We wish everyone a happy and safe Thanksgiving…

And share some archival footage from the 1968 Macy’s Parade:

Macy's Day Parade, raw footage, November 28, 1968. Recorded by Deluenthal. NYPD Photo Unit collection. NYC Municipal Archives.

We wish everyone a happy and safe Thanksgiving…

And share some archival footage from the 1968 Macy’s Parade:

Macy's Day Parade, raw footage, November 28, 1968. Recorded by Deluenthal. NYPD Photo Unit collection. NYC Municipal Archives.

Five hundred years ago, in a mission to find the Northwest Passage to Asia, Florentine explorer Giovanni da Verrazano sailed along the northeastern coast of North America. He voyaged from present day North Carolina, to Nova Scotia, and became the first European known to have sailed into New York Harbor.

Aerial View Of Verrazano-Narrows Bridge with construction almost completed, from Brooklyn looking toward Staten Island, ca. 1964. Department of Ports & Trade photograph collection. NYC Municipal Archives.

More recently, on November 21, 1964, the Verrazano-Narrow Bridge, named in honor of the explorer, opened to traffic. New Yorkers like to describe features of their city as the tallest, the biggest, etc., but the Verrazano bridge is truly the embodiment of superlatives. The 693-foot towers are so tall that they are 1-5/8 inches farther apart at the top than the bottom because the 4,260-foot distance between them made it necessary to take the earth’s curvature into account. When completed in 1964 it was longest suspension bridge in the world. There is enough steel in the structure to build three Empire State Buildings. The wire in the four main cables would encircle the earth nearly six times.

Aerial View Of Verrazano-Narrows Bridge with construction almost completed, from Brooklyn looking toward Staten Island, ca. 1964. Department of Ports & Trade photograph collection. NYC Municipal Archives.

Researchers will learn these facts, and many more, from resources in the Municipal Library. The vertical files, for example, contain an eclectic assortment of source materials. One such item, the Winter 2001-2002 edition of From the Archive, a publication of MTA Bridges and Tunnels, is especially informative and includes numerous historical photographs documenting construction of the bridge. According to the narrative, New York State authorized construction of a bridge across the narrows between Staten Island and Brooklyn in 1946. Nine years later, the Triborough Bridge and Tunnel Authority (TBTA), together with the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, announced a proposal to build a 12-lane double deck suspension bridge. Ground was broken on August 13, 1959, and the $320 million structure opened to traffic on November 21, 1964.

Aerial View Of Verrazano-Narrows Bridge with construction almost completed, from Brooklyn looking toward Staten Island, ca. 1964. Department of Ports & Trade photograph collection. NYC Municipal Archives.

It should come as no surprise that master builder Robert Moses played a significant role in planning and construction of the bridge. As Chairman of the TBTA (now MTA Bridges and Tunnels), Moses saw the Verrazano as the last of the suspension bridges needed to complete his web of arterial highways connecting the five Boroughs with each other and the mainland.

Verrazano-Narrows Bridge Cable Spinning, March 7, 1963. Triborough, Bridge and Tunnel Authority. NYC Municipal Library.

Chart, Verrazano-Narrows Bridge Cable Spinning, March 7, 1963. Triborough, Bridge and Tunnel Authority. NYC Municipal Library

The vertical file contains a small pamphlet titled, “Remarks of Robert Moses . . . at the Cable Spinning Ceremony at the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge Thursday, March 7, 1964.” In a short speech transcribed in the pamphlet, Moses said of the bridge, “You see here the buckle in the chain of metropolitan arterials devised and approved by federal, state and local agencies, departments and officials too numerous to mention individually, a framework of bypasses and through routes of the most modern design which still requires years to finish.” In a not very subtle allusion to the considerable opposition voiced by residents of Bay Ridge, Brooklyn, whose homes were demolished to make way for the bridge, Moses went on to say, “The obstacles in our way become more formidable, the opposition more vociferous, the support less steady and certain, the courage or, if you please, obstinacy of those in charge less durable and the cost immeasurably greater as time goes on.”

Aerial view of the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge. Photo taken from a helicopter, July 15, 1965. HPD Collection. NYC Municipal Archives.

