Mayor Bill DeBlasio launched the City’s multi-agency Vision Zero initiative in 2014 to improve street safety and reduce the number of pedestrian and biker fatalities. There are now 1,375 miles of bike lanes in the City and Vision Zero has led to a reduction in pedestrian fatalities and how City streets are utilized.

Greater New York Merchants’ Association Bulletin, Feb. 11, 1924. Mayor Hylan Collection. NYC Municipal Archives.

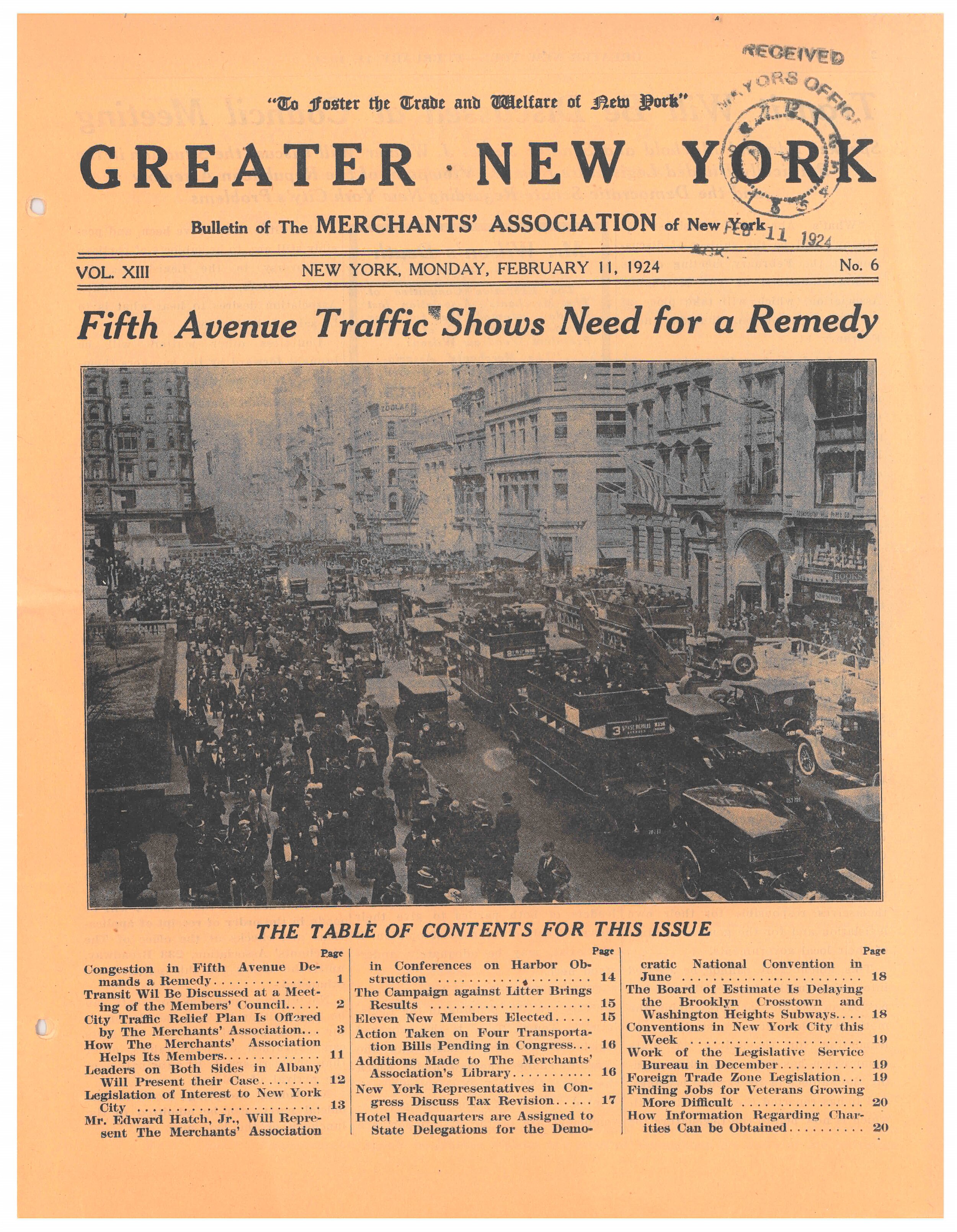

It may not be a surprise that issue of traffic density, pedestrian access and shared streets are intertwined and have been at play since the early days of automobile travel. The New York Police Department annual reports in the Municipal Library help tell the story. In 1917, Commissioner Arthur Woods submitted a report on the Department’s activities to Mayor John Purroy Mitchel. Although most reports were published annually, this one spanned the years 1914 – 1917—the duration of Mitchel’s term. Many topics in the report would sound familiar today: Bureau of Lost Property, Illicit Sale of Narcotics, Welfare Work by Policemen, Crime, Patrolmen, etc. The author, ostensibly the Police Commissioner, acknowledged that the high number of street accidents was “one of the big problems of this administration.” Citing increased population, newly-built high buildings and the use of loft buildings for manufacturing in the midst of the city as factors he noted another cause, “The invention of motor vehicles and the rapid expansion of their use, while helping to solve the transportation problem, added to the accident problem by substituting swift, silent, heavy masses for the comparatively safe horse and wagon.” Statistics compiled in precincts “showed that many more lives were lost through accident than through murder.”

New York Police Department, Bureau of Public Safety, NYC Municipal Library

The Department determined to undertake a three-pronged strategy to reduce accidents: educating the police department itself, public education and appeals to public-spirited agencies. Long before Compstat, the Department set up a data gathering and analysis project that included a special form to report accidents, pin maps to visualize the locations, and monthly meetings of a Committee of Police Inspectors on Street Safety “to which the Commanding Officers of selected precincts were called.” Attendees discussed the cause of accidents as well as how to prevent them and “awakened the Commanding Officers of the seriousness of the problem and to their responsibility in the matter.” Additionally, each precinct’s accident record was published monthly in the Police Bulletin, which every patrol office received.

