Before watching the Netflix film Rustin, what I knew about Bayard Rustin, a key organizer and mastermind behind the March on Washington, was limited. I had only seen Rustin’s name mentioned in the organizational files of the New York Police Department (NYPD) Intelligence Records, also known as the “Handschu” collection. However, after a closer examination of the Handschu records, I became aware of Rustin’s prolific involvement with numerous organizations, and his influence on some of the most successful demonstrations in civil rights history.

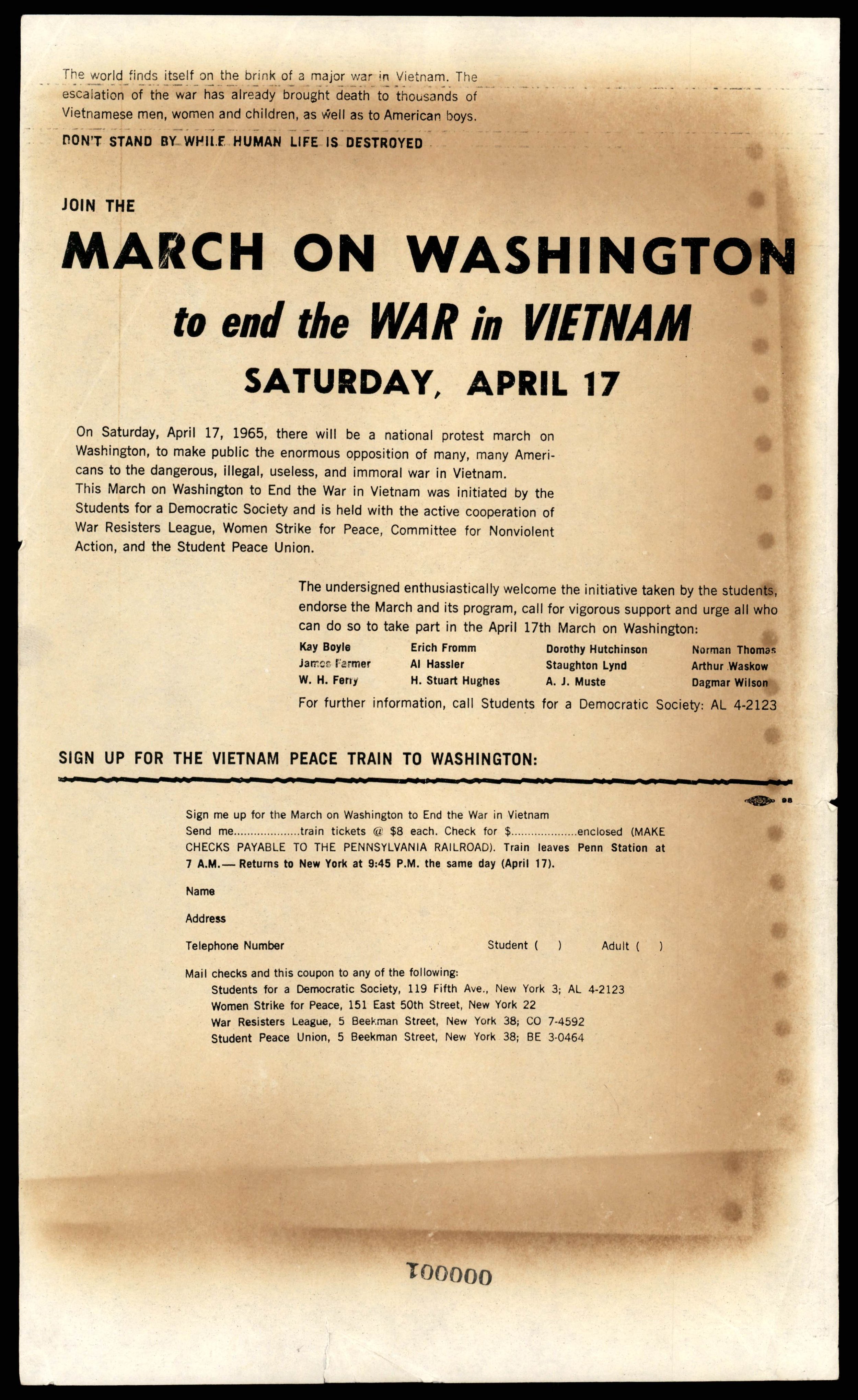

March on Washington, Flyer, 1965. Handschu Collection. NYC Municipal Archives.