Moses persevered, as he did, and the bridge was completed just a few months later. According to clippings from the Staten Island Advance, “The day dawned blustery and cold, but no dampers were put on the spirit of the Verrazano-Narrows bridge opening...” (November 23, 1964.) Other Advance stories reported how the cold weather discouraged politicians from making long-winded speeches. Spectators cheered Governor Nelson Rockefeller’s announcement that “I think I’ll file my speech for the record.”

Aerial view of the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge. Photo taken from a helicopter, July 15, 1965. HPD Collection. NYC Municipal Archives.

The Story of the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge. Triborough, Bridge and Tunnel Authority. NYC Municipal Library.

Reading through the chronologically arranged vertical file, an article dated March 3, 1962, from the World-Telegram, hints at stories that would dominate later coverage: “Staten Island: Goodbye to a Way of Life—Verrazano Bridge, Now Building, Will Double Population, End Rural Refuge.” Indeed, clippings from 1984, on the occasion of the bridge’s twentieth anniversary, echo the earlier prediction: “The Bridge took a toll on the Island’s mores,” headlined the Advance on November 18, 1984.

During the 1980s and 90s, stories about the bridge tolls proliferate in the clipping files. On June 22, 1983, The New York Times reported “New Law Gives S.I. Drivers a 25-cent Discount on Verrazano.” And beginning in 1970, thanks to the annual New York marathon that kicks off on the Verrazano Bridge on the first Sunday in November, the great suspension bridge always receives lots of media attention.

Verrazano Bridge - Aerial, March 29, 1966. Department of Ports and Trade photograph collection. NYC Municipal Archives.

Giovanni da Verrazzano, The Discoverer of New York Bay, 1964. NYC Municipal Library.

Searching Municipal Library shelves revealed an illustrated pamphlet, Giovanni da Verrazzano, The Discoverer of New York Bay. Published in 1964, on the occasion of the inauguration of the bridge, it chronicles the life and history of the explorer. According to the introduction, “Here we wish to . . . help awaken interest in the daring, adventurous nobleman who gave New York its very first name of Angouleme, recorded its exact position on a map, and opened the path to the other voyagers who have come to these shores in ever-growing numbers from then on. Meet Giovanni da Verrazzano, the discoverer of New York Bay!” What the pamphlet apparently fails to mention is that he is believed to have been eaten by cannibals in the West Indies, according to the Encyclopedia of New York City. But there is a bronze statue of Verrazano in Battery Park and a beautiful suspension bridge to remind New Yorkers of his place in our history.

Question 1:

Infamous NYC Parks Commissioner Robert Moses left an indelible mark upon the landscape of NYC including each of the following projects except:

1964 World’s Fair

Queensboro Bridge

Gowanus Expressway

Lincoln Center

Question 2:

Designed by Central Park architects Olmsted & Vaux, 10,000 cyclists took to the road for the 1896 opening of the nation's first bike lane on this Brooklyn thoroughfare. What was this thoroughfare:

Ocean Avenue

Eastern Parkway

Ocean Parkway

Bedford Avenue

Commissioner Pauline Toole welcomed trivia players to the Surrogate’s Court atrium. Trivia Night at the Archives, November 14, 2024. NYC Municipal Archives.

Chilly outdoor temperatures yesterday evening did not deter more than 90 trivia fans at DORIS’ first Trivia Night. Held in the grand atrium at the Surrogate’s Court building at 31 Chambers Street, the event tested participants’ knowledge of New York City-related trivia. Mr. Austin Rogers, a twelve-time Jeopardy champion presided over the fun evening. Rogers developed a program that enables multiple players to participate in-person or virtually. His app also tracked responses in real time, automatically calculating each team or individual players’ point total.

Austin Rogers mc’d the program. Trivia Night at the Archives, November14, 2024. NYC Municipal Archives.

City archivists Cynthia Brenwall and Katie Ehrlich developed fifty questions based on their knowledge of City history and Municipal Archives collections. The categories included sports and the City, the City in film and screen, and Name that Borough!

Rogers called out the multiple-choice questions. Participants simultaneously viewed the questions on monitors in the atrium, and on their phones or other devices. With up to sixty seconds to deliberate, participants clicked on their responses.

Deliberating the correct answer. Trivia Night at the Archives, November 14, 2024. NYC Municipal Archives.