NYPD Accident Report Form. NYC Municipal Reference Library

The centralized data allowed the department to identify and fix danger spots and calculate which streets were the most dangerous. It turned out that the intersection of diagonal streets/avenues with cross streets were more dangerous than rectangular crossings. Most accidents occurred mid-block and the pedestrian was “guilty of contributory negligence.” The information gleaned by analyzing the accident reports was used in lectures and Sergeants at the “training school,” a forerunner to today’s Police Academy.

Throughout 1916 and 1917, the Sergeants were deployed, in turn, to schools, clubs, community centers, and factories to educate the public on street safety. They spoke to drivers at garages and stables and prospective buyers at automobile and motorcycle shows. Patrol officers distributed Police Safety Booklets, leaflets were inserted into theater programs, stereooptican slides were shown at movie theaters and placards were placed in subways, elevated trains and street cars.

New York Police Department Annual Report,1924. NYC Municipal Library.

A committee volunteered their time to consider solutions to the accident problem. The report showed “that half the accidents are due to pedestrians trying to cross the streets at places other than the proper cross walk.” The committee concluded that persuading pedestrians to cross only at the crossings would reduce accidents. They also suggested that public education on avoiding accidents be expanded.

Police Department Commissioner Richard E. Enright seemed to take the topic of street safety and traffic congestion personally, authoring several articles as well as sections of the annual reports. In 1922, he launched the Bureau of Public Safety within the Police Department with the mission of reducing accidents and making the City’s streets safe. Staffed with police officers, analysts and communications specialists, and directed by an advertising wizard, Barron Gift Collier, who designed and launched an outreach campaign that quickly became extremely popular. It featured a cartoonish character, Aunty J. Walker who brandished a nightstick and wore an old-fashioned bonnet. She had a kind smile but a somewhat stern demeanor, urging the exercise of common sense and cautioning against carelessness.

