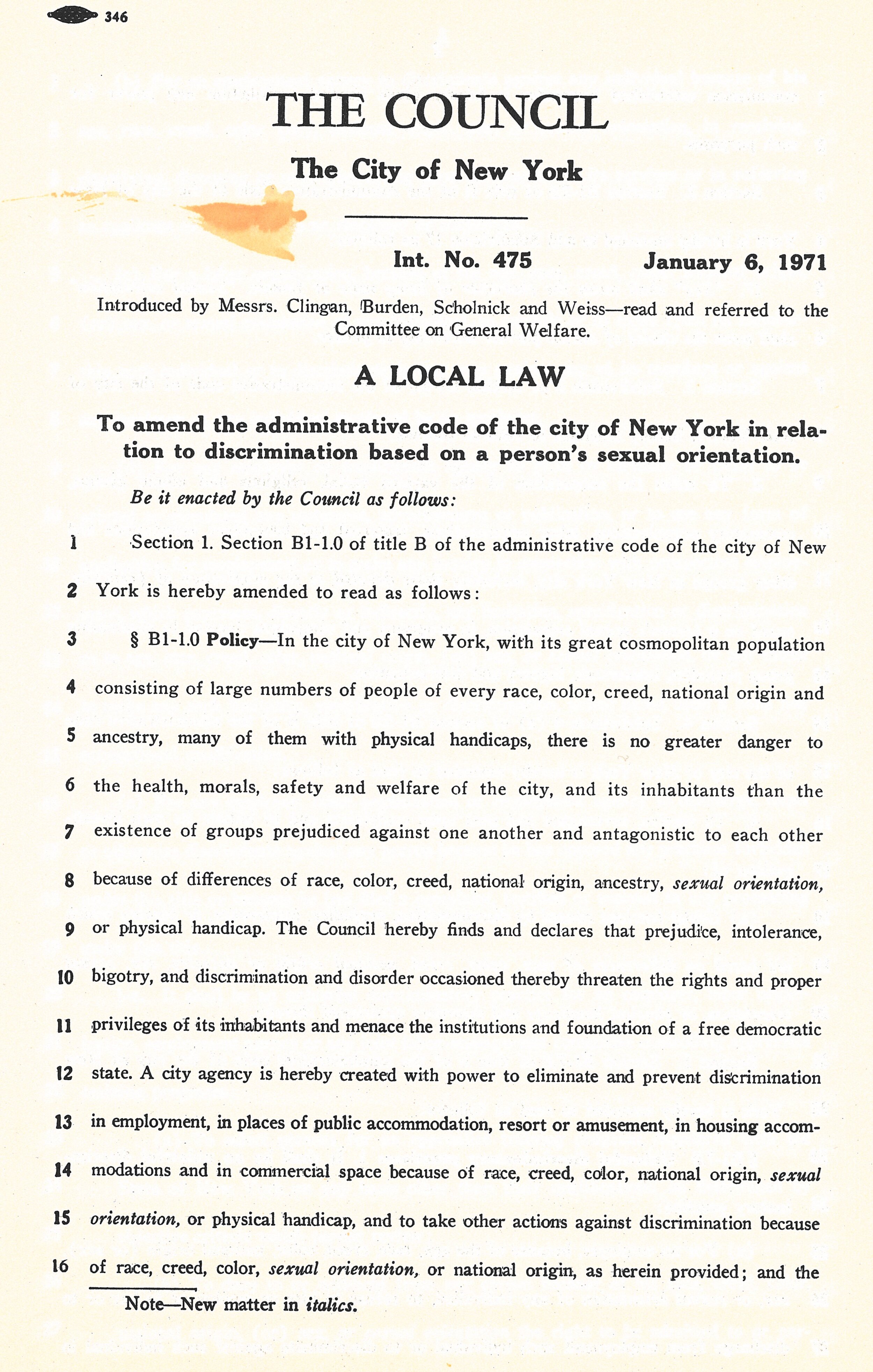

The Municipal Archives collections includes extensive documentation of the City’s investment in its waterfront. The records date from the earliest years of the Department of Docks (1870– 1897); Docks and Ferries (1898 -1918); Department of Docks (1919-1942); Marine and Aviation (1942-1977); Ports and Terminals (1978-1985), through its final iteration, the Department of Ports and Trade (1986-1991). These series offer hundreds of cubic feet of maps, surveys, official correspondence and photographs.