Between trivia rounds, guests were treated to video clips of music performances from the Municipal Archives’ digital collection. Selections included Duke Ellington and his band performing at City Hall in 1969, Ray Santos and his orchestra “The Caribbean Music Experience” on WNYC-TV in 1995, performances by Princess Nokia and Sweet Honey in the Rock at Declaration of Sentiments: The Remix in 2015, and more.

And the winner is....

After fifty questions, challenging for even the most informed New Yorker, the audience cheered the winning team, “Naka.” The team “Flatlanders” took second place. “The Pizza Rats” took the honors for “Cool Team Name Winner.”

“Naka,” the winning team stands to accept cheers from the audience. Trivia Night at the Archives, November 14, 2024. NYC Municipal Archives.

Question 3.

Which of the following is not in the time capsule installed in 1870 beneath the base of The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s outdoor installation of the obelisk popularly known as “Cleopatra's Needle?”

Complete Works of Shakespeare

Declaration of Independence

1870 NYC Census

Portrait of George Washington

Question 4.

This Brooklyn-born blonde bombshell spent time in the Blackwell’s Island Penitentiary for obscenity charges stemming from her 1927 play “Sex.”

Fay Wray

Mae West

Greta Garbo

Clara Bow

Okay, here are the answers. Question 1. - Queensboro Bridge; Question 2. - Ocean Parkway; Question 3. Portrait of George Washington; Question 4. - Mae West.

How did you do? Ready to join us for the next Trivia Night at the Archives? Stay tuned: it will be in the spring!

Earlier this week, the Department of Records and Information Services (DORIS) launched an interactive map, accessible on both desktop and mobile devices, to help people connect with the stories behind nearly 2,500 co-named streets, intersections, parks and other locations throughout the City.

NYC Honorary Street Names Map. Department of Records and Information Services, 2024.

Perhaps you’ve seen the markers. They are usually attached to a signpost just beneath the street name. For example, a sign at the corner of Park Row and Spruce Street in Manhattan informs us that it is co-named “Elizabeth Jennings Way.” By clicking that location on the map you will learn that the City Council designated Park Row between Beekman and Spruce Streets in honor of Jennings, a Black teacher who integrated the City’s trolleys in 1854 by refusing to “get off” when instructed.

Just a block away, at the northeast intersection of Park Row and Beekman Street, a sign says it is also known as Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton Corner. Map users will find out that in 2004 the Council honored the two women’s suffrage pioneers for their contributions to gender equality.

Street Sign, Susan B. Anthony & Elizabeth Cady Stanton Corner, 2024.

The origins of the map initiative date to 2023 when the New York City Council passed legislation sponsored by Councilmember Gale Brewer mandating online access to biographical and/or background information about persons or entities honored by the Council with a co-named street, intersection, park, or playground.

Mayor Eric Adams designated DORIS as the agency responsible for posting co-named street information on its website. Initially, DORIS published the City Council local laws containing the information online in the Government Publications Portal. To make the co-named street data more accessible, the agency’s application developers and interns created an interactive map that people walking around the city can access on their phones.

Street Sign, Elizabeth Jennings Place, 2024.

Using mapping software from the Office of Technology and Innovation (OTI), DORIS’ application developers built the map. They created a form to enter the biographical or background information contained in local laws termed “street renaming bills” that have been passed by the City Council between 2001 and the present. The data on the form is linked to the appropriate location on the map. During the summer of 2024, a team of interns from CUNY and the PENCIL programs transferred the data about locations and each of the 2,496 individuals into the form.

The map is searchable by the name of the individual, zip code, and categories such as “firefighter” or “police officer.” So far, there are 1,610 co-named intersections, and 886 co-named streets.

Residents of the Astoria neighborhood in Queens are not likely to be surprised by the co-named Tony Bennett Place at the intersection of 32nd Street and Ditmars Boulevard. The co-naming by the Council in 2024 honored Astoria-native Bennett for his lifetime in music that included 20 Grammy Awards, and more than 50 million records sold worldwide.

NYC Honorary Street Names Map, Lieutenant Theodore Leoutsakos Way, Astoria, Queens. Department of Records and Information Services, 2024.

Not all co-named streets honor famous people. For example, there is Lieutenant Theodore Leoutsakos Way, just two blocks away from Tony Bennett Place, at the intersection of 29th Street and 21st Avenue in Astoria. In 2016, the Council honored Lt. Leoutsakos for his service as a first responder during the 9/11 terrorist attacks at the World Trade Center. A United States Air Force Veteran who served during the Vietnam War, Leoutsakos was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer as a result of his time spent at Ground Zero. The diagnosis came shortly after he retired from 24 years as a New York State Court Officer.