Collier, himself was an interesting character. Born in Memphis, he built a fortune by inventing advertising cards that were posted in streetcars and trollies. His eventual holdings included several resort hotels, a cruise line to Havana and utility companies. Florida’s Collier County is named for him, perhaps because he built the Tamiami Trail across the State from the Atlantic Ocean to the Gulf of Mexico. By 1933 Collier announced he couldn’t pay his debts, and was the first filer under the bankruptcy law President Herbert Hoover signed into law on his last day in office.

New York Police Department, Bureau of Public Safety, NYC Municipal Library

The outreach and advertising campaign included posters, leaflets and pledge cards.

In 1923, the Department’s report proposed two drastic measures that resonate today: limiting the number of automobiles allowed to operate in Manhattan and making bus travel fast and efficient. Acknowledging that limiting the number of cars in Manhattan would be a heavy lift, “Nothing could be plainer than the numerous objections there would be to such a plan,” Commissioner Enright said the benefits outweighed the opposition. “The growth in the number of vehicles in the City of New York has far exceeded the capacity of the City’s streets, which were laid out at a period when the present tremendous volume of vehicular traffic could not be foreseen. There are too few main thoroughfares, while the tributary streets are too narrow to properly accommodate the vehicles using them at the present day. The cure for the trouble does not lie in further measures of regulation in congested sections. New arteries of traffic must be provided to accommodate the vast number of vehicles using the streets of the city, which may reasonably be expected to increase in numbers from year to year. Surface car tracks should be removed. The streetcar is antiquated as a means of public conveyance and constitutes an impediment to modern vehicles.” The recommendation was to replace the street cars with bus lines that provided a more flexible and expeditious means of travel with the minimum possibility of congestion.”

Actions that the Department implemented gave rise to permanent changes in the cityscape. One approach to moving traffic along was the designation of one-way streets to reduce congestion which included the placement of “street signs with arrows pointing in the direction traffic should proceed.” These one-way streets not only “moved traffic more smoothly, they are less dangerous for pedestrians, who are not confused by traffic moving in opposite directions.” Another innovation was designating safe spaces where passengers would wait to board or disembark from street cars. These Car Stop Safety Zones were placed “where groups of people usually wait for cars.” Thus, in June 1914 what have evolved to today’s bus stops were first deployed in the City as a safety measure. The City began installing traffic signals at intersections, a feature now taken for granted. One from this early period is even designated a City Landmark .

Keeping streets safe was a topic of interest in cities across the country. This was, after all, the Progressive Era in which policy was based on factfinding. Many followed the New York City example and began collecting data, establishing one-way streets and installing traffic lights. The effort was amplified by various associations including the Automobile Club of America which, in 1923, published a pamphlet entitled “Making the Road Safe.” In many ways it reads like a drivers’ training manual—speeding is reckless driving, pass only on the left-hand side after signaling, keep to the right when rounding a corner or turn, etc. But one subsection has a particularly odd tone. Dealing with pedestrians, it states that that pedestrians outnumber motorists by quite a bit and urges caution. “Even a ‘jay-walker’ cannot be run down if it can be avoided and this is true though the local rules make him an offender too. Pedestrians often appear stupid or careless, and lots of them are, but you cannot change human nature, unless by persistent education. However stupid or careless, they are human beings like yourself, and their lives are just as dear to them and to their friends and families as yours may be. It is small comfort when one kills or maims a fellow creature to say, “It was his own fault.”

This has a decidedly different tone than that of Aunty J. Walker, who urged motorists to sign a pledge to drive safely. “It’s your duty to Help Save Human Life” proclaimed a poster adorned with her image and outstretched hand.

New York Police Department, Bureau of Public Safety, NYC Municipal Library

The Police Department also stepped up enforcement, conducting inspections to identify cars with faulty breaks, monitoring traffic violations and warning jaywalkers. Whether it was the ubiquitous advertising campaign, data collection that identified areas for improvement, increased enforcement or, as is likely, a combination. The Bureau of Public Safety was successful in its mission to improve road safety. By 1925, motor vehicle injuries had dropped 77.1 % from the 1923 level. The Police Department calculated that there was a reduction of 6.2 fatalities per 10,000 vehicles operating in the City or “234 human beings were saved from death.”