Here are some of the more evocative images of New York’s working waterfront in its glory days.

The Department of Docks photograph collection includes numerous large-format glass-plate negatives that depict the intense commercial activity along both the East and North (Hudson) River waterfronts. West Street, ca. 1922. Department of Docks Collection. NYC Municipal Archives.

Teams waiting at East 35th Street for the ferry to Brooklyn, November 1910. Department of Docks Collection. NYC Municipal Archives.

Dozens of steamship lines brought hundreds of thousands of immigrants to the United States via New York City. Italian Line, West 34th Street, 1903. Department of Docks Collection. NYC Municipal Archives.

Not every inch of the waterfront was devoted to commercial activities. In 1897, the Department of Docks built the first Recreation Pier at Corlear’s Hook in Manhattan; others were added on the East River at 112th Street, and the Hudson River at Christopher Street and 50th Street. Designed in the French Renaissance style they featured seating for 500 on the second floor and typically offered musical entertainments and food concessions. Recreation Pier Rendering, undated. Department of Docks Collection. NYC Municipal Archives.

Recreation Pier. The sign over the entry doors reads: “Dancing on this Pier for Children from 3 to 5 p.m. Daily Except Sunday." Recreation Pier, undated. Department of Docks Collection. NYC Municipal Archives.

The Cty began building the East River Drive in 1929 and the West Side Highway in 1931. By the time master builder Robert Moses finished construction in the 1950s, multi-lane arterial highways would line the waterfronts of four of the five Boroughs. Elevated Public Highway, looking south from Duane Street, June 23, 1937. Borough President Manhattan Collection. NYC Municipal Archives.

Completed in 1910, the Chelsea Piers along the Hudson River between Little West 12th Street and West 23rd Street were built to accommodate the new Titanic-class of ocean liners coming from Europe. Warren & Wetmore, architects of Grand Central Terminal, designed the pier sheds. Pier 56, Chelsea Piers Elevation, Department of Ports and Trade Collection. NYC Municipal Archives.

In the 1930s, W.P.A. Federal Writers’ Project staff photographed dockworkers loading and unloading cargo on piers throughout the city. By the 1960s, containerization would eliminate thousands of these jobs. Unloading coffee from Brazil at the Gowanus Bay Pier, Brooklyn, ca. 1937. WPA-Federal Writers’ Project Collection. NYC Municipal Archives.

The fishing industry persevered in lower Manhattan until 2005 when it relocated to the Hunts Point Market in The Bronx. Fulton Fish Market, April 14, 1952. Department of Marine and Aviation Collection. NYC Municipal Archives.

By the mid-20th century, New York was one of the worlds’ greatest port cities. At its peak this vast infrastructure extended well beyond lower Manhattan and included miles of Brooklyn’s waterfront. Aerial view of the Brooklyn waterfront near Atlantic Avenue, September 19, 1956. Department of Marine and Aviation Collection. NYC Municipal Archives.