In 2002 and 2003, local laws enacted by the City Council included co-named streets for more than 400 first responders killed on 9/11. Many of those streets lack biographical information. DORIS is working with the Council to gather the biographical information for inclusion in upcoming local laws. The information will subsequently be added to the map.

NYC Honorary Street Names Map, Tillie Tarantino Way, Williamsburg, Brooklyn. Department of Records and Information Services, 2024.

In the event that you detect an error in the biographical information, contact your local City Councilmember. Changes to the information on the map will be made after the Council includes the correction in a new street renaming law.

If a sign with the name of the co-named street is missing from its designated location, go to nyc.gov/311 or call 311 to report it.

DORIS will continue to add data to the online map, using the information in local laws pre-dating 2001.

At the launch of the map, Councilmember Gale Brewer remarked that “Our City’s history is long and deep, and we need tools to remember those who came before us—whether their name is on a building or on a street sign—and why they’re being honored. Think of this as Wikipedia for street names!”

Baseball fans know that the Yankees v. Dodgers games this week were not the first time the two faced off in the World Series. In 1941, the Yankees vanquished the Dodgers four games to one. At their next meeting in 1947, the Yankees won again, four games to three. The two teams dueled ten more times, most recently in 1981, when the Dodgers won the trophy four games to two.

Double Header, April 14, 1943, Poster. Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia Collection. NYC Municipal Archives.

Perhaps less well-remembered is a pre-season tournament with the Yankees, Dodgers and Giants. It took place on April 15, 1943, as a benefit for the Civilian Defense Volunteer Office. At that time all three teams were New York-based—the Yankees in The Bronx, the Giants at the Polo Grounds in Manhattan, and the Dodgers at Ebbets Field, Brooklyn. In the benefit match, the Yankees battled the Dodgers in the first game; the Giants played the winner in the second.

President Roosevelt established the Office of Civilian Defense on May 21, 1941, and appointed Mayor LaGuardia as its National Director. LaGuardia held this position until the end of World War II. The Office was tasked with alerting and educating the public about civilian defense, organizing volunteer groups, and training fire protection and bomb disposal units in anticipation of damage caused by air raids.

Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia’s records provide context for the benefit tournament. His collection is organized into twenty-one series such as departmental, general and subject files. In addition, there are two series, the Office of Civilian Defense (OCD), and the related Office of Civilian Defense Volunteer Office (CDVO), relevant to research on the topic.

The OCD series includes a folder of documents concerning the benefit game. One informative item is a draft statement from the Mayor appealing to all New Yorkers to support the CDVO by buying tickets to the baseball series to be played at Yankee Stadium starting at one p.m. on April 15, 1943 The statement quotes LaGuardia: “CDVO is doing a great job... and deserves the support of every New Yorker. Men and women volunteers are giving freely of their time and energies in undertaking the many home-front tasks occasioned by the war. CDVO up to now has been run on voluntary contributions but money is needed urgently to carry on the work.”

The folder also contains carbon copies of letters LaGuardia sent to heads of City agencies requesting the release of designated employees to help with ticket sales. The only blip in the preparations appears to have been in the New York City Housing Authority. A telegram to the Mayor from “Painters NYC HA,” dated April 13, just two days before the tournament explained the situation: “Please be informed that painters of NYC Housing Authority have been refused permission to attend baseball game April 15 while office force of same authority have been granted same permission. Strongly protest this flagrant discrimination.” The next day, April 14, LaGuardia received a letter from Edmond Borgia Butler, Chairman of the New York Housing Authority: “As you know, our painters and other maintenance employees work on a rigid schedule, which must be maintained if the necessary services are to be supplied tenants in our projects. Except for these employees and the administrative staff, all other employees were permitted to be absent to attend the baseball.”

Telegram, April 13, 1943. Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia Collection. NYC Municipal Archives

The file does not include LaGuardia’s response to these missives.