The Handschu collection, which contains records acquired by the Municipal Archives as part of Judge Charles W. Haight’s 1985 court ruling in Barbara Handschu et al. v. Special Services Division, is an invaluable resource for information about the city’s social-political sphere during the 1950s-1970s. The collection includes biographical data, mugshots, flyers and reports from several organizations, police complaints and communication reports, surveillance photographs, and audiovisual material. The vast collection comprises around 500 cubic feet, including 200,000 card files and information on more than 5,200 organizations and 3,000 individuals. Thanks to extensive surveillance and documentation of the civil rights movement, the Handschu records are an excellent source of information to learn about civil rights leaders like Bayard Rustin.

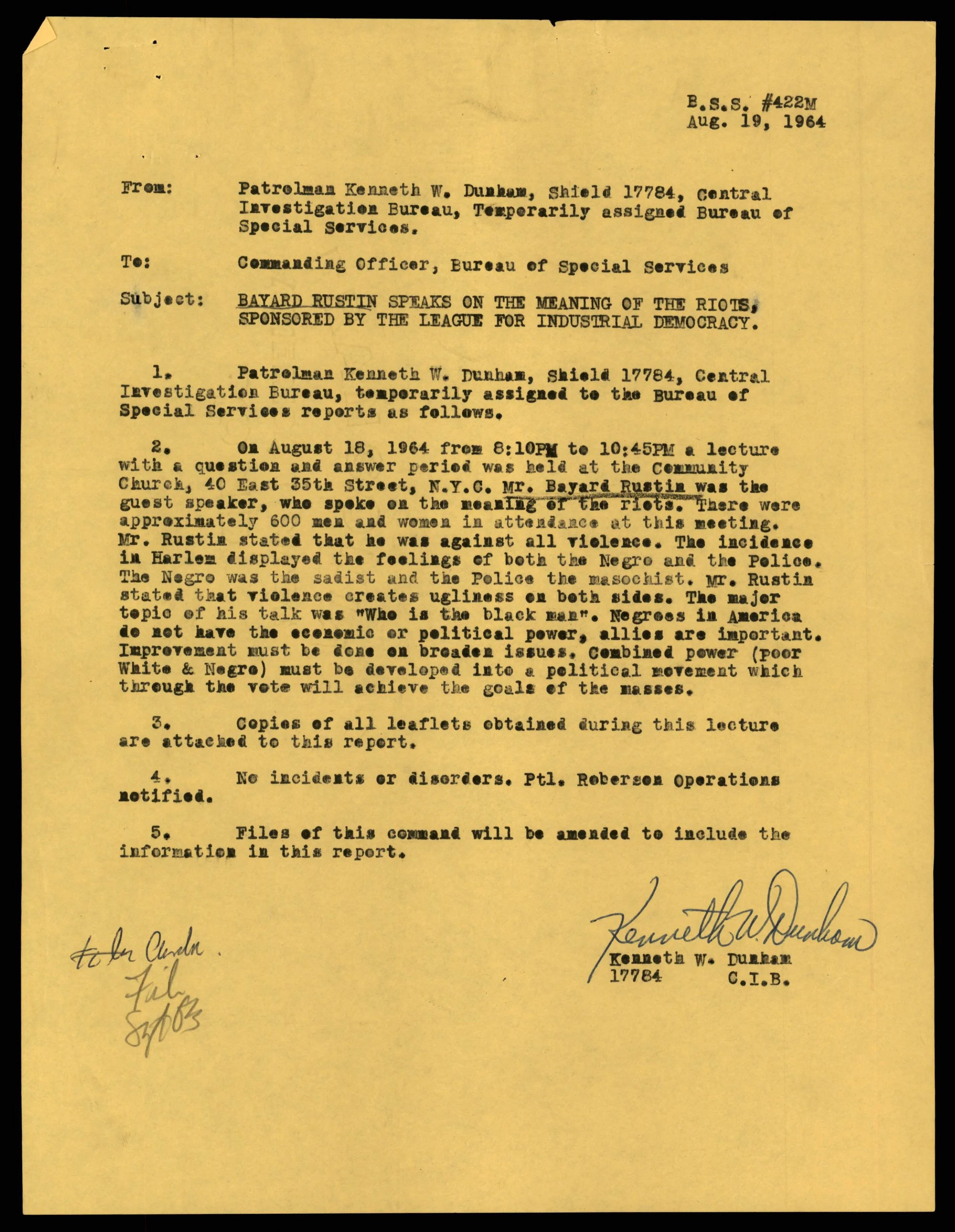

The Handschu collection is comprised of several series, including individual files. Rustin’s file only has an index card that refers to a single communications report concerning his statements about the Harlem Riots in 1964. Although it is not uncommon to find empty files, it is unusual that a file lists only one report.

Report regarding Bayard Rustin, August 19, 1964. New York Police Department Intelligence Files, Bureau of Special Services, Handschu Collection. NYC Municipal Archives.