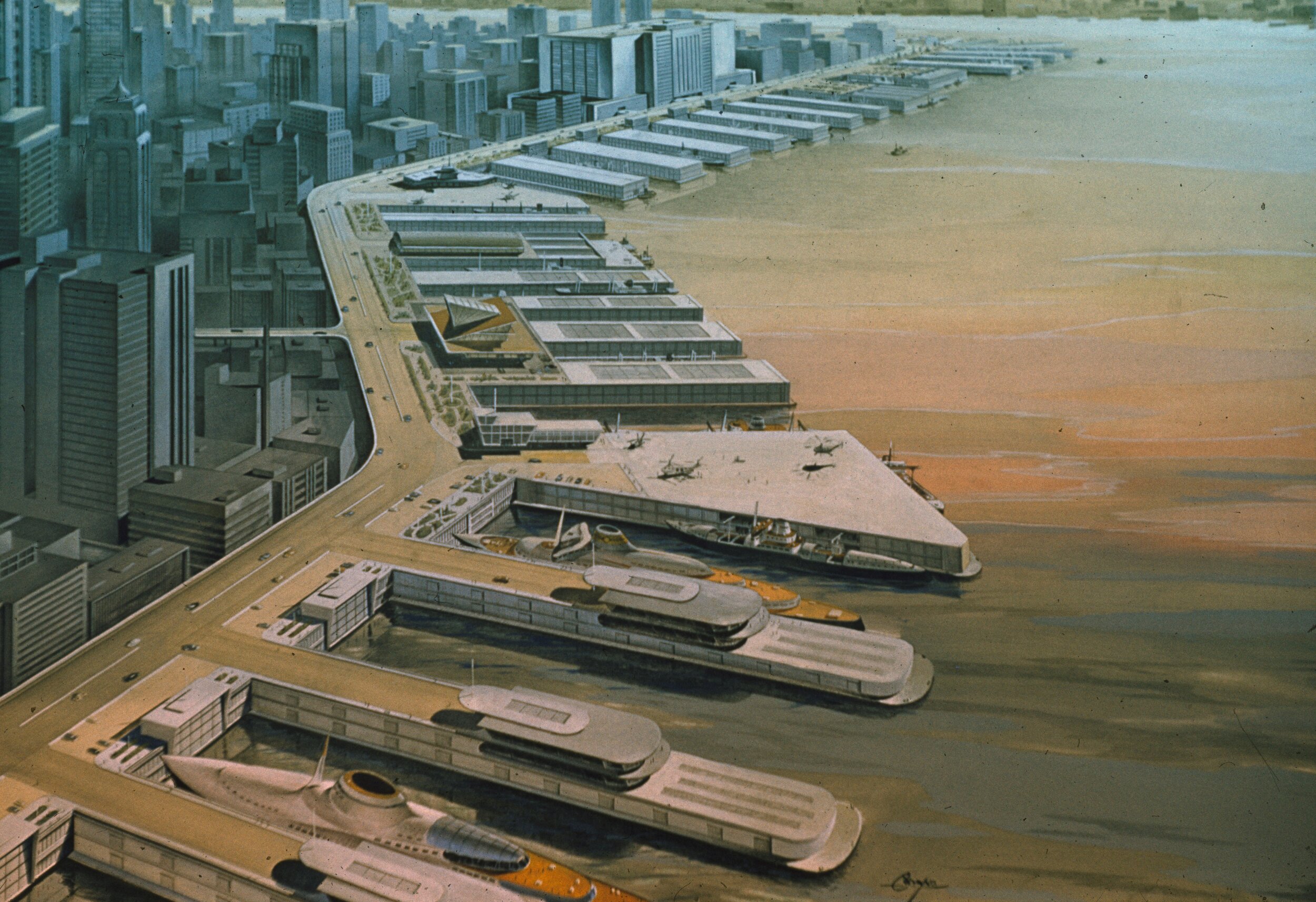

The Department of Marine and Aviation collection includes large format color transparencies. Aerial view, East River, Manhattan, November 5, 1953. Department of Marine and Aviation Collection. NYC Municipal Archives.

Until the advent of jet air service in the 1960s, luxury ocean liners dominated the trans-Atlantic market. The S.S. United States and the S.S. America, New York harbor, April 7, 1963. Department of Marine and Aviation Collection. NYC Municipal Archives.

In the 1960s the commercial cargo industry defected to the Port of Newark in New Jersey which had space to accommodate the mechanized equipment needed to load and unload the containerized shipments. Many of the City’s plans to improve its waterfront infrastructure during that time period went no further than the drawing board. East River, Manhattan, Pier Improvements, Rendering. Department of Marine and Aviation Collection. NYC Municipal Archives.

Perhaps Department of Marine and Aviation Commissioner Edward F. Cavanagh was mourning the end of an era as he watched the arrival of the Queen Mary in New York harbor on February 6, 1953. (Negative damaged.) Department of Marine and Aviation Collection. NYC Municipal Archives.