Whether or not Housing Authority painters attended the game may never be known, but 35,301 spectators did witness the tournament, according to the New York Times. The Times story related how the Brooklyn team vanquished the Yankees, six to one, and then went on to defeat the Giants, one to zero. In the words of Times reporter John Drebinger: “In an era of considerable scarcity the Dodgers simply had too much of everything yesterday as they crowned themselves the so-called “mythical” baseball champions of Greater New York by polishing off both the Yankees and Giants in the CDVO double-header at the Stadium before a gathering of 35,301 frostbitten but highly enthusiastic onlookers.”

In his statement Mayor LaGuardia added “The Presidents of the Yankees, Dodgers, and Giants ball-clubs have generously donated the net proceeds of these two games to CDVO and it is up to all of us to make April 14th the greatest day in baseball history.”

Municipal archivists processing records in the Manhattan Building Plans collection recently discovered blueprints submitted to the Department of Buildings in 1929 for construction of the Empire State Building. Completion of the iconic building in 1931 capped a mad race to build the tallest skyscraper in the world, and Municipal Archives collections help tell the story.

Empire State Building, 5th Avenue Elevation. Dept. of Buildings Plans, NYC Municipal Archives.

Woolworth Building from 27th floor of Municipal Building (short focus), October 22, 1914. Eugene de Salignac, photographer. Dept. of Bridges/Plant & Structures Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

Just as the stock market soared to new heights in the 1920s, so too did the height of the skyscraper. The race to construct the tallest building in the world that began in the second half of the decade, was not the first in New York City history. In 1908, the Metropolitan Life Insurance tower on Madison Square outdistanced the Singer Building, completed only eighteen months earlier. The 1913 Woolworth Building eclipsed both, rising 692 feet into the sky.

The 1916 New York Zoning ordinance, World War I, and a post-war recession halted further competition for nearly a decade. By the 1920s, amidst rising prosperity, and in an age that extolled record-breaking builders sought to surpass the “Cathedral of Commerce.”

The headline on the front page of The New York Times on June 25, 1925, signaled resumption of the race for the tallest structure: “42-Story Office Building... To Go Up In West 42nd St.” The story added that real estate speculator John Larkin declared his building would be the tallest structure in New York north of the Metropolitan tower, “and the largest building operation ever undertaken near the Times Square section.”

Just three months later, on September 1, 1925, the Times front page announced another super-tall building: “65-Story Hotel Here to be Part Church.” The tower, planned as part church and part hotel, would rise in upper Manhattan, on Broadway, between 122nd and 123rd Streets. Clearly designed to best the Woolworth Building it would exceed the lower Broadway structure by only 8 feet. The building developer, Oscar E. Konkle, President of Realty-Sureties, Inc. planned the unusual church-hotel combination to express his gratitude for the life of his son, who had miraculously recovered from a nearly fatal disease. Konkle announced that ten percent of the profits would be devoted to missionary work and that none of the occupants of the hotel would be permitted “to smoke or use tobacco, or drink intoxicants on the premises, from which it [was] also announced, Sunday newspapers may be eliminated.”

Lower Manhattan Skyscrapers, 1937. James Suydam, photographer. WPA Federal Writers’ Project Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

Perhaps needless to say, this noble edifice was not built. In a follow-up story, on June 14, 1926, the Times reported: “Possibly the promoter has despaired of finding... New Yorkers willing to do without Sunday newspapers and pledging themselves to abstain even from solitaire in the privacy of their own chambers.”

Chrysler building under construction, 1930. FDNY Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

Larkin’s building also failed to materialize, but in September 1926, he announced plans for a gargantuan 110-story building on his 42nd Street plot. His comments concerning this behemoth were revealing: “It has been asked of us why we chose to design this building taller than other buildings... but we did not set out to accomplish this specific result. We simply endeavored to provide the greatest amount of permanent light and air to the greatest possible proportion of floor area with a surplus of elevator service. The projected building came naturally out of these conditions.” (New York Times, December 5, 1926.)

Whether economics “naturally” dictated a 110-story building is debatable; in any case, Larkin’s tower, like the Konkle Church on Morningside Heights only existed in the imaginations of their builders. Woolworth’s monument remained secure in its position as highest in the world. Nevertheless, it was clear that the race was on in earnest.