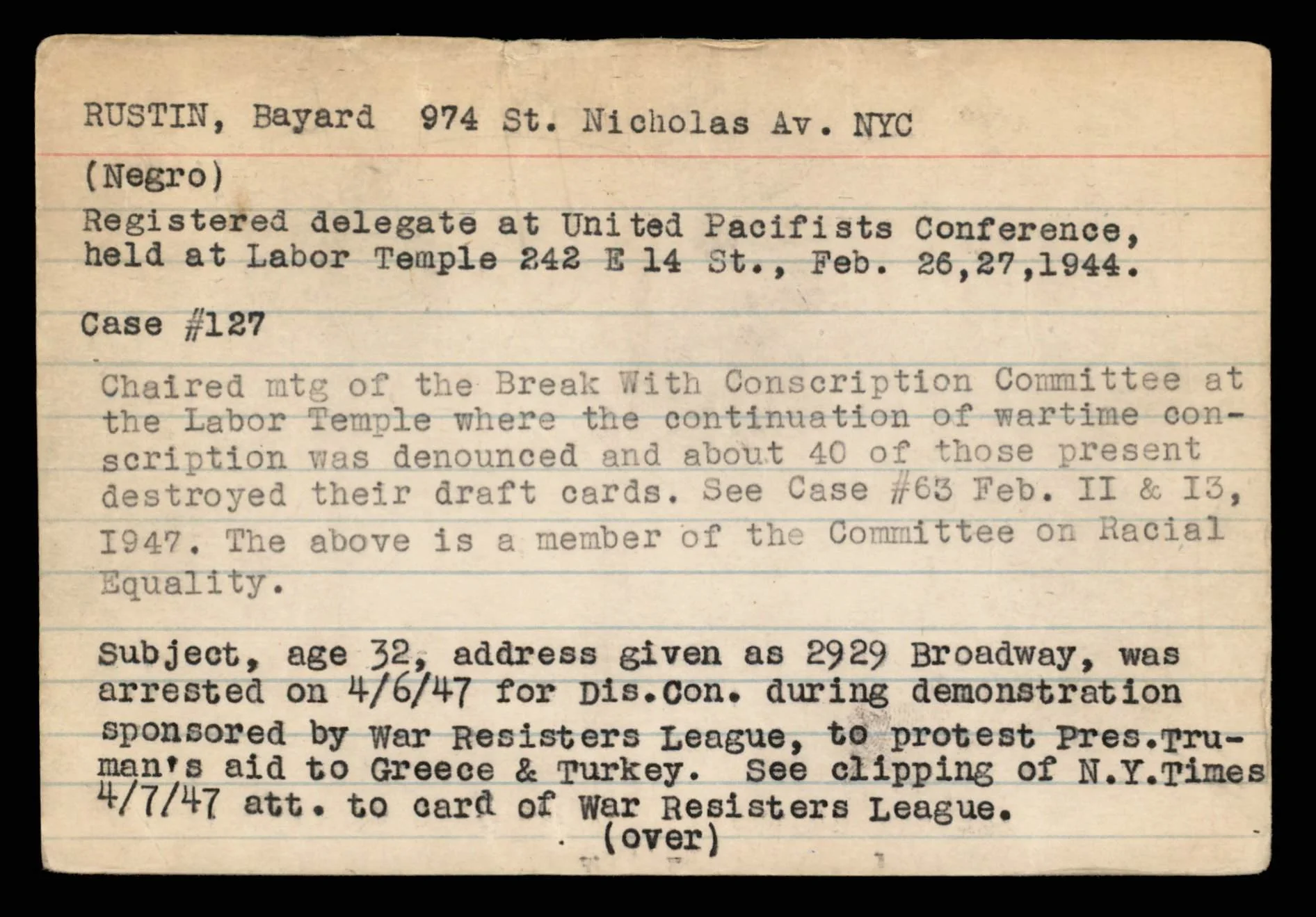

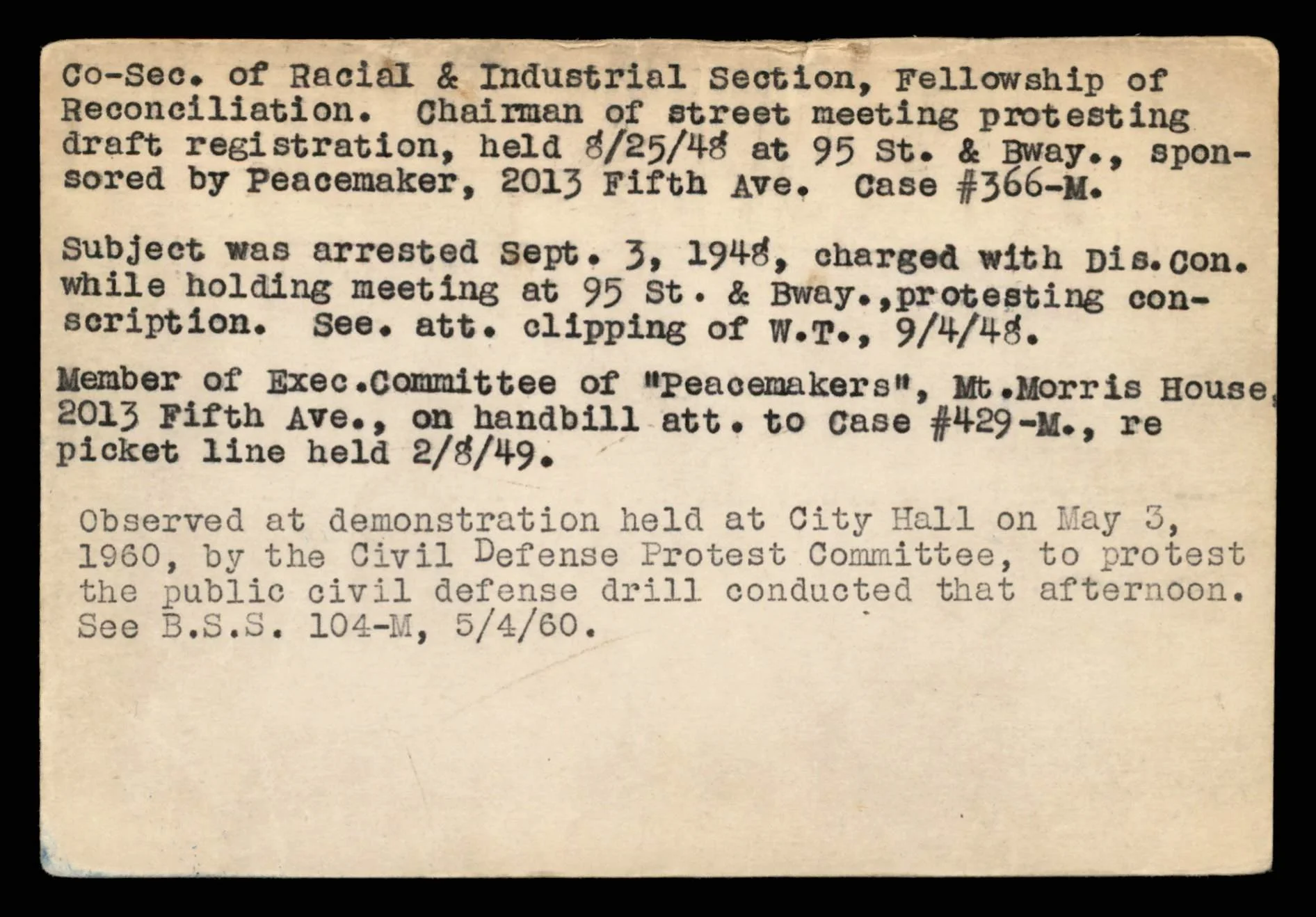

After an unsuccessful search, I reviewed the Handschu card series, arranged by name into various groupings. Each card records the person’s name and includes information such as age, occupation, and relevant political activity. Police officers created the cards as they gathered information about a person, and there can be multiple cards for an individual. Rustin’s card shows us his passion for pacifism and work against conscription. The card comments on his arrests in 1947 and 1948, while working with the Fellowship of Reconciliation. The card lacks references to reports and ends around 1960, which is unusual. There could be multiple reasons for the abbreviated information; for example, state and federal agencies often requested police files for their investigations, and many cards were not returned or were misfiled.

Bayard Rustin, Index Card, New York Police Department Intelligence Records, Bureau of Special Services, Handschu Collection. NYC Municipal Archives.

Bayard Rustin, Index Card (reverse), New York Police Department Intelligence Records, Bureau of Special Services, Handschu Collection. NYC Municipal Archives.