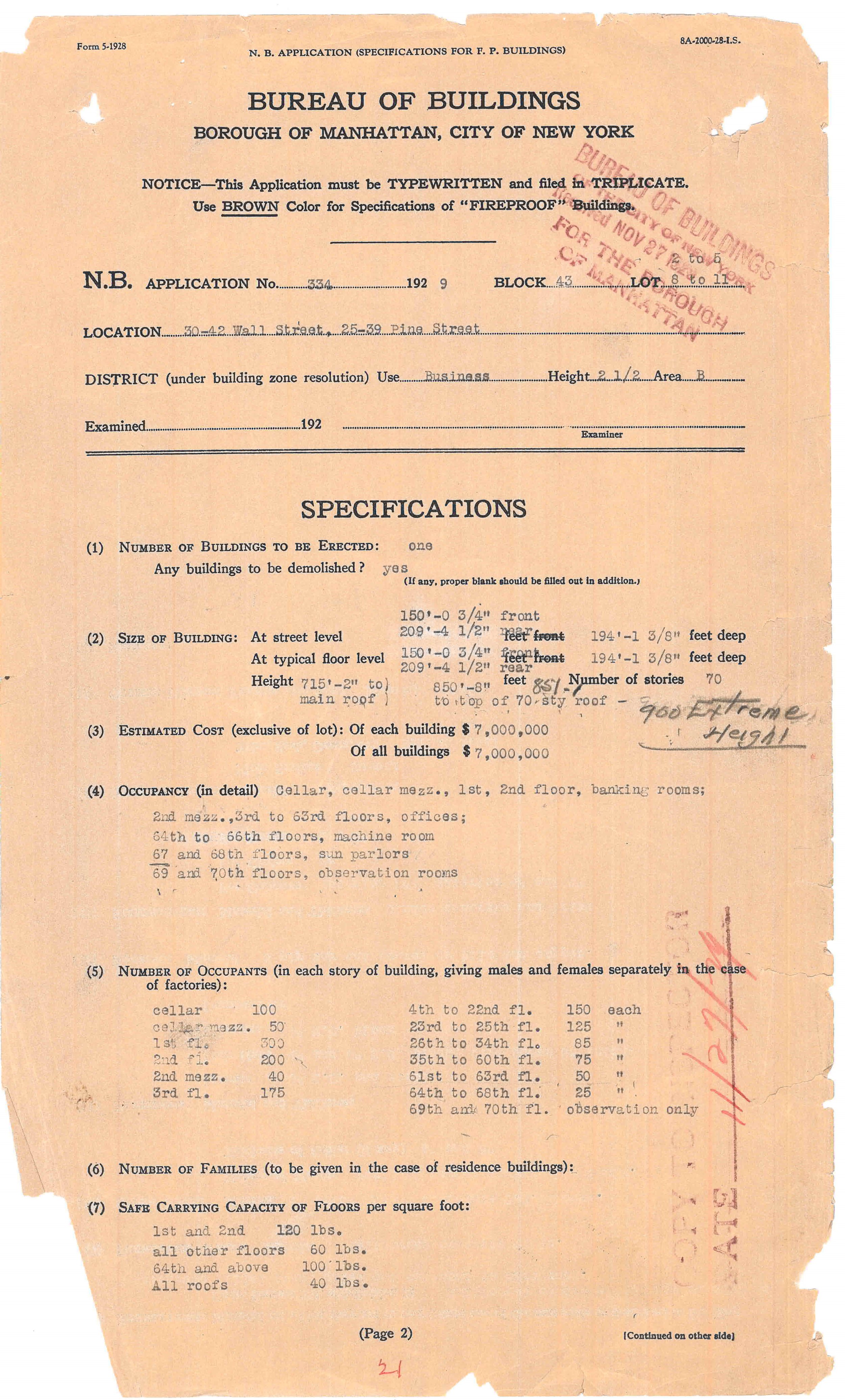

Bank of Manhattan, New Building Application, 30-42 Wall Street, 1929. Dept. of Buildings Manhattan Permit Collection.

On February 16, 1928, former Senator William H. Reynolds, President of the Reylex Corporation, filed plans with the Department of Buildings for a 63-story building on Lexington Avenue at 42nd Street that would ascend to a height of 755 feet, about 40 feet less than the Woolworth building. A few days later Reynolds filed revised plans with the Buildings Department that stretched the skyscraper 53 feet to make it 808 feet tall, 16 feet higher than Woolworth. Before construction began, however, in October 1928, Reynolds sold his leasehold to automobile mogul Walter Chrysler. (New York Times, February 2, 8; October 17, 1928.)

In 1929, a new headquarters for the Bank of Manhattan Company on Wall Street loomed as another potential contestant in the skyscraper sweepstakes. According to the New Building application specifications on file in the Archives’ Manhattan Building Permits collection, it would be a 564 foot, 47-story tower. Revised plans submitted in April 1929, stated the building would be 60-stories and 715 feet high; still less than Chrysler’s 42nd Street tower.

The race was far from over. The next actor in this drama was Alfred E. Smith, the former Governor of New York State and unsuccessful presidential candidate. Again, the front page of the Times carried the announcement: “Smith to Help Building Highest Skyscraper.” The story explained that Smith would be President of a company that would build the highest office tower in the world on the site of the Waldorf Astoria Hotel, at 5th Avenue and 34th Street. (August 30, 1929.)

Empire State Building, 33rd and 34th Street Elevations, Sub-basement to 39th floor. Dept. of Buildings Plans, NYC Municipal Archives.

According to the entry in the Archives’ Building Department docket book collection, the developers filed plans on January 22, 1929, for a 55-floor skyscraper. By August the height had been increased to 60-stories. Although Smith denied that the plans were altered so that the building, later named the Empire State Building, would be tallest in the world, his denial seems unpersuasive in view of the circumstances. (New York Times, August 30, 1929.)

National City Bank-Farmers Trust Company building, New Building Application, 1930. Dept. of Buildings Manhattan Permit Collection.

In October of 1929, just as the stock market began to falter, two more giant skyscrapers entered the race. First, the National City Bank-Farmers Trust Company filed plans with the Buildings Department for a 66-floor tower that would climb 845 feet in Manhattan’s financial district, higher than both the Chrysler and Bank of Manhattan buildings. Two days later, A. B. Lefcourt announced that he would construct a 1,050 foot tower in Times Square which would push up 50 feet higher than the Empire State Building. (New York Times December 18,1929.)

Both these structures became early casualties of the Stock Market crash. The Lefcourt tower never progressed further than the front page announcement in the Times. The National City Bank building was constructed, but significantly reduced in scale. Nevertheless, both skyscrapers were a potential threat in the race and spurred the finalists on to even greater heights.

By late 1929, the Chrysler Building reached 861 feet high. Believing that to be the final height, the Bank of Manhattan altered their plans by adding a “sun parlor” and observation rooms capped with a lantern sporting a flagpole that increased its height to 925 feet. Bank builder, Paul Starrett, President of Starrett Brothers, Inc., denied that the plans had been altered, saying his company “was not competing for height supremacy in building.” (New York Times October 20, 1929.) But specifications on file in the Permits collection indicate that they were indeed amended.

Night View Midtown Manhattan, shows the Chrysler and Empire State, ca. 1937. WPA Federal Writers’ Project Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

When Walter Chrysler and his architect William Van Alen realized that the Bank of Manhattan Company tower would exceed their building in height, they conceived the idea of secretly constructing a “supplemental vertex” (actually a modernistic flagpole) inside the fire tower, and when completed, lifting it to the crown of the building. The result was that the Chrysler tower secured the coveted title of tallest structure in the world. (New York Times, February 9, 1930).

Empire State Building, Elevations of Observation Tower. Dept. of Buildings Plans, NYC Municipal Archives.

Empire State Building observation tower, 1941. WPA Federal Writers’ Project Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

Their victory was short-lived, however. The surprise addition to the Chrysler tower prompted the Empire State group to add a “dirigible mooring mast” to the top of their building. It is debatable whether the mooring mast could have ever been practicable, but it made the building 1,300 feet tall, safely taller than all rivals. Two unsuccessful attempts to anchor dirigibles were made after the building opened, but it became much more profitable as an observation deck. (New York Times, July 21, 1930.)

And so the race ended. But who had won? The Empire State Building, soon to be known as the “Empty State Building,” was not fully rented until after World War II.

The story does not end here. The skyscraper would rise again to even greater heights within a half century. Perhaps a New York Times article from January 22, 1925, about skyscrapers perhaps best explains their continuing attraction:

“[There is] a new witchery in these pinnacles bathed in sunset light, a sort of urban alpine glow; ...a new mystery of crepuscular canyon streets, haunted by darkling throngs.”

Invitation for opening of Empire State Building from former Governor Alfred E. Smith to his friend “Jim” aka Mayor James J. Walker. Mayor Walker Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.