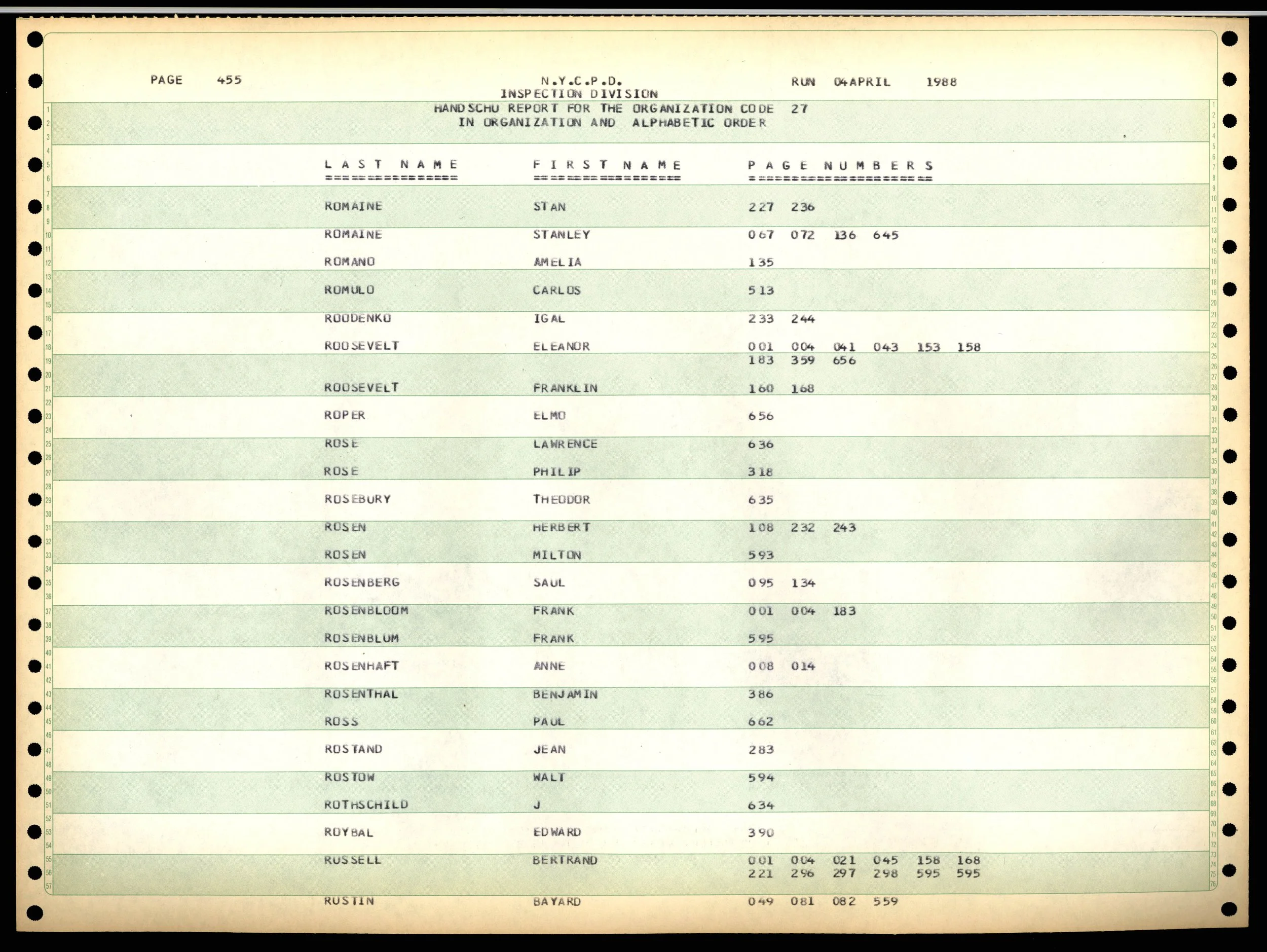

In 1988, the New York Police Department’s Inspectional Services Division decided to index and number the pages of files from sixteen different organizations represented in the large organization series, which includes groups like the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), Communist Party, Black Panther Party, and National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). The indices list the names of individuals along with the page on which the person is mentioned. A sample page for SANE Nuclear Policy, for example, designated organization code 27, lists Rustin, along with other prominent individuals such as Eleanor and Franklin Roosevelt. Rustin appears in twelve of sixteen organization folders, including CORE, NAACP, Black Arts, Communist Party, and Students for a Democratic Society (SDS). His most prominent role was with CORE, an organization he co-founded and was active in for many years. His association with that group generated multiple references.

Large Organization Index, Organization 27 (SANE Nuclear Policy), New York Police Department Intelligence Records, Inspectional Services Division, Handschu Collection. NYC Municipal Archives.

Rustin’s inclusion in these organizations supports the thesis that while he is not yet a household name, he was instrumental in organizing and leading activities that changed the course of American history. Although he was a Deputy Director of the March on Washington, we find only a few mentions of his name in that folder. With more than 250,000 people in attendance, the March on Washington is one of the most well-known civil rights events, and the venue for Martin Luther King’s famous “I Have a Dream” speech. Nevertheless, it was not Rustin’s first rodeo; the organizational files also include his role in organizing the 1958 Youth March for Integrated Schools, which had around 10,000 attendees. Other significant impacts include Rustin’s part in organizing a school boycott along with Reverend Milton Galamison, which resulted in more than 400,000 students boycotting classes and several peaceful rallies across the city in favor of school desegregation.

There are very few details about Ruskin’s personal life in the Handschu files, but we get a sense of his friendship with Martin Luther King. We find him serving as a Special Assistant to Dr. King, listed as Executive Director of the King Defense Committee, and leading a march at a peace rally after Dr. King’s assassination. There are references from individuals in the War Resister’s League files that indicate he was well-liked and admired. Although he was an openly gay man, there is no indication about his sexuality in any of the files. The only mention I found was a New York Tribune clipping discussing Senator Strom Thurmond’s remarks that labeled Bayard Rustin a pervert after the revelation of a 1955 sodomy charge in California. The clipping has the words “Send to BOSS” inscribed in the corner.

Interview with Bayard Rustin, Report, July 20, 1967. New York Police Department, Bureau of Special Services, Handschu Collection. NYC Municipal Archives.

The Handschu records demonstrate that Rustin was actively involved in various causes, including anti-war efforts, fighting discrimination, education, and labor rights. There are numerous examples of his support for improving life for all. For instance, in the War Resister’s League folder, we find an essay where he proclaims that “the Crisis in Vietnam is not only one of the dangers of nuclear war [but] a crisis for the conscience of America.” There is also a flyer listing him as a guest speaker at a community church addressing the murder of four children in Birmingham, Alabama, and a report of a rally and sit-in against Woolworth’s and W.T. Grant stores. In other records, we find evidence of him writing letters requesting donations for the National Economic Growth and Reconstruction Organization (NEGRO) and supporting taxicab strikes.

Rustin believed that nonviolent resistance was the best approach to social change. The most effective way of combating racism and inequality was by cooperating with races and forming powerful alliances. Fortunately, historians can use these intelligence records, which the police created and acquired for surveillance, to piece together the life of a man who significantly impacted the civil rights